REIA president Malcolm Gunning said first-home buyers now make up 24.5 per cent of the total owner occupied housing market, excluding refinancing.

“This is the highest rate since September 2013,” he said, noting the rate had been dropping steadily for the last five years until this latest rise.

Gunning said the number of first home buyers increased by 22.8 per cent over the quarter and 32.6 per cent over the year.

Darren Kasehagen, Head of Business Development, Adelaide Bank said, “The increase in housing affordability across all states and territories is to be welcomed and is reflected by heightened activity in the number of first home buyers coming back into the market.

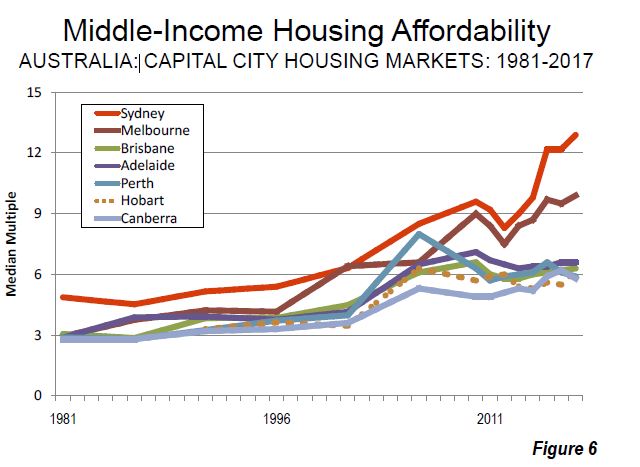

“Housing affordability is still a major issue in Sydney and Melbourne, but there are some bright spots in the latest report from the other capitals that are also worthy of note.

The largest increases in first-home buyers were New South Wales (up 57.7 per cent), Victoria (up 32.2 per cent), the Northern Territory (up 14.3 per cent) and the Australian Capital Territory (up 20.0 per cent).

“Nationally, the average loan size to first home buyers increased to $319,500, or by 0.6 per cent over the September quarter – but decreased by 0.1 per cent over the past twelve months,” said Kasehagen.

For all borrowers, the average loan size decreased to $380,900 with the total number of loans increasing by 4.2 per cent for the quarter or 12.5 per cent year on year.

Rental market affordability

The report shows varied affordability across rental markets.

“Over the quarter, the proportion of median family income required to meet rent payments increased by 0.3 percentage points to 24.6 per cent,” said Gunning.

Rental affordability improved in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, he said, and remained steady in Victoria but declined in New South Wales, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.

Western Australia recorded a “standout” result, said Kasehagen.

Western Australia knocked the ACT from their position of being the state or territory with the lowest proportion of family income devoted to meeting median rents. Western Australians only contribute 17.4 per cent of their family income to rent, according to the report. The figure for Canberra was 18.1 per cent.

“This bides well for future first home buyers in the West seeking to build a deposit and take the step toward eventual home ownership,” said Kasehagen.

In Canberra, 18.5 per cent of family income in Canberra was devoted to meeting average loan repayments – the lowest percentage in the country. The gap between renting and buying in Canberra is now only 0.4 per cent, said Kasehagen.

“An equation that may see more people now renting in the ACT deciding to take the step towards home ownership,” he said.

Adelaide Bank/REIA Housing Affordability Report: State by State

New South Wales

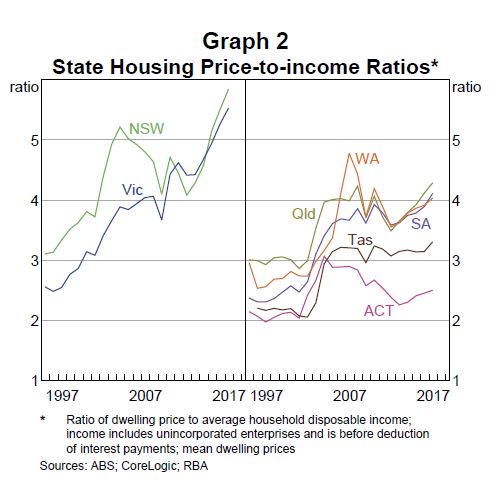

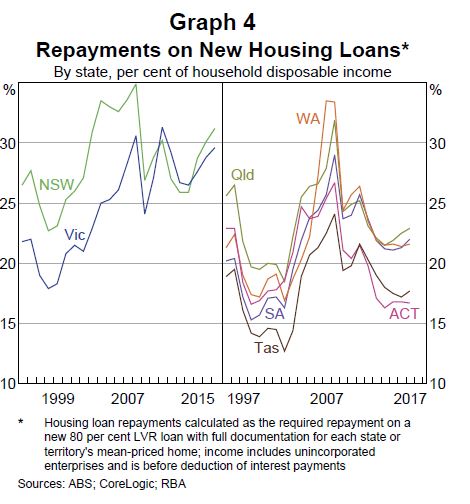

Over the September quarter, housing affordability in New South Wales improved with the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments decreasing to 36.1 per cent, a fall of 1.9 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.0 percentage points compared with the corresponding quarter 2016. With the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments 5.8 percentage points higher than the nation’s average, New South Wales remained the least affordable state or territory in which to buy a home.

In New South Wales, the number of loans to first home buyers increased to 6,775, an increase of 57.7 per cent over the quarter and a rise of 70.9 per cent compared to the September quarter 2016. Of the total number of first home buyers that purchased during the September quarter, 23.4 per cent were from New South Wales while first home buyers make up 19.0 per cent of the State’s owner-occupier market. The average loan to first home buyers decreased to $361,333, a decrease of 1.2 per cent over the quarter and a decrease of 1.0 per cent compared to the same quarter last year.

Rental affordability, declined in New South Wales over the September quarter with the proportion of income required to meet median rent payments increasing to 29.8 per cent, an increase of 1.2 percentage points over the September quarter and an increase of 1.7 percentage points compared to the same quarter last year.

Victoria

Over the September quarter, housing affordability improved in Victoria with the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments decreasing to 32.2 per cent, a decrease of 1.2 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 0.2 percentage points compared to the same quarter of the previous year.

The number of loans to first home buyers in Victoria increased to 8,786, an increase of 32.2 per cent over the quarter and an increase of 33.0 per cent compared to the September quarter 2016. Of the total number of first home buyers that purchased during the September quarter, 30.4 per cent were from Victoria while first home buyers make up 26.2 per cent of the State’s owner-occupier market.

Rental affordability in Victoria has remained steady over the quarter with the proportion of income required to meet median rent remaining at 23.1 per cent. Compared to the September quarter 2016, rental affordability has declined with the proportion of income required to median rent increasing by 0.2 percentage points.

Queensland

Housing affordability in Queensland improved over the September quarter with the proportion of income required to meet home loan repayments decreasing to 26.8 per cent, a decrease of 0.5 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.0 percentage points compared to the same quarter last year.

Over the September quarter, the number of loans to first home buyers in Queensland increased to 6,271, an increase of 4.5 per cent over the quarter and an increase of 18.5 per cent compared to the same quarter of 2016. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 21.7 per cent were from Queensland while the proportion of first home buyers of the State’s owner-occupier market was 26.1 per cent.

Rental affordability in Queensland improved over the quarter with the proportion of the median family income required to meet the median rent decreasing to 22.8 per cent, a decrease of 0.2 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 0.6 percentage points compared to the same quarter 2016.

South Australia

Over the September quarter, housing affordability in South Australia improved with the proportion of income required to meet monthly loan repayments decreasing to 25.3 per cent, a decrease of 1.5 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease 1.1 percentage points compared to the September quarter 2016.

Over the September quarter, the number of loans to first home buyers in South Australia increased to 1,385, an increase of 2.0 per cent over the quarter and an increase of 12.6 per cent compared to the September quarter 2016. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 4.8 per cent were from South Australia while the proportion of first home buyers in the state’s owner-occupier market was 19.2 per cent.

Rental affordability in South Australia also improved over the quarter with the proportion of income required to meet rent payments decreasing to 21.7 per cent, a decrease of 0.2 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 0.7 percentage points compared to the September quarter 2016.

Western Australia

Over the September quarter, housing affordability in Western Australia improved with the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments decreasing to 22.4 per cent, a decrease of 1.2 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.4 percentage points compared to the September quarter 2016.

The number of first home buyers in Western Australia increased to 4,432 in the September quarter, an increase of 7.4 per cent over the quarter and an increase of 17.9 per cent compared to the same time last year. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 15.3 per cent were from Western Australia while the proportion of first home buyers in the state’s owner-occupier market was 36.2 per cent.

Rental affordability in Western Australia also improved during the September quarter with the proportion of family income required to meet the median rent decreasing to 17.4 per cent, a decrease of 0.7 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.8 percentage points compared to the year before.

Tasmania

Housing affordability in Tasmania improved over the September quarter with the proportion of income required to meet home loan repayments decreasing to 23.3 per cent, a decrease of 0.6 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 0.5 percentage points from the September quarter 2016.

The number of first home buyers in Tasmania increased to 386, an increase of 1.6 per cent over the quarter but a decrease of 3.3 per cent compared to the same quarter of the previous year. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 1.3 per cent were from Tasmania while the proportion of first home buyers in the state’s owner-occupier market was 17.5 per cent.

Rental affordability in Tasmania, however, declined over the quarter with the proportion of income required to meet median rents increasing to 26.3 per cent, an increase of 0.5 percentage points over the quarter and an increase of 2.3 percentage from the same quarter 2016.

Northern Territory

Housing affordability in the Northern Territory improved with the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments decreasing to 19.4 per cent in the September quarter, a decrease of 0.9 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.1 percentage points when compared to the September quarter 2016.

The number of loans to first home buyers in the Northern Territory increased to 200, an increase of 14.3 per cent over the September quarter and an increase of 37.9 per cent compared to the September quarter 2016. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 0.7 per cent were from the Northern Territory while the proportion of first home buyers in the Territory’s owner-occupier market was 28.8 per cent.

Rental affordability in the Northern Territory also improved over the quarter with the proportion of income required to meet the median rent decreasing to 22.7 per cent, a decrease of 0.4 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 2.0 percentage points compared to the September quarter 2016.

Australian Capital Territory

Housing affordability in the Australian Capital Territory improved over the September quarter with the proportion of income required to meet home loan repayments decreasing to 18.5 per cent, a decrease of 1.3 percentage points over the quarter and a decrease of 1.5 percentage points compared to the same quarter last year.

The number of loans to first home buyers in the Australian Capital Territory increased to 684, an increase of 20.0 per cent over the quarter and an increase of 64.4 per cent compared to the September quarter 2016. Of all Australian first home buyers over the quarter, 2.4 per cent were from the Australian Capital Territory while the proportion of first home buyers in the Territory’s owner-occupier market was 26.8 per cent.

Rental affordability in the Australian Capital Territory, however, declined over the September quarter with the proportion of income required to meet the median rent increasing to 18.1 per cent, an increase 0.2 percentage points over the quarter and an increase of 0.8 percentage points compared to the September quarter 2016.

The HIA Affordability Index is produced quarterly and measures the mortgage repayment burden as a proportion of typical earnings in each market. A higher index result signifies a more favourable affordability

The HIA Affordability Index is produced quarterly and measures the mortgage repayment burden as a proportion of typical earnings in each market. A higher index result signifies a more favourable affordability