During the 2007-2009 global financial crisis, many central banks in the world, including the Federal Reserve, cut interest rates and resorted to various unconventional policies in order to fight financial market disruption, high unemployment, and low or negative economic growth. Now, in 2016, these central banks are typically experiencing inflation below their targets, and they seem powerless to correct the problem. Further unconventional monetary policy actions do not seem to help.

Neo-Fisherites argue that the solution to too-low inflation is obvious, and it may have been just as obvious to Irving Fisher, the early 20th century American economist and original Fisherite. The key Neo-Fisherian principle is that central banks can increase inflation by increasing their nominal interest rate targets—an idea that may seem radical at first blush, as central bankers typically believe that cutting interest rates increases inflation.

To see where Neo-Fisherian ideas come from, it helps to understand the roots of the science of modern central banking. Two key developments in central banking since the 1960s were the recognition that: (1) the responsibility for inflation lies with the central bank; and (2) the main instrument for monetary control for the central bank is a short-term (typically overnight) nominal interest rate. These developments were driven largely by monetarist ideas and by the experience with the implementation of those ideas by central banks in the 1970s and 1980s.

Monetarism is best-represented in the work of the economist Milton Friedman, who argued that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” and that inflation can and should be managed through central bank control of the stock of money in circulation. Friedman reasoned that the best approach to inflation control is the adoption by the central bank of a constant money growth rule: He thought the central bank should choose some monetary aggregate—a measure of the total quantity of currency, accounts with commercial banks and other retail payments instruments (for example, M1)—and conduct monetary policy in such a way that this monetary aggregate grows at a constant rate forever. The higher the central bank’s desired rate of inflation, the higher should be this constant money growth rate.

During the 1970s and 1980s, many central banks, including the Fed, adopted money growth targets as a means for bringing down the relatively high rates of inflation at that time. Monetarist ideas were a key element of the policies adopted by Paul Volcker, chairman of the Fed’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) from 1979 to 1987. He brought the inflation rate down from about 10 percent at the beginning of his term to 3.5 percent at the end through a reduction in the rate of growth in the money supply.

Though monetarist ideas were useful in bringing about a large reduction in the inflation rate, Friedman’s constant-money-growth prescription did not work as an approach to managing inflation on an ongoing basis. Beginning about 1980, the relationship between money growth and inflation became much more unstable, due in part to changes in financial regulation, technological changes in the banking industry and perhaps to monetarist monetary policy itself. This meant that using Friedman’s prescriptions to fine-tune policy to target inflation over the long term would not work.

As a result, most central banks, including the Fed, abandoned money-growth targeting in the 1980s. As an alternative, some central banks adopted explicit inflation targets, which have since become common. For example, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of Japan have targets of 2 percent for the inflation rate. The U.S. is somewhat unusual in that Congress has specified a “dual mandate” for the Fed, which, since 2012, the Fed has interpreted as a 2 percent inflation target combined with the pursuit of “maximum employment.”

Conventional Practice

If a central bank is to move inflation toward its inflation target without reference to the growth rate in a measure of money, how is it supposed to proceed? Central banks control inflation indirectly by relying on an intermediate instrument—typically an overnight nominal interest rate. In the U.S., the FOMC sets a target for the overnight federal funds rate (fed funds rate) and sends a directive to the New York Federal Reserve Bank, which has the responsibility of reaching the target through intervention in financial markets.

Conventional central banking practice is to increase the nominal interest rate target when inflation is high relative to the inflation target and to decrease the target when inflation is low. The reasoning behind this practice is that increasing interest rates reduces spending, “cools” the economy and reduces inflation, while reducing interest rates increases spending, “heats up” the economy and increases inflation.

Neo-Fisherism

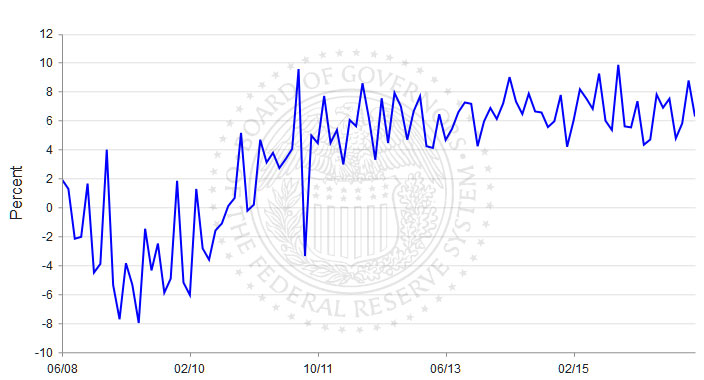

But what if central banks have inflation control wrong? A well-established empirical regularity, and a key component of essentially all mainstream macroeconomic theories, is the Fisher effect—a positive relationship between the nominal interest rate and inflation. The Fisher relationship, named for Irving Fisher, is readily discernible in the data.

This is a scatter plot of the inflation rate (the four-quarter percentage change in the personal consumption deflator—the Fed’s chosen measure of inflation) vs. the fed funds rate for the period 1954-2015. A positively sloped line would be the best fit to the points in the scatter plot, indicating that inflation tends to rise as the fed funds rate rises.

Many macroeconomists have interpreted the Fisher relation observed as involving causation running from inflation to the nominal interest rate (the usual market quote for the interest rate, not adjusted for inflation). Market interest rates are determined by the behavior of borrowers and lenders in credit markets, and these borrowers and lenders care about real rates of interest. For example, if I take out a car loan for one year at an interest rate of 10 percent, and I expect the inflation rate to be 2 percent over the next year, then I expect the real rate of interest that I will face on the car loan will be 10 percent – 2 percent = 8 percent. Since borrowers and lenders care about real rates of interest, we should expect that as inflation rises, nominal interest rates will rise as well. So, for example, if the typical market interest rate on car loans is 10 percent if the inflation rate is expected to be 2 percent, then we might expect that the market interest rate on car loans would be 12 percent if the inflation rate were expected to be 4 percent. If we apply this idea to all market interest rates, we should anticipate that, generally, higher inflation will cause nominal market interest rates to rise.

But, what if we turn this idea on its head, and we think of the causation running from the nominal interest rate targeted by the central bank to inflation? This, basically, is what Neo-Fisherism is all about. Neo-Fisherism says, consistent with what we see in, that if the central bank wants inflation to go up, it should increase its nominal interest rate target, rather than decrease it, as conventional central banking wisdom would dictate. If the central bank wants inflation to go down, then it should decrease the nominal interest rate target.

But how would this work? To simplify, think of a world in which there is perfect certainty and where everyone knows what future inflation will be. Then, the nominal interest rate R can be expressed as

R = r + π,

where r is the real (inflation-adjusted) rate of interest and π is future inflation. Then, suppose that the central bank increases the nominal interest rate R by raising its nominal interest rate target by 1 percent and uses its tools (intervention in financial markets) to sustain this forever. What happens? Typically, we think of central bank policy as affecting real economic activity—employment, unemployment, gross domestic product, for example—through its effects on the real interest rate r. But, as is widely accepted by macroeconomists, these effects dissipate in the long run. So, after a long period of time, the increase in the nominal interest rate will have no effect on r and will be reflected only in a one-for-one increase in the inflation rate, π. In other words, in the long run, the only effect of the nominal interest rate on inflation comes through the Fisher effect; so, if the nominal interest rate went up by 1 percent, so should the inflation rate—in the long run.

But, in the short run, it is widely accepted by macroeconomists (though there is some disagreement about the exact mechanism) that an increase in R will also increase r, which will have a negative effect on aggregate economic activity—unemployment will go up and gross domestic product will go down. This is what macroeconomists call a non-neutrality of money. But note that, if an increase in R results in an increase in r, the short-run response of inflation to the increase in R must be less than one-for-one.

However, if inflation is to go down when R goes up, the real interest rate r must increase more than one-for-one with an increase in R, that is, the non-neutrality of money in the short run must be very large.

To assess these issues thoroughly, we need a well-specified macroeconomic model. But essentially all mainstream macroeconomic models predict a response of the economy to an increase in the nominal interest rate as depicted below.

In this figure, time is on the horizontal axis, and the central bank acts to increase the nominal interest rate permanently, and in an unanticipated fashion, at time T. This results in an increase in the real interest rate r on impact. Inflation π increases gradually over time, and the real interest rate falls, with the inflation rate increasing by the same amount as the increase in R in the long run. This type of response holds even in mainstream New Keynesian models, which, it is widely believed, predict that a central bank wanting to increase inflation should lower its nominal interest rate target. However, as economist John Cochrane shows, the New Keynesian model implies that if the central bank carries out the policy we have described—a permanent increase of 1 percent in the central bank’s nominal interest rate target—then the inflation rate will increase, even in the short run.

The Low-Inflation Policy Trap

What could go wrong if central bankers do not recognize the importance of the Fisher effect and instead conform to conventional central banking wisdom? Conventional wisdom is embodied in the Taylor rule, first proposed by John Taylor in 1993. Taylor’s idea is that optimal central bank behavior can be written down in the form of a rule that includes a positive response of the central bank’s nominal interest rate target to an increase in inflation.

But the Taylor rule does not seem to make sense in terms of what we see. Taylor appears to have thought, in line with conventional central banking wisdom, that increasing the nominal interest rate will make the inflation rate go down, not up. Further, Taylor advocated a specific aggressive response of the nominal interest rate target to the inflation rate, sometimes called the Taylor principle. This principle is that the nominal interest rate should increase more than one-for-one with an increase in the inflation rate.

So, what happens in a world that is Neo-Fisherian (the inflationary process works as above, but central bankers behave as if they live in Taylor’s world? Macroeconomic theory predicts that a Taylor-principle central banker will almost inevitably arrive at the “zero lower bound.” What does that mean?

Until recently, macroeconomists argued that short-term nominal interest rates could not go below zero because, if interest rates were negative, people would prefer to hold cash, which has a nominal interest rate equal to zero. According to this logic, the lower bound on the nominal interest rate is zero. It turns out that, if the central bank follows the Taylor principle, then this implies that the central bank will see inflation falling and will respond to this by reducing the nominal interest rate. Then, because of the Fisher effect, this actually leads to lower inflation, causing further reductions in the nominal interest rate by the central bank and further decreases in inflation, etc. Ultimately, the central bank sets a nominal interest rate of zero, and there are no forces that will increase inflation. Effectively, the central bank becomes stuck in a low-inflation policy trap and cannot get out—unless it becomes Neo-Fisherian.

But maybe this is only theory. Surely, central banks would not get stuck in this fashion in reality, misunderstanding what is going on, right? Unfortunately, not. The primary example is the Bank of Japan. Since 1995, this central bank has seen an average inflation rate of about zero, having kept its nominal interest rate target at levels close to zero over those 21 years. The Bank of Japan has an inflation target of 2 percent and wants inflation to be higher, but seems unable to achieve what it wants.

Over the past several years, membership in the low-inflation-policy-trap club of central banks has been increasing. This club includes the European Central Bank, whose key nominal interest rate is –0.34 percent and inflation rate is –0.22 percent; the Swedish Riksbank, with key nominal interest rate of –0.50 percent and inflation rate of 0.79 percent; the Danish central bank, with key nominal interest rate of –0.23 percent and inflation rate of 0 percent; the Swiss National Bank, with key nominal interest rate of –0.73 percent and inflation rate of –0.35 percent; and the Bank of England, with key nominal interest rate of 0.47 percent and inflation rate of 0.30 percent. Each of these central banks has been missing its inflation target on the low side, in some cases for a considerable period of time. The Fed could be included in this group, too, as the fed funds rate was targeted at 0-0.25 percent for about seven years, until Dec. 16, 2015, when the target range was increased to 0.25-0.50 percent. The Fed has missed its 2 percent inflation target on the low side for about four years now.

How a Trapped Central Bank Behaves

Abandoning the Taylor principle and embracing Neo-Fisherism seems a difficult step for central banks. What they typically do on encountering low inflation and low nominal interest rates is engage in unconventional monetary policy. Indeed, unconventional policy has become commonplace enough to become respectably conventional.

Unconventional monetary policy takes three forms in practice. First, central banks can push market nominal interest rates below zero (relaxing the zero lower bound) by paying negative interest on reserves at the central bank—charging a fee on such accounts, as has been done by the Bank of Japan, the Swiss National Bank, the Danish central bank and the Swedish Riksbank. Second, there can be so-called quantitative easing, or QE—the large-scale purchase of long-maturity assets (government debt and private assets, such as mortgage-backed securities) by a central bank. Such programs have been an important element of monetary policy in the U.S., Switzerland and Japan, for example, in the years after the financial crisis (2007-2009). Third, central banks can engage in forward guidance—promises concerning what they will do in the future. Typically, these are promises that interest rates will stay low in the future, in the hope that this will increase inflation. But will any of these unconventional policies actually work to increase the inflation rate? Neo-Fisherism suggests not.

First, given the Fisher effect, a negative nominal interest rate will only make the inflation rate lower, as has happened in Switzerland, where nominal interest rates have been negative for some time and there is deflation—negative inflation. Second, some theory indicates that QE either does not work at all or acts to make inflation lower. This is consistent with what we have seen in Japan, where an extensive QE program in place for two years has not yielded higher inflation. Third, forward guidance, which promises more of the same unconventional policies and continued low interest rates if the low-inflation problem persists, will only prolong the problem.

Conclusion

Among the major central banks in the world, the Fed stands out as the only one that is pursuing a policy of increases in its nominal interest rate target. This policy, referred to as “normalization,” was initiated in December 2015. Normalization, however, is projected to take place slowly and is not motivated explicitly by Neo-Fisherian ideas, though James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, has shown interest.

What is the risk associated with Neo-Fisherian denial—a failure to take account of the Fisher relation in formulating monetary policy? Neo-Fisherian denial will tend to produce inflation lower than central banks’ inflation targets and nominal interest rates that are at central banks’ effective lower bounds—the low-inflation policy trap. But what of it? There are no good reasons to think that, for example, 0 percent inflation is worse than 2 percent inflation, as long as inflation remains predictable. But “permazero” damages the hard-won credibility of central banks if they claim to be able to produce 2 percent inflation consistently, yet fail to do so. As well, a central bank stuck in a low-inflation policy trap with a zero nominal interest rate has no tools to use, other than unconventional ones, if a recession unfolds. In such circumstances, a central bank that is concerned with stabilization—in the case of the Fed, concerned with fulfilling its “maximum employment” mandate—cannot cut interest rates. And we know that a central bank stuck in a low-inflation trap and wedded to conventional wisdom resorts to unconventional monetary policies, which are potentially ineffective and still poorly understood.