From Investor Daily. An excellent piece by James Mitchell.

The International Monetary Fund has recommended that APRA takes a forensic “deep dive” into the credit risk management frameworks of Australian banks.

The IMF has released its Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) report on Australia. While the comprehensive review was generally positive towards the domestic economy and the role of the prudential regulator, it did warn of key risks to the financial system.

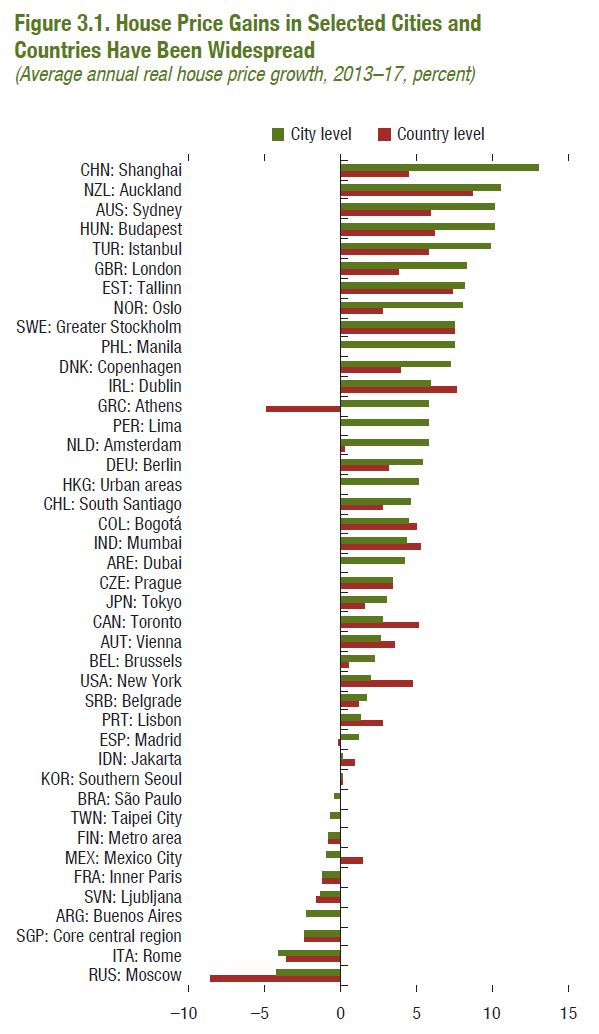

The IMF noted that stretched real estate valuations and high household debt pose macro-prudential risks to Australia.

“House prices, after rising by about 70 per cent over the past decade at the national level, have now started to decline,” the report said.

“The price appreciation following the global financial crisis had been even higher in Sydney and Melbourne, where prices had doubled on average over 10 years, though these two cities have also experienced sharper falls in recent months.

“Commercial real estate prices, particularly for office space, also rose sharply in the major cities over the past decade but have shown few signs of cooling as yet. Housing affordability linking incomes to prices is near all-time lows.”

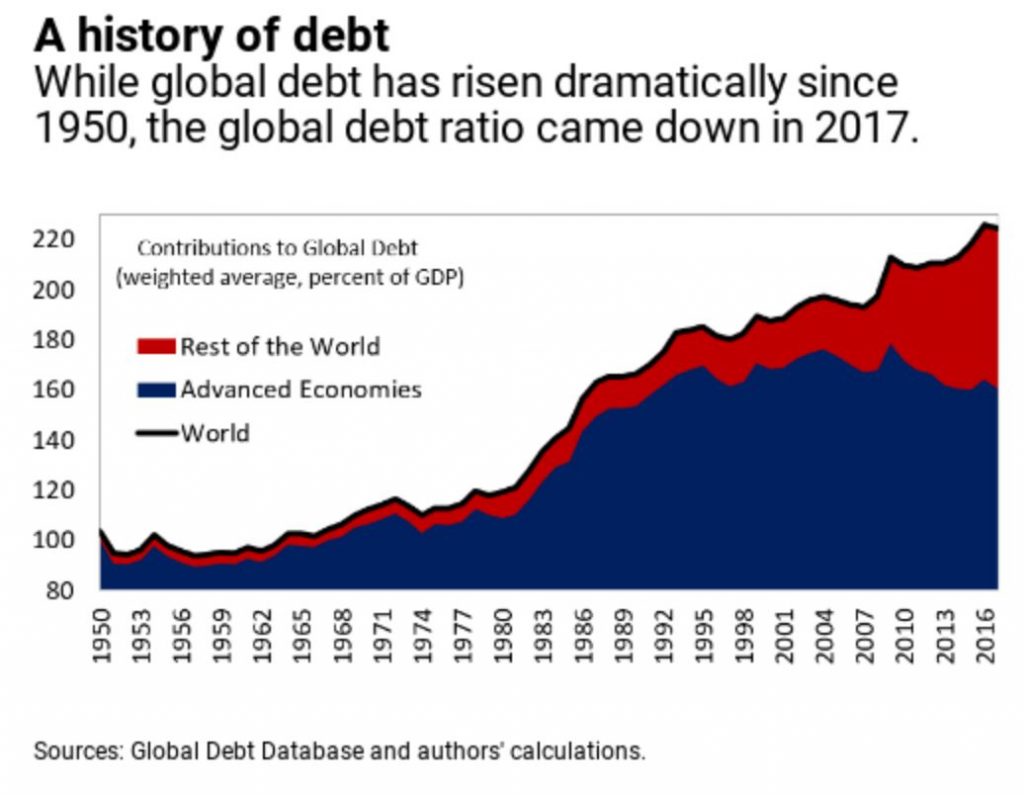

The IMF noted that in recent years, benign credit conditions and the surge in house prices contributed to rapidly rising household leverage. Household debt currently stands at some 190 per cent of disposable income, around 25 basis points higher than in 2012, when the last FSAP report was produced.

The report noted that this is “very high by international standards”. Australian household debt-to-income levels are now almost twice as high as the United States and Japan and exceed the levels in the UK and Canada.

While macro-prudential measures have contributed to the easing of pressures in the housing market, and a soft landing of the housing market is the most likely baseline, the IMF warned that there are risks of a stronger downturn.

“A sharp correction in real estate markets could lead to a vicious feedback loop of falling real estate valuations, higher nonperforming loans, tighter bank credit, falling consumer confidence, and weaker growth, as happened during the global financial crisis (GFC),” the report said.

“The impact on banks would be largely through credit losses as they all carry large exposures to the housing market and to CRE. Additionally, weaker banks could experience an outflow of customer deposits or a significant decline in wholesale funding.”

The IMF has recommended that APRA supervisors should continue scrutinising banks’ underwriting practices, particularly in retail loans (including residential mortgages) and in the commercial real estate lending sector.

Critically, the report recommends that APRA supervisors should consider undertaking periodic deep dives into banks’ credit risk management framework depending on the risks and controls of ADIs.

In addition to house prices and household debt, Australia’s financial system could be significantly impacted by a slowdown in China, the report warned.

Rising global protectionism could provide one catalyst.

“While Australian banks’ direct exposure to China is relatively small (about 4 per cent of overall claims), the economy has much larger exposure via the trade channel,” the report said.

“One-third of Australian goods exports, including 40 per cent of commodities, go to China. Moreover, the growth of services exports to China in recent years has been particularly strong in the areas of tourism and education.

“A sharp slowdown in Chinese growth would lower Australian export revenues markedly. Banks would likely face higher losses on corporate lending, as well as on their broader credit portfolio due to the overall decline in economic activity.”

In its review of the Australian banking sector, the IMF observed that while ADIs are reasonably liquid, profitable and well capitalised, they have oriented their business models towards residential lending in recent years.

While the IMF noted APRA’s efforts to cool residential lending via macro-prudential measures in recent years, the report noted that “significant structural vulnerabilities persist in the financial system”.

“Household indebtedness remains very high, while banks’ portfolios continue to be concentrated and heavily exposed to the residential mortgage sector.

“Banks are exposed to rollover risk on their overseas funding. Wholesale funding dependence has diminished but remains around one-third of total funding, of which nearly two-thirds is from international sources.”

The IMF noted that the Australian tax system provides incentives for leveraged investment by households, including in residential real estate that contributes to the elevated structural vulnerabilities.

“There are also few signs of cooling in the commercial real estate sector where prices have risen sharply in recent years. While bank exposures to the sector are significantly smaller than to households, the sector is highly cyclical and typically experiences high default rates during severe downturns.”