An astonishing statement has been released by ex-ECB members, who condemn the European Central Bank’s approach to monetary policy.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

An astonishing statement has been released by ex-ECB members, who condemn the European Central Bank’s approach to monetary policy.

On 12 September, the European Central Bank (ECB) announced that it will introduce a two-tier system for banks’ reserve remuneration, exempting a portion of deposits in excess of the minimum reserve requirement from the negative deposit facility rate and giving that portion a 0% rate instead. The introduction of the tiering system on banks’ excess liquidity placed at the central bank is credit positive, says Moody’s.

This is because it will reduce the cost of holding liquidity at the ECB, providing a partial offset. They expect that the tiering mechanism will be particularly positive for banks with material excess liquidity.

The announcement comes as the ECB’s Governing Council announced that it would maintain its accommodative monetary policy stance given slowing economic conditions in Europe, persistent downside risks of global trade tensions and muted inflationary pressures. As a result, the ECB relaunched its Asset Purchase Programme and lowered the rate on the deposit facility by 10 basis points to negative 0.50% from negative 0.40%.

The tiering system on banks’ excess liquidity will moderate the negative effect of persistent low rates on banks in the euro area.

The two-tier system will exempt from negative interest a maximum volume of six times the banks’ minimum reserve requirement, therefore paid at 0%. The minimum reserve requirement and the non-exempted portion of the excess reserves will be charged 0.5%.

The tiering system will apply to all banks and start at the end of October 2019.

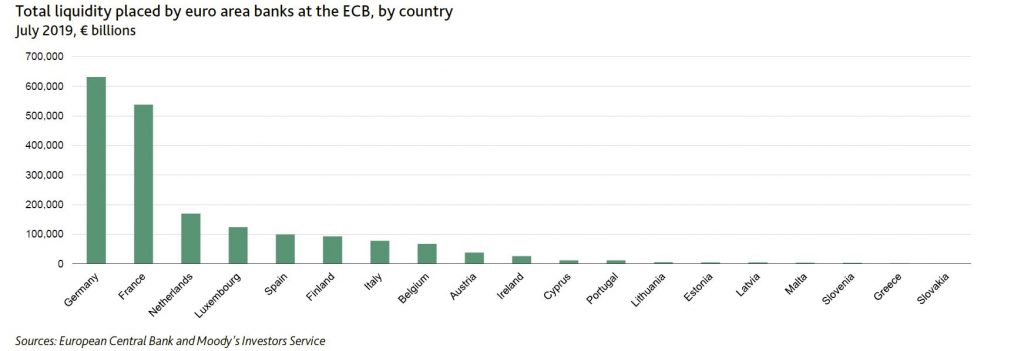

Since the aggregated minimum reserve requirement is currently €132 billion, approximately €786 billion (six times the aggregated minimum requirement) would be exempt from negative rates. The remaining reserves and deposit facility would be subject to the new deposit rate of negative 50 basis points, providing a net annual benefit to the euro area’s banks of about €2 billion relative to the status quo of negative 40 basis points on the full balance of €1.9 trillion liquidity placed at the ECB, equivalent to 0.8% of EU banks’ annual net interest income.

In 2018, Moody’s estimate that banks’ €1.8 trillion of total liquidity placed at the central bank at a rate of negative 0.40% cost around €7 billion. This compares with US banks, whose deposits placed with the US Federal Reserve in 2018, remunerated at a rate of 2.35%, represented a revenue of around €40 billion.

The introduction of a two-tier system for banks’ reserve remuneration will be particularly positive for German and French banks, whose liquidity holdings exceed the most their reserve requirements and account for more than 60% of the total liquidity placed at the ECB. The tiering mechanism that the ECB has introduced is similar to the mechanism implemented by Switzerland’s central bank, which also set exemption thresholds for deposit rates as a multiple of banks’ minimum reserve requirements.

Southern European banks will benefit to a lesser extent because they do not hold large amounts of excess reserves at central banks.

However, they will continue benefiting from the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III). The ECB in June 2019 announced that banks could access two years of funding at 10 basis points above the ECB’s refinancing rate of 0%. On 12 September, the ECB removed the 10-basis-point surcharge and announced that TLTRO funding would extend to maturities of three years instead of two, conditions that will be particularly favourable for banking systems with large outstanding repayments from previous TLTRO programmes, such as those in Italy and Spain.

On 19 March, the Haut Conseil de la Stabilité Financière (HCSF), the French macroprudential authority, announced it would increase banks’ countercyclical capital buffer on their exposures to French counterparties to 0.50% from 0.25% by no later than 2 April 2020.

The increase, the first since the HCSF established the buffer in June 2018 to stem the potential for excessive credit growth, raises banks’ capital requirements, a credit positive, says Moody’s.

The countercyclical capital buffer was introduced with Articles 136-140 of the European Union’s (EU) Capital Requirement Directive IV (CRD IV) to build up extra capital in boom periods and pre-empt the credit risks that accumulate during economic upswings. The buffer applies to all French, EU and European economic area banks’ that have exposures to French counterparties.

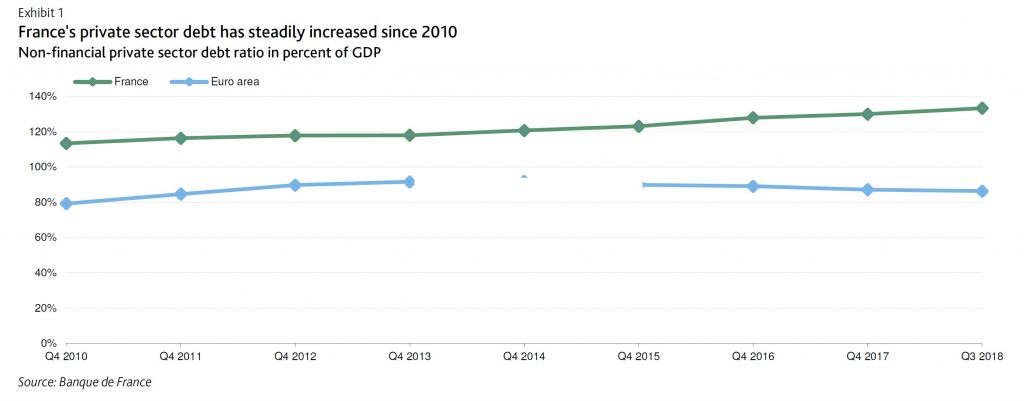

Last Monday’s increase aims to dampen continuing credit growth : non-financial private sector debt increased to 133.3% of GDP as of third-quarter 2018 (one of the highest levels in the EU) from 131.0% as of first-quarter 2018 and 113.4% at year-end 2010.

Since 2016 credit to corporates and households has increased at a 4%-6% annual rate amid relaxed lending standards (especially on housing loans with higher loan-to-value ratios and longer maturities), rising house prices and increasing leveraged buyout transactions (up 3.6% in February 2019 compared to February 2018). Moreover corporate debt issuance also drove the increase in indebtedness, in particular at large corporates, which prompted the HCSF to express some concern.

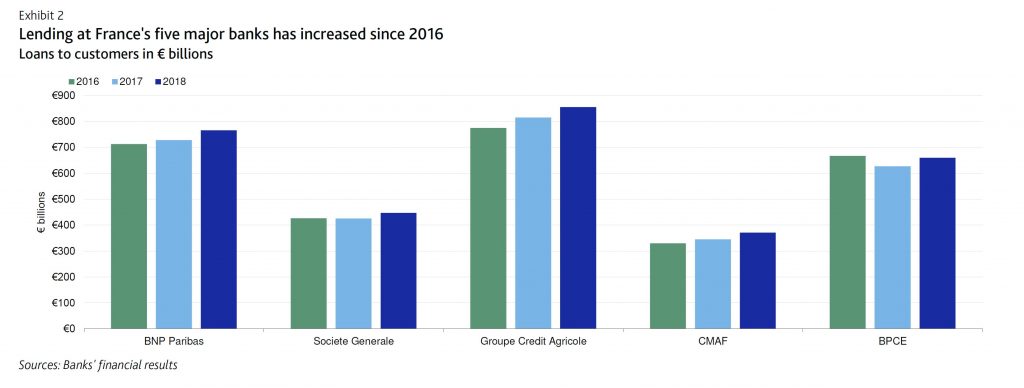

Total lending (domestic and international) among France’s five major banks – BNP Paribas, Societe Generale, Credit Agricole S.A., Banque Federative du Credit Mutuel, BPCE – grew 5.6% year over year as of year-end 2018, with bank loans to SMEs growing a robust +6.3% for the same period.

Additionally, France’s credit-to-GDP gap (measuring the difference between the credit-to-GDP ratio and its long-term trend) was 2.7 percentage points in fourth-quarter 2018, versus the euro area average of negative 12.4 percentage points at the same time.

The HCSF’s decision will be submitted to the ECB on a non-objection basis and will be adopted before 2 April 2019 for an effective implementation of this requirement a year later (April 2020).

The 2018 decision to set a CCyB at 0.25 % has not resulted in a more moderate lending growth at French banks hence the decision to tighten it at 0.50%. It remains to be seen whether or not a higher capital add-on will be successful in materially curbing lending at banks. If not successful the official sector may consider tightening the 0.5 % CCyB once again.

We assign a one-notch downward adjustment for credit conditions in France’s macro profile, which reflects the macro- risks faced by banks, to account for the material growth of private sector indebtedness in France since 2015 and the risk that a too rapid rise in corporate and household debt could eventually increase the vulnerability of borrowers to an economic downturn.

Many European have imposed much higher countercyclical capital buffers, up to 2.5% (for example, Sweden). The growing use of CCyBs in European countries – 11 countries have resorted to this prudential measure – points to a potential accumulation of excessive credit risk throughout the region.

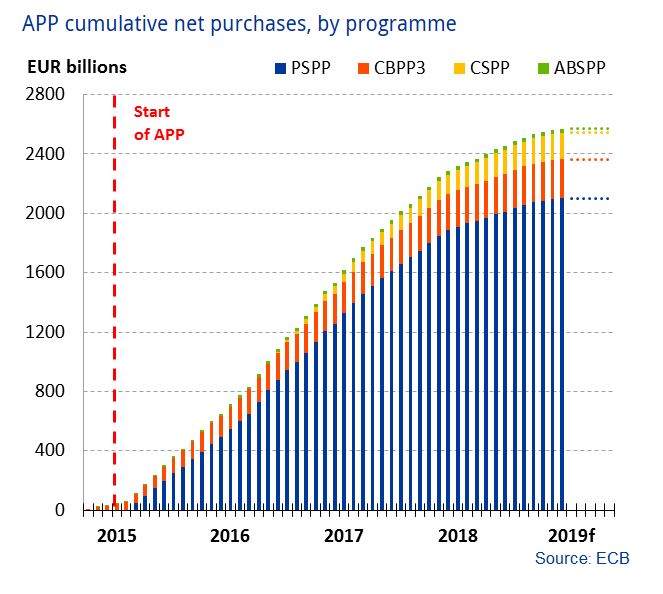

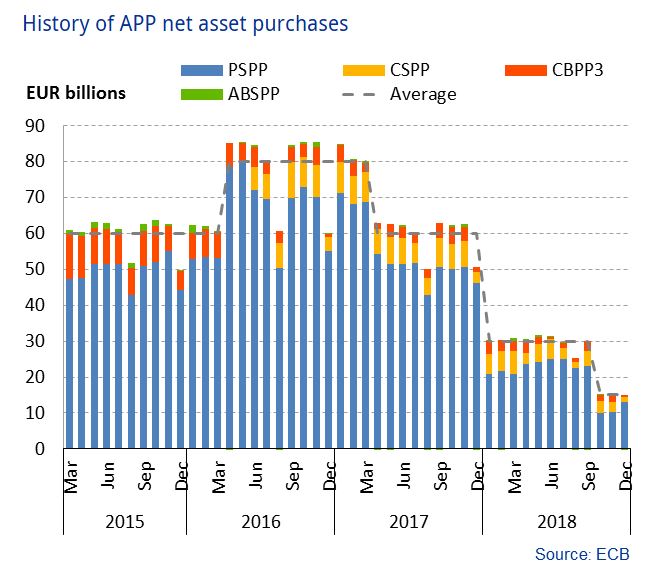

The European Central Bank has been running an aggressive asset purchase programme their expanded asset purchase programme (APP). The period of APP net asset purchases ended in December 2018. The question is now, what will the impact be, given the fact this programme has been supporting the euro economies for the past three years.

The APP includes all purchase programmes under which private sector securities and public sector securities are purchased to address the risks of a too prolonged period of low inflation over the medium term. The measures help to further strengthen the pass-through of the Eurosystem’s asset purchases to financing conditions of the real economy, and, in conjunction with the other non-standard monetary policy measures in place, provides further monetary policy accommodation.

On 13 December 2018, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) decided to end the net purchases under the APP in December 2018 and announced that it “intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation”.

However, the Governing Council will aim to maintain the size of its cumulative net purchases under each constituent programme of the APP at their respective levels as at the end of December 2018. Limited temporary deviations in the overall size and composition of the APP may occur during the reinvestment phase due to operational reasons.

Within the programme there are currently four elements.

Corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP)

Between 8 June 2016 and 19 December 2018 the Eurosystem conducted net purchases of corporate sector bonds under the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP). As of January 2019, the Eurosystem no longer conducts net purchases, but continues to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities held in the CSPP portfolio.

Public sector purchase programme (PSPP)

Between 9 March 2015 and 19 December 2018 the Eurosystem conducted net purchases of public sector securities under the public sector purchase programme (PSPP). As of January 2019, the Eurosystem no longer conducts net purchases, but continues to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities held in the PSPP portfolio.

The securities covered by the PSPP include nominal and inflation-linked central government bonds and bonds issued by recognised agencies, regional and local governments, international organisations and multilateral development banks located in the euro area

As of December 2018, government bonds and recognised agencies make up around 90% of the total Eurosystem portfolio, while securities issued by international organisations and multilateral development banks account for around 10%. These proportions will be maintained, on average, during the reinvestment phase.

Asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP)

Between 21 November 2014 and 19 December 2018 the Eurosystem conducted net purchases of asset-backed securities under the asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP). As of January 2019, the Eurosystem no longer conducts net purchases, but continues to reinvest redemptions from securities held in the ABSPP portfolio.

The reinvestment of ABSPP redemptions are distributed over time and in line with market issuance and secondary market liquidity. The ABSPP reinvestment purchases are conducted in a highly flexible manner in primary and secondary markets across jurisdictions.

The ongoing presence of the Eurosystem in the ABS market supports the diversification of funding sources and stimulates the issuance of new securities. The ABSPP therefore further enhances the transmission of monetary policy, facilitates the provision of credit to the euro area economy, eases borrowing conditions for households and firms and contributes to a sustained adjustment of inflation rates to levels that are below, but close to, 2% over the medium term.

Covered bond purchase programme 3 (CBPP3)

Between 20 October 2014 and 19 December 2018 the Eurosystem conducted net purchases of covered bonds under a third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3). As of January 2019, the Eurosystem no longer conducts net purchases, but continues to reinvest the principal payments from maturing securities held in the CBPP3 portfolio.

The measure helps to enhance the functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism, supports financing conditions in the euro area, facilitates credit provision to the real economy and generates positive spillovers to other markets.

The European Central Bank (ECB) delivered on its promise. While it kept interest rates unchanged – repo rate at 0%; deposit facility rate at -0.4%; marginal lending facility rate at 0.25% – at its December 13 Governing Council meeting, it also confirmed that its €2.6 trillion asset purchase programme (APP) will be no more by the end of December this year.

At the same time, “…the Governing Council intends to continue reinvesting, in full, the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP for an extended period of time past the date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates, and in any case for as long as necessary to maintain favourable liquidity conditions and an ample degree of monetary accommodation.”

Flashback – that “date when it starts raising the key ECB interest rates” is speculated to be sometime during the late summer of 2019 or “before the last leaf of autumn touched the ground, touched the ground.” (The Cascades).

To be sure, the ECB has boxed itself into a corner. Reneging on its forward guidance to end APP would only confirm financial markets’ concern over the increasing momentum of the slowdown in the region’s economy.

Although the ECB is aware that “uncertainties related to geopolitical factors, the threat of protectionism, vulnerabilities in emerging markets and financial market volatility remain prominent,” it’s optimistic that “the underlying strength of domestic demand continues to underpin the euro area expansion and gradually rising inflation pressures.”

Certainly, optimism is a given for any central banker. Has anyone ever heard a central banker declare, “the sky is falling” or utter Glum’s (of Gulliver’s Travels fame) “we’re doomed, we’ll never make it”? Even ex-Fed chief Ben Bernanke was oozing optimism months (or was it weeks?) before the global financial crisis hit.

I apologise, I may have gone overboard with that simile but the ECB staff’s downward revision to its macroeconomic projections raised a question mark.

The ECB staff lowered its GDP growth forecasts to 1.9% (from 2.0% predicted in September) this year and 1.7% this year and in 2020 (from 1.8% and 1.7%, respectively).

That’s still cool. But if the slowdown in the region’s three biggest economies persists – Germany and Italy are just a quarter away from a technical recession and France’s year-on-year GDP growth have trended lower from 2.8% in the December 2017 quarter to 1.4% in the September 2018 quarter – the risk to growth is on the downside.

Not only this, the ECB staff also revised lower their inflation forecasts for the coming year – HICP inflation at 1.6% in 2019; ex- energy at 1.5%; ex- energy and food at 1.4%; ex- energy, food and changes in indirect taxes at 1.4%. Not only that, all these measures of inflation aren’t expected to reach the ECB’s 2.0% target three years from now – all are forecast to reach 1.8% by 2021.

Still, 2020 or 2021 is still a long way away. Even next year could bring upside or downside surprises – just as the sharp slowdown in euro area GDP growth from a peak of 2.8% in the year to the September 2017 quarter to just 1.6% a year after surprised most.

Global bond yields could see upward pressure if net capital outflows from the eurozone start to subside when the ECB ends its quantitative easing (QE) in December 2018, according to Fitch Ratings.

The latest chart of the month from Fitch’s economics team shows net outflows of capital from the eurozone in the form of long-term portfolio debt instruments. This is calculated as purchases of foreign bonds by eurozone residents minus foreigners’ purchases of eurozone bonds. Net portfolio debt outflows rose sharply after the ECB commenced government bond purchases in early 2015. ECB purchases were substantially greater than the net issuance of new debt to fund eurozone government deficits, implying reduced exposures by existing holders of eurozone government debt. In an environment of increasing scarcity, existing bondholders moved capital to other geographies.

This large net capital outflow has likely helped cap benchmark long-term bond yields in the US (and elsewhere) and a reversal of these flows could drive yields upwards. Since the start of the ECB’s sovereign QE programme, it has bought over EUR2 trillion of bonds while net bond outflows from the eurozone have amounted to EUR1.5 trillion. Eurozone investors now own as many US bonds as Japan and China combined. However, with net QE purchases set to end this year net outflows have already recently started to lose some momentum with foreign selling of eurozone bonds moderating since the start of this year. The risk is that eurozone net bond outflows could drop away sharply when the ECB QE ends in December 2018, reducing demand for US Treasuries and pushing up US (and global) yields.

One factor that could temper such a shock is the ongoing yield advantage of owning US bonds. This is likely to remain a strong pull factor for eurozone investors, as the chart shows. The spread between two-year US Treasuries and German Bunds is at the widest in three decades. The large stock of ECB QE holdings is expected to continue to contain Bund yields, which will remain further anchored by ECB’s negative deposit rate. We believe the ECB deposit rate will be on hold until late next year while the central bank awaits confirmation of firmer underlying inflation trends. Meanwhile the Fed will continue to raise rates.

While the ECB’s dampening influence on global bond yields is likely to weaken significantly from next year, it is unlikely to go away completely.

The European Central Bank said it plans to remove accommodative policy but the euro zone monetary authority had yet to discuss when interest rates would be raised.

The ECB decided to cut its monthly asset purchase program in half to €15 billion at the beginning of October and noted that it was expected to end in December – although reinvestment of proceeds will be maintained. They indicated that interest rates were likely to be on hold for an extended period of time.

The ECB decided to cut its monthly asset purchase program in half to €15 billion at the beginning of October and noted that it was expected to end in December – although reinvestment of proceeds will be maintained. They indicated that interest rates were likely to be on hold for an extended period of time.

“The Governing Council expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at their present levels at least through the summer of 2019 and in any case for as long as necessary to ensure that the evolution of inflation remains aligned with the current expectations of a sustained adjustment path,” the ECB said in its policy decision.

Reiterating that point in the press conference’s question and answer period, president Mario Draghi stressed the “at least through the summer of 2019” and added that “we did not discuss if and when to raise rates.”

The euro, which turned negative against the dollar when the decision was published, extended losses after those remarks.

The euro, which turned negative against the dollar when the decision was published, extended losses after those remarks.

Weaker short-term growth, stronger inflation

The ECB also updated its economic projections and predicted weaker growth along with stronger inflation for this year.

“June 2018 Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area foresee annual real GDP increasing by 2.1% in 2018, 1.9% in 2019 and 1.7% in 2020,” Draghi announced. The 2018 growth forecast was cut from the 2.4% expansion predicted in March.

“The latest economic indicators and survey results are weaker,” Draghi explained, “but remain consistent with ongoing solid and broad-based economic growth.”

Overall, Draghi stated that the risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook remain broadly balanced.

However, he admitted that “uncertainties related to global factors, including the threat of increased protectionism, have become more prominent (and) the risk of persistent heightened financial market volatility warrants monitoring.”

With regard to price stability, the ECB now forecasts annual inflation of 1.7% through 2020, compared to the March projections of 1.4% for this year and next. The estimate for 2020 remained unchanged.

Draghi explained that the changes were made because the ECB felt that progress towards a sustained adjustment in inflation “has been substantial so far”.

“With longer-term inflation expectations well anchored, the underlying strength of the euro area economy and the continuing ample degree of monetary accommodation provide grounds to be confident that the sustained convergence of inflation towards our aim will continue in the period ahead, and will be maintained even after a gradual winding-down of our net asset purchases,” he added.

The European Central Bank (ECB) review of internal models TRIM, is a project to assess whether the internal models currently used by banks comply with regulatory requirements, and whether they are reliable and comparable. Banks sometimes use internal models to determine their Pillar 1 own funds requirements, i.e. the minimum amount of capital they must hold by law. TRIM was launched in late 2015 and is expected to be finalised in 2019. This underscores the ECB’s desire to safeguard internal model use for retail and SME portfolios from the potential imposition of a capital floor.

ECB Banking Supervision is making a large investment in TRIM in terms of its own staff as well as the cost of external resources. With regards to staff, close to 100 ECB and national supervisors will be involved.

The targeted review of internal models, or TRIM, is a project to assess whether the internal models currently used by banks comply with regulatory requirements, and whether they are reliable and comparable. Banks sometimes use internal models to determine their Pillar 1 own funds requirements, i.e. the minimum amount of capital they must hold by law.

One major objective of TRIM is to reduce inconsistencies and unwarranted variability when banks use internal models to calculate their risk-weighted assets (RWAs). This may occur because the current regulatory framework gives banks a certain freedom when modelling their risks.

TRIM also seeks to harmonise practices in relation to specific topics. As a result, the review should help to ensure that internal models are being used appropriately.

Thus, the objectives for TRIM coincide with two major goals of ECB Banking Supervision: to foster a sound and resilient banking system through proactive and tough supervision and to create a level playing field by harmonising supervisory practices across the euro area.

This signals the EU’s determination to restore market confidence in banks’ use of internal models to calculate capital requirements, Fitch Ratings says. It may indicate a desire by the ECB to safeguard internal model use for retail and SME portfolios from the potential imposition of a capital floor.

For the eurozone, whose lawmakers and regulators mostly support the use of internal models and the risk-weighting framework for banks, TRIM is important to their argument that internal models make sense for certain portfolios. The ECB hopes to iron out unwarranted variability between models and restore credibility to the use of internal models, at least for “high-default” portfolios where there is sufficient default data for good-quality modelling.

The ECB’s large investment in TRIM suggests that internal models will continue to play an important role in how eurozone banks compute their regulatory capital requirements. TRIM’s focus on retail and SME credit risk may reveal where the ECB’s focus is for discussions on international bank regulation. The EU may be prepared to lose the use of internal models for “low-default” portfolios, such as financial institutions and large corporates, where it is more of a challenge to model statistically robust estimates for unexpected losses.

TRIM seeks to reduce inconsistencies and unwarranted variability when banks use internal models to calculate their risk-weighted assets (RWAs), by harmonising bank and national supervisory practices relating to models. The ECB has issued a 150-page guide allowing banks to assess themselves against common standards and prepare for the scrutiny to come. TRIM is the biggest single investment made by the ECB in supervision since it started in November 2014. The ECB will lead more than 100 reviews in 2017, involving more than 600 people, at 68 eurozone banks, covering approved internal models for credit, market and counterparty credit risks.

TRIM will take place in 2017 and 2018 with a possible extension into the following year. The ECB will ask banks to put right any shortcomings based on the final version of the guide. We expect the ECB to take a harsher stance with tighter timelines for shortcomings due to the banks’ own practices, while allowing more time to adjust for changes from national standards applied by supervisors in the past. Banks are likely to start work this year on aligning their models with the ECB’s standards. This may lead to movements in RWAs from model changes in 2017-2018, before TRIM is completed in 2019.

Disclosure of RWA movements due to model changes would provide helpful insight to analysts, creditors and investors. These market participants will need to be convinced of the TRIM process if the ECB is to remove their scepticism of RWA calculations based on internal models, in our view.

The current environment of low growth and the resulting low interest rates are already having significant economic, legal and social repercussions.

We are in a phase of weak growth and low interest rates – not only in Europe but in many mature economies. Without there being a final consensus, experts are providing a colourful bunch of possible explanations for the decline in growth potential over the past few years. Regardless of whether the causes are on the demand or supply side, there is broad agreement that the strong relative surplus of savings – some call it a savings glut – has resulted in a worldwide fall in long-term interest rates.

In a speech by Mr Yves Mersch, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, at the University of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Hachenburg, 27 October 2016, he looks at the economic, legal and social implications.

In a speech by Mr Yves Mersch, Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, at the University of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Hachenburg, 27 October 2016, he looks at the economic, legal and social implications.

Impact of low interest rates on the economy

The low interest rate environment is having an impact on our lives in many different ways. Let us start with what you as central bankers of the future will certainly be most interested in: the economic challenges for the European Central Bank (ECB).

Low investment and an increased tendency to save have resulted in a fall in the equilibrium interest rate – the price at which savings and investment are in equilibrium. This is important because this interest rate plays an important role in the orientation of our monetary policy. But more about that later.

Perhaps the greatest risk in such an environment is that individual developments can reinforce one other: the expectation of lower growth in the future can lead to lower investment and excessive saving today.

As I have said before, it is important to avoid a Ricardian angst effect, meaning that persistently low interest rates result in savers developing a higher tendency to save in order to accumulate the same wealth as they would have at higher interest rates.

The fact that the gross savings ratio has been rising again recently in many euro are countries – standing currently at 17.5% in Germany, 14.4% in France – demands our attention.

The International Monetary Fund has put forward similar arguments, warning recently of a “low growth trap“.

Such a development would lead to even lower interest rates, as ever more savings would compete for ever fewer investment opportunities. Greater risks of deflation could ensue.

A central bank cannot disregard such risks. Our mandate is based on maintaining price stability, which is defined as an inflation rate of below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. If we see this objective at risk, we must act.

Let us remind ourselves how monetary policy traditionally works.

In his main work “Geldzins und Güterpreise” (1898), Knut Wicksell investigated the influence of monetary policy on investment and savings behaviour, as well as on the economy. He stated that if the key interest rate is reduced to below the natural interest rate, savings are lower and consumption is higher. The natural rate is “the loan interest rate at which this reacts in an entirely neutral way to goods prices.”

As a result, aggregate demand increases. This will raise the incentives for businesses to invest and they will demand more loans. If the demand for loans is so large that it is not met by the existing savings, the gap will be filled by newly created money.

Interest rate cuts thus lead to loan creation, investment and greater consumption. Investment will lead to higher salaries. As a result, the prices of goods will rise more rapidly. Conversely, higher interest rates dampen demand and price increases.

In short: if the market rate is lower than the natural rate, inflation will tend to occur, and when the opposite is true, then disinflation or even deflation are likely to result.

The problem of a lower equilibrium rate is that it limits a central bank’s leeway for supporting measures. If then in such an environment further economic shocks occur on the demand side, the central bank has to resort rather to unconventional measures, as it can only lower the policy rate to a limited extent.

The package of measures taken by the ECB reflects this situation. It consists of a mixture of conventional and unconventional measures: first of all, we have reduced the key rate to zero, and the rate on the deposit facility is even at -0.4%. In addition, we have launched an asset purchase programme and offered long-term loans to banks at favourable conditions which reward additional loan provision. The aim of all our measures is to keep market rates below their long-term level and thus create an incentive for investment and consumption.

Finally, we want to ensure that the inflation rate over the medium term returns to close to the 2% level. But as long-term interest rates are already at a very low level, market interest rates also have to be low and even negative in order to achieve an appropriate level of support.

In order to assess the effectiveness of our actions, it is important to observe our monetary policy measures not in isolation but as a whole: demand for loans is increasing and our staff estimate that inflation in the euro area will rise to 1.6% in 2018. In 2019 we should largely achieve our aim of below, but close to, 2%. In other words, our monetary policy is working.

However, we are also aware that our measures are having side effects and are keeping this in mind. In particular, we are aware of the fact that these side effects are heightened the longer we maintain our measures. We are therefore keeping a very close eye on the effects that the low or negative interest rate environment has on banks, insurers and savers.

Indeed, banks are complaining that the profitability of their sector is being affected by the low interest rate environment. This is particularly the case for banks whose business model depends heavily on net interest income. First of all, the margins derived from maturity transformation are declining because of the very flat yield curve. And secondly, deposit-based refinancing becomes less profitable, mainly because it is difficult to pass on negative interest rates to private customers.

Some banks have started to charge for deposits over €100,000. Ultimately, however, it will mean that some banks will have to adapt their business models to operate profitably in the long term.

Particularly in Germany there is a need for action. And this is not primarily due to the low interest rate environment. The German banking sector is one of the largest in the euro area, but at the same time the most inefficient. The cost-income ratio of German banks stands at 73%, significantly higher than the rest of the euro area.

And while other countries reduced the number of their banks by almost a quarter following the financial and economic crisis to reduce overcapacity, in Germany it was only 10%. Life insurance companies and pension funds which have promised their customers a nominal rate of return are also coming under pressure: they are finding it difficult to generate these returns in the current market environment. However, we are already seeing that the industry is adapting and focusing somewhat more on unit-linked products, and thus on the more dynamic capital market. However, it is not just banks, insurance companies and pension funds that are suffering from the low interest rates – savers in general are also affected. Private savers are asking whether, in the current environment, it is still worthwhile saving at all. In most cases they take the nominal interest rate of their deposits as a benchmark. In so doing, what they don’t take account of is the real purchasing power of their savings, namely what is left over after deducting the inflation rate. If we consider for instance the real rate of return on bank deposits of private households in Germany since 1991, these generally remained at less than 1%, and sometimes they were even negative. The real overall portfolio return shows large fluctuations over the same period as a result of different factors, and stood just above 1.5% on average between 2008 and early 2015.

In recent years, higher valuation gains above all have supported the overall rate of return, to which our asset purchase programme has also contributed. Because the scope for further valuation gains in the future is estimated to be fairly limited, analysts in Germany are assuming that overall returns in the coming year could decline or even be negative, also because of higher inflation.

These developments suggest that the low-interest phase may lead to a structural change in the financial system, which in turn could give rise to new risks.

Especially in the euro area countries which have been greatly affected by the financial and economic crisis, lending by some banks is still severely constrained by legacy assets resulting from crisis times. On the search for yield and reinforced by technological progress new participants are coming to the fore in these fields. In particular, non-banks, which also go by the unfortunate name of shadow banks, are increasingly active in the traditional banking business. At the same time, sound and liquid companies from the real economy are entering the intermediation market and providing their customers with services that used to be the preserve of banks.

While developments of this kind need not be a bad thing in principle, we should be vigilant and closely monitor the resulting risks. For example, lower lending standards or higher debt levels could result. We also have to bear in mind the liquidity risks and interconnectedness of the various sectors.

Despite all these side effects, I would like to emphasise that the benefits of our monetary policy so far are prevailing. But this situation could change the longer these special circumstances continue. Above all, we need to remember that reactions to interest rate cuts into negative territory do not necessarily follow a linear path.

Moreover, the longer the measures are in place, the less effective they may become. The fact that additional lending in the euro area is losing momentum and that German banks are saying that the negative deposit facility rate is constraining lending volumes warrants attention.

We must be vigilant that this development does not spread to other euro area countries.

So when it comes to deciding what our future monetary policy stance should be, we have to take this into account in our cost/benefit analysis. This applies to instruments, volumes and horizons.

Legal implications

Let me now turn to the legal dimension. I will make a distinction here between private law challenges and the legal framework to which the ECB is subject.

In the financial sector, there are many products whose remuneration is based on a variable interest agreement. This means that the interest rates are regularly adapted to the prevailing market interest rates. The legal position here is very unclear, since in Europe such agreements are subject not only to private law but also to regulatory requirements, based on the implicit assumption that interest rates are always positive in a market economy

This new phenomenon of negative interest rates creates uncertainty and leaves much room for interpretation. This could lead to high legal costs if the need for clarification becomes a matter for the courts.

The legal limits to our monetary policy are, on the other hand, very clearly regulated. The EU Treaties define the objective of our monetary policy measures: maintaining price stability. The ECB has a large measure of freedom in its choice of instruments to achieve this objective. However, it must ensure that the instruments chosen are necessary, appropriate and proportionate. In addition, it must be ensured that the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) “[acts] in accordance with the principle of an open market economy with free competition, favouring an efficient allocation of resources”.

And finally, we are prohibited from conducting monetary financing. This prohibition protects monetary policy against becoming a plaything of fiscal policy. So what may at first sight seem to be a restriction is, in reality, a strengthening of our mandate and our credibility.

All the measures that we have taken over the past few years fall within this legal framework. The European Court of Justice and the German Constitutional Court have confirmed that this is the case, provided that the self-imposed boundaries are observed. We would do well not to shift these boundaries at whim, as this would call the current legal certainty into question.

In the current environment, this means that we are doing and will continue to do everything within our mandate to ensure price stability in the euro area. But it also means that others have to play their part in putting the euro area back on a sustainable growth path over the long term. And I address these remarks principally to the governments of the Member States which need to make progress on the necessary structural reforms in order to make product and labour markets more flexible, to reduce red tape and where possible to invest in education, infrastructure and productivity improvements.

Breeding ground for populist movements

This brings me to my last point: societal change. Like the low interest rate environment in which we as a central bank are operating, the current social dislocation is being caused by, among other things, low growth and the resulting high levels of unemployment in many economic areas. The fact that the recent annual meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank addressed this issue earlier this month shows how important this issue has become.

The solution to these problems does not however lie in the hands of the central banks. As I said, we are only responsible for maintaining price stability. Fiscal redistribution, for example, for the purpose of a politically motivated correction of income differences has to be decided and implemented by democratically elected parliaments. The division of tasks is clear.

Nevertheless, the societal changes over recent years have had an impact on us, and we observe these developments with great concern.

The fact is that many people in our society are finding globalisation difficult. They believe that it only benefits large companies, some of which pursue excessive tax optimisation and question protection rights for individuals – protection rights for those who are doing their bit for society. This sentiment, reinforced by the emotional reactions to the refugee crisis, has discredited the notion of open borders.

In addition, growing uncertainty about secure pension provisions, retaining the value of savings and the deteriorating economic outlook are a breeding ground for populist parties and movements. A growing number of people are ready to sacrifice economic and social freedom for what they believe to be greater security.

In such an environment, it will be more difficult for us, as a central bank, to explain our monetary policy decisions, particularly if some groups feel discriminated against by our decisions, such as savers in Germany. We must take these feelings seriously, although the interest rate on savings reflects the state of the economy and is not primarily the result of monetary policy measures

Our monetary policy measures have prevented the euro area from sliding into a new recession. In the long term our decisions help to stabilise the value of the currency and thus ensure more fairness in society. A Bundesbank study, for example, which considers whether and in what way monetary policy influences the distribution of income and wealth, concludes that it is highly questionable that the expansionary monetary policy measures taken in recent years have increased inequality overall.

Negative interest rates become a worry for banks’ business models if they persist for two or three years, the European Central Bank’s chief economist said on Thursday.

The ECB has charged banks for parking money overnight since June 2014, leading to complaints from lenders that their margins are being squeezed because they cannot pass on the charge to their depositors.

In his clearest acknowledgment to date of banks’ concerns, Peter Praet said: “The persistence of negative rates over time — two, three years — is something that becomes quite worrisome if you think about the implications for business models.”

In addition, Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, in his speech, indicated that measures taken by the ECB, including negative interest rate policy is sizeable (again excluding the March 2016 decisions). According to their staff assessment, the policy is contributing to raise euro area GDP by around 1.5% in the period 2015-18.