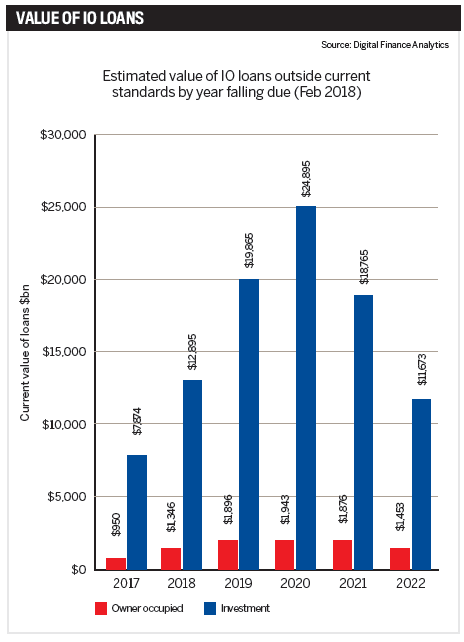

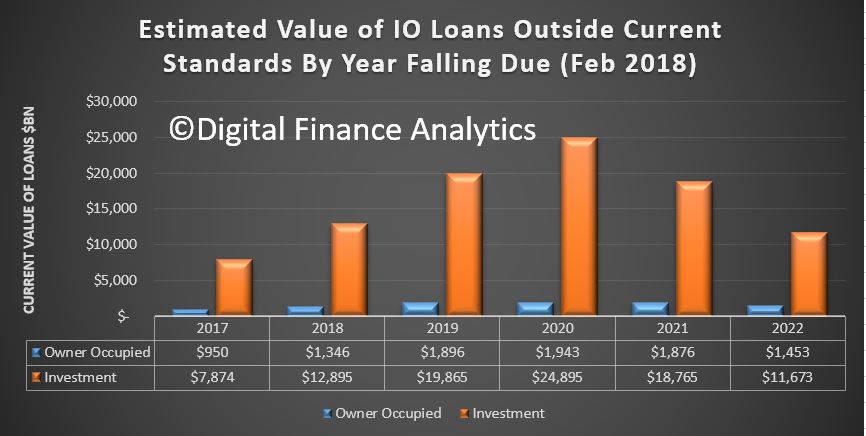

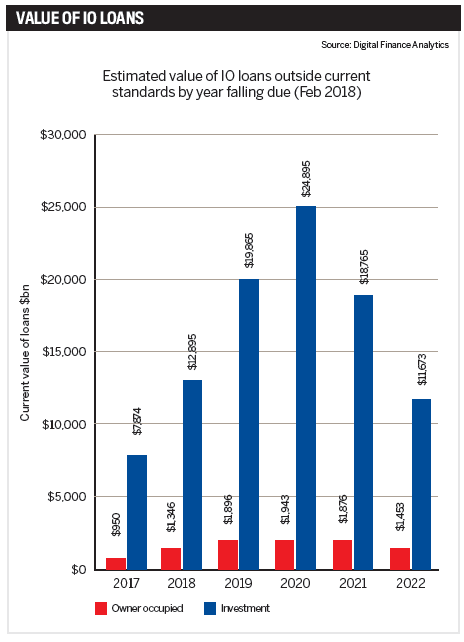

The regulators aren’t the only ones concerned. In February, assistant governor Michele Bullock delivered a speech on mortgage stress in which she highlighted a “large proportion of interest-only loans are due to expire between 2018 and 2022”.

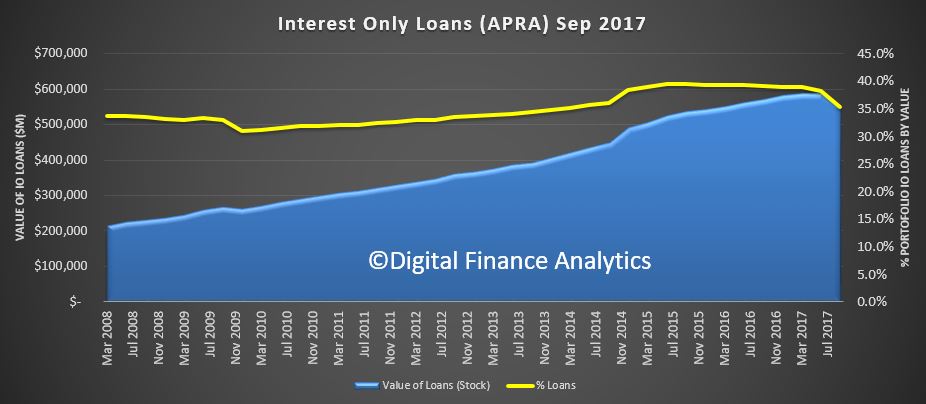

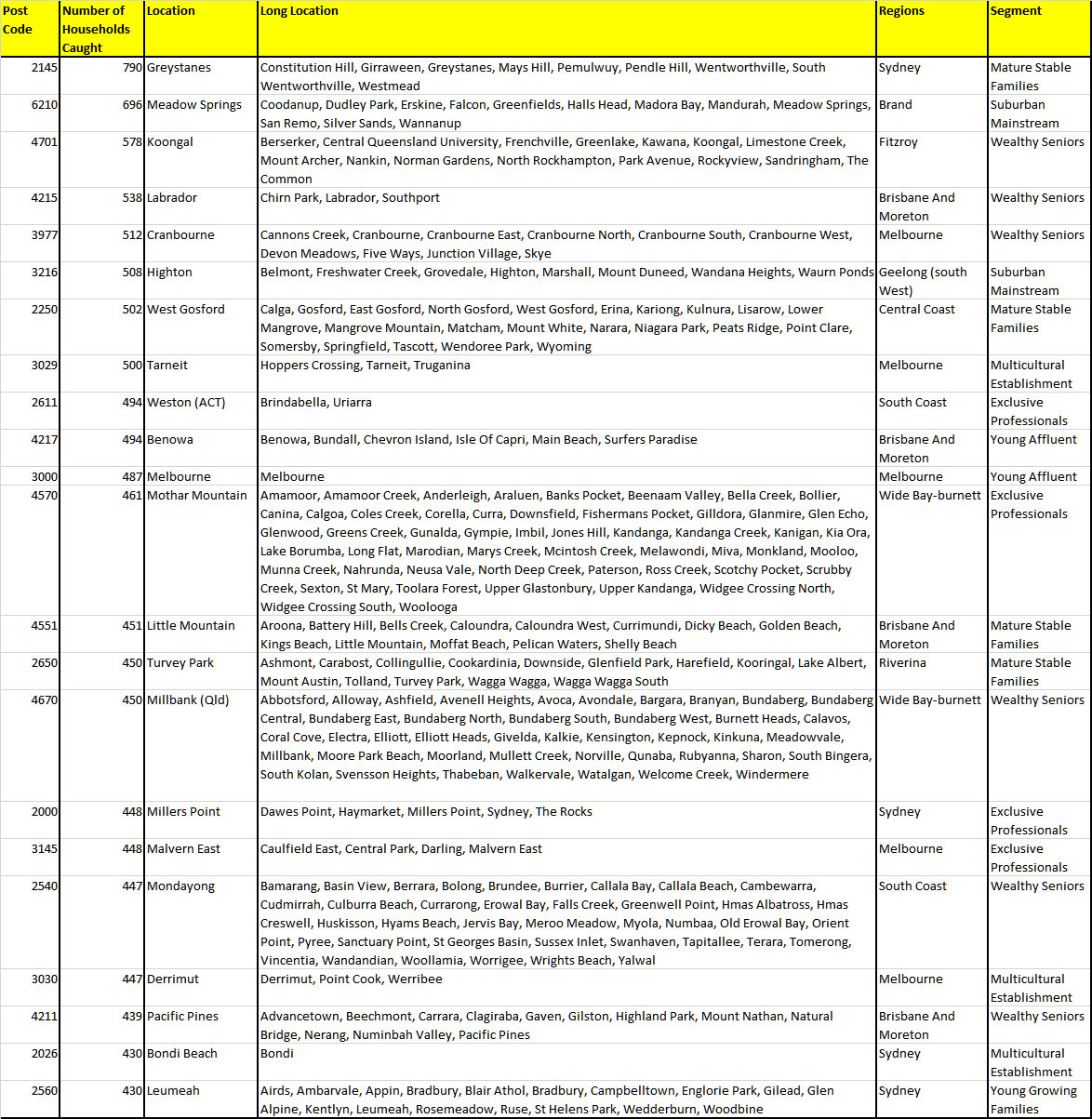

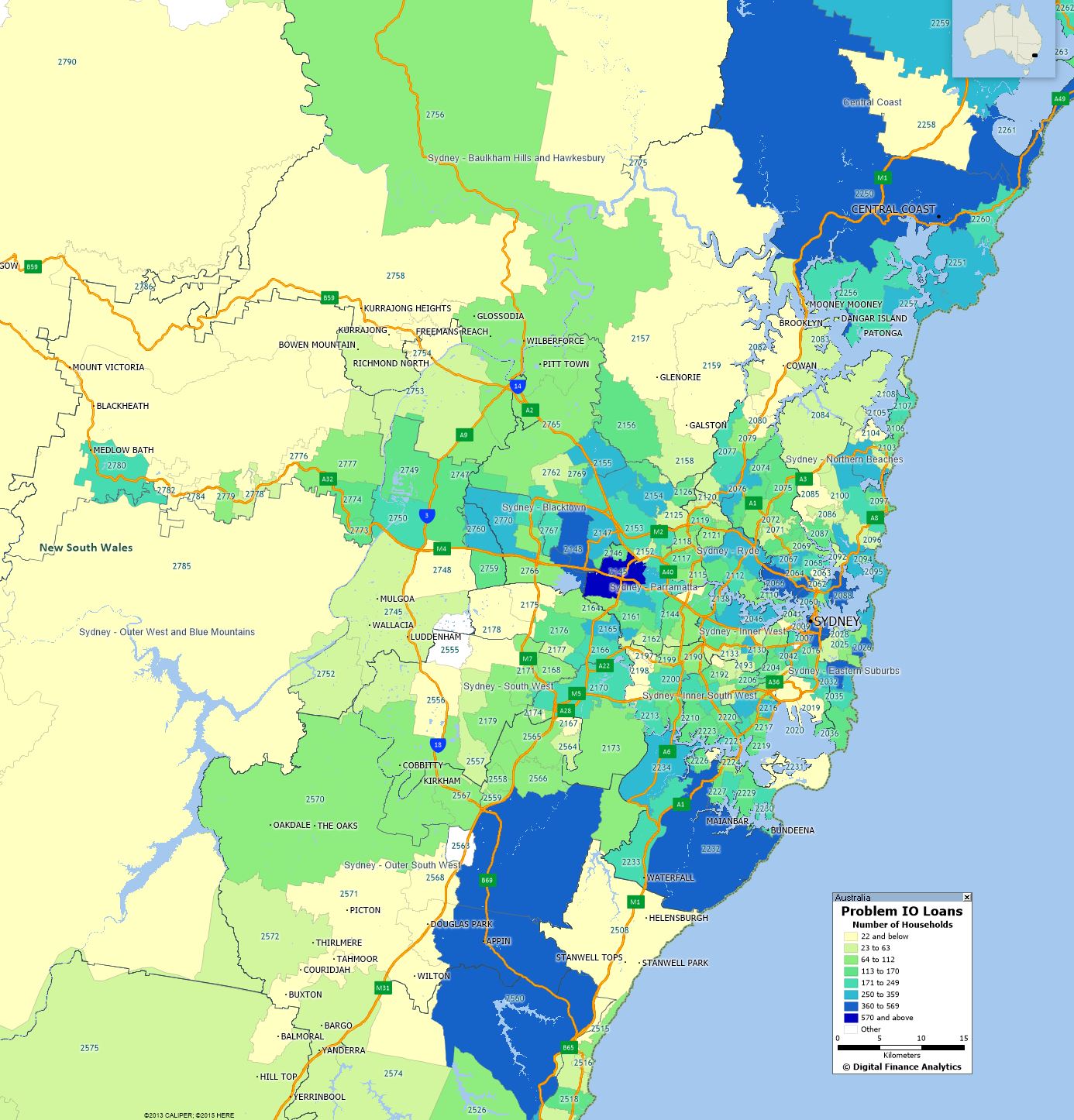

That large proportion is, in fact, almost every IO loan written between 2013 and 2016, and subsequent analysis of IO property fixed-term lending by Digital Finance Analytics has calculated the total number at 220,000, with values upwards of $100bn.

These loans originate from before the reviews of 2015 and 2017, and in the coming year the fixed terms on 14% of them will face a reset outside of current lending criteria. By 2020, the value of loans due for renegotiation is expected to reach $27bn.

While there are many options open to these borrowers, Bullock calls it an “area to watch”, saying many could find themselves in financial stress.

“Some homeowners may not realise they are fast approaching the end of their five-year term and, if they do nothing, their lender will automatically roll them onto a P&I loan that could be challenging for them to support,” says Zippy Loans’ principal broker Louisa Sanghera.

“Combine this scenario with a slowing of the property market and clients may not have the buffer of equity to soften the blow.”

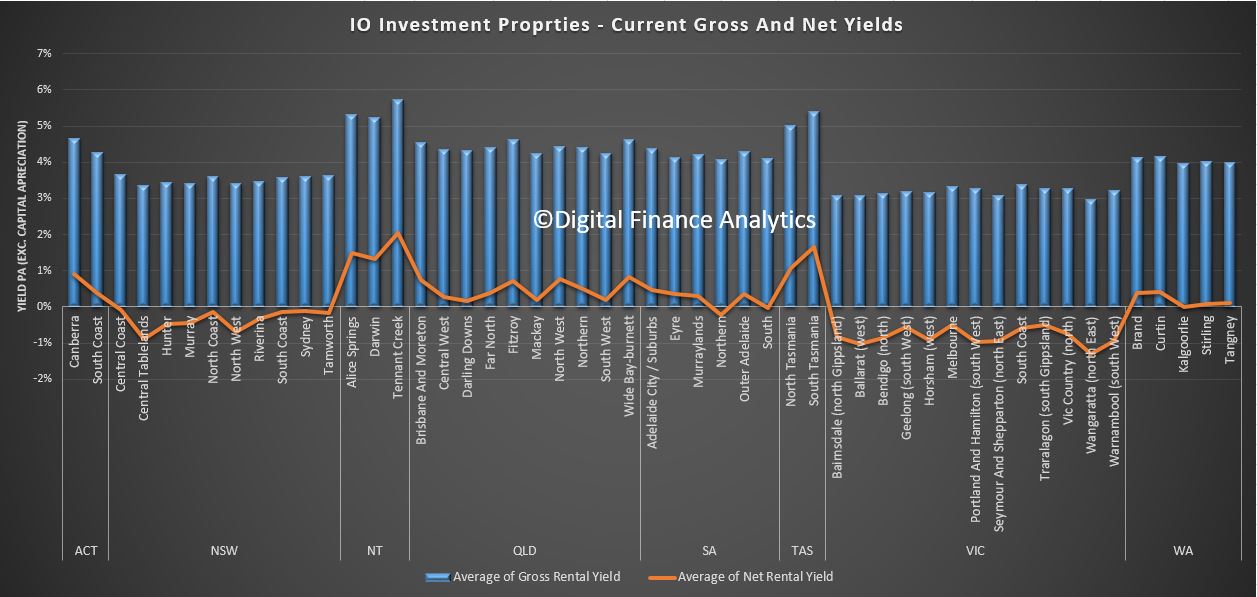

To the customer, interest-only is an attractive proposition for a number of reasons, from freeing up cash to tax incentives. Additionally, investors have widely financed rental property investments on an IO basis while paying down their owner-occupied P&I loan. Executive director of The Local Loan Company, Ray Hair, observes that it’s a decades-long trend, one that has taken place right under the radar of regulators and banks.

To date, availability has largely driven demand for IO, but with many borrowers now preparing to face the consequences of their honeymoon financial planning, a mounting collection of horror stories could change that.

“Whenever regulators initiate corrective action in a market there is an initial period of over correction, however the pendulum generally swings back to a position of equilibrium. Sadly, this is of little comfort to those caught out by the overnight changes in policy, increased interest rates and institutional disregard for the personal cost,” says Hair.

“Expect to see some very angry investors looking for a lender, broker or adviser to blame, and pay compensation” Ray Hair, The Local Loan Company

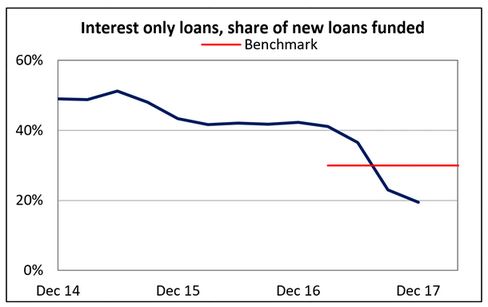

Major lenders are preparing their broker networks for further changes to lending criteria, and are actively assessing the terms of loans due to expire to 2022. But with many below the cap and borrowers looking for IO products, the call to return to business as (almost) usual has been too strong to resist.

“We have seen several major lenders loosen the reigns and cut the rates for interest-only loans again, likely because they are sitting below the cap and are looking to add more interest-only loans to their books. It will be interesting to observe whether other lenders follow and how this plays out in terms of consumer behaviour,” says Uno Home Loans CEO Vincent Turner.

The mortgage crunch

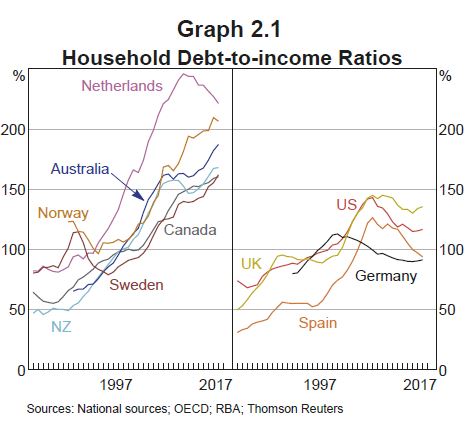

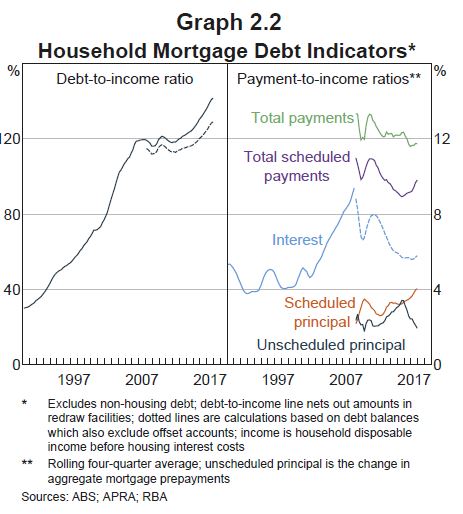

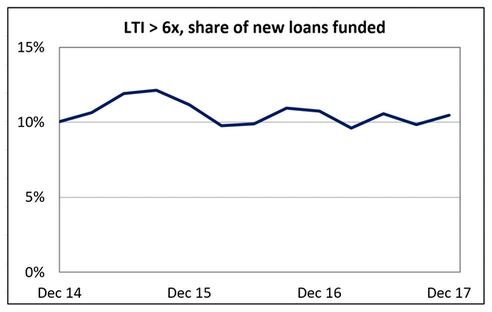

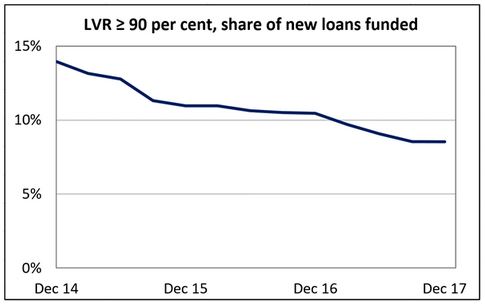

In January, UNSW professor of economics Richard Holden published a sobering observation of Australia’s relationship with high-LVR and IO loans. In it he reported Australian banks lend an average 25% more than their US counterparts and that these loans are poorly structured and sometimes based on falsified or inaccurate household finances.

.PNG)

A decade ago, US banks learned this lesson the hard way, when five-year adjustable rate mortgages could not be refinanced and the fallout triggered a chain reaction that dragged most of the globe into recession.

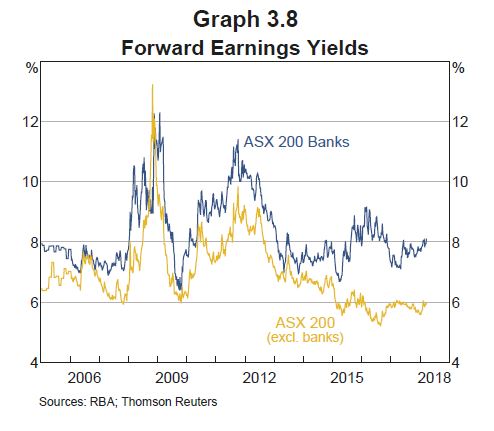

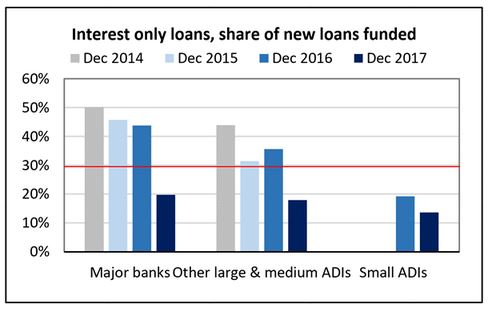

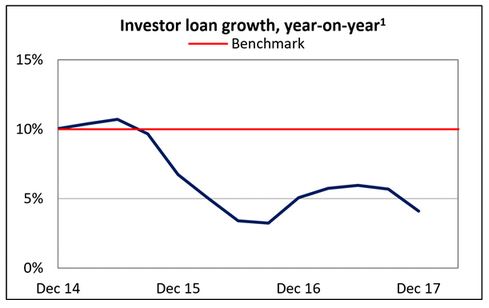

In Australia, IO lending has comprised as much as 40% of the loan book at the major banks, and a particularly large share of property investors choose IO. The number of new IO loans is in overall decline, $156bn borrowed in 2015 to $135.5bn in 2017, but their share is still significant. In the owner-occupier market they count for one in four loans, and in the investor market it’s two in three.

“Interest-only loans in Australia typically have a five-year horizon and to date have often been refinanced. If this stops then repayments will soar, adding to mortgage stress, delinquencies, and eventually foreclosures,” Holden told Australian Broker at the time.

“It’s our professional and ethical obligation to look after the best interests of our clients and help them plan strategies” Louisa Sanghera, Zippy Loans

A teacher at the University of Chicago when the US housing market crashed, he added, “The high proportion is similar to the high proportion of adjustable rate mortgages in the US circa 2007.”

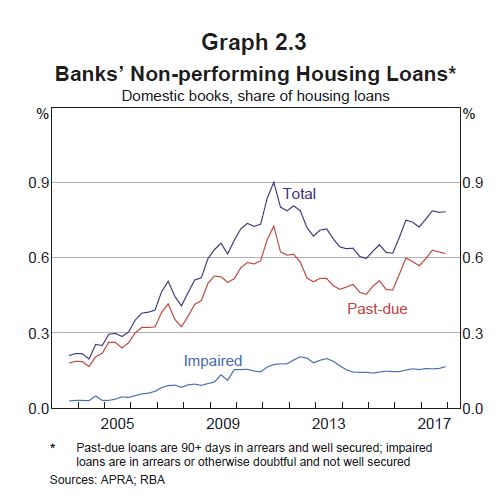

So how scared should people be? According to Hair, a lot of people “should be very afraid”, although he says dynamic lending policies, a banking sector unwilling to lose market share and strength in non-bank lenders will dampen some impact.

Quoting the DFA data, he adds, “Unfortunately, there will be pain for highly leveraged borrowers with negative equity, as there has been in the past with an oversupply of apartments, restrictions on non-resident lending and the fall

in property values in mining-dependent regional towns.”

For Turner, the concerns are overstated on a macro level, and reasonable lead times for a switch are all most borrowers will need. However, he warns, “The bigger concern should always be unemployment that triggers substantial hardship, very quickly across a broad group of people, which has the effect of contagion.”

Hero or villain?

While there are many unknowns in how borrowers and lenders will cope with the switch to P&I, what is known is that brokers could find themselves very busy between now and 2022.

“It’s our professional and ethical obligation to look after the best interests of our clients and help them plan strategies that are sustainable and supportive of their personal financial goals,” says Sanghera, who predicts a “positive impact overall” for brokers.

At Zippy Loans active management of IO customers means the lender has very few of the loans on its books. Responding to the rises in interest rate charges over recent months, Zippy has contacted its IO clients to move them onto a workable P&I solution.

“Clients will need to consider a broader range of lending options to find a product that works for them and brokers are ideally placed to research these options on their behalf. I believe this will result in more people turning to brokers to navigate the ever-more complex market place and secure the right solution,” she adds.

Throughout this process, transparency will be key, as Turner notes, “Brokers who continue to push expensive interest-only loans will probably lose business to those who show their customers when P&I works and when IO is the better option. In most cases it isn’t.”

However, brokers will also be the bearers of bad news as some are forced to sell and, according to Hair, it’s likely a lot of disgruntled borrowers will pursue their brokers in the courts, as many have done before when things have not gone their way.

Advising brokers to keep “well documented notes” of original transactions and borrower objectives, as well as subsequent attempts to refinance, he says: “Brokers will be both the heroes and the villains in this pantomime.”

“Expect to see some very angry investors looking for a lender, broker or adviser to blame, and pay compensation, for the position they find themselves in,” he adds.

Is this Australia’s sub-prime crisis? From those in the industry it’s a unanimous no. However that doesn’t mean to say a significant number of borrowers won’t receive a harsh wake-up call.

“The bigger concern should always be unemployment that triggers substantial hardship … which has the effect of contagion” Richard Holden, UNSW

For Holden, the damage has already happened and recent measures are too little too late. Although he refers to tighter lending standards as “comforting”, he says the 30% cap is “about all that can be done” at this point.

Australia’s smaller lenders lack the resources to manage more of the IO debt burden, meaning a mass exodus of customers away from the majors is unlikely. That doesn’t mean to say the majors won’t step up to the potential competition. As Hair predicts,

this could bring some attractive offers for borrowers looking to switch or refinance.

For now, it’s all eyes on the interest rate. On the one hand, no change in the cash rate for 19 months has manufactured a level of stability, on the other it’s delayed the hangover. The IMF has already advised implementation of US-style signalling for potential hikes, although after the last month there is some way to go before reaching the 4% rate it expects to see by late 2019.

Regardless of what happens, some pockets of stress are expected.

Within the industry, brokers have a chance to step up and guide customers through the uncertainties, but the watchful eyes of the regulators will be on them.

A $100bn question remains: how wealthy is the average Australian borrower? Those writing the rulebook say wealthy enough to cover higher mortgage payments. Those who have seen the cycle play out elsewhere, say otherwise.

.PNG)