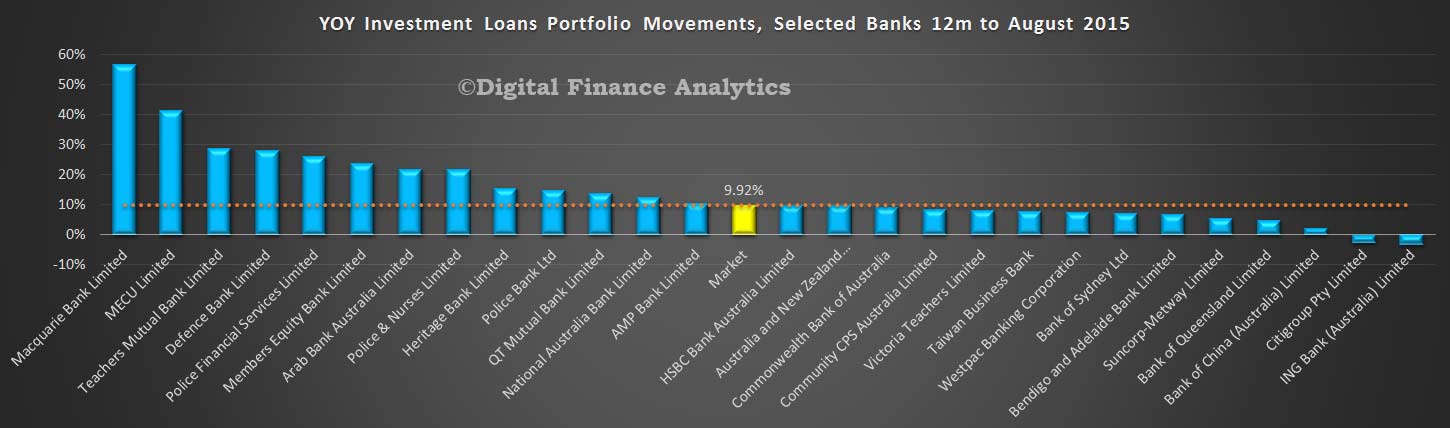

An interesting FOI disclosure from the RBA tells us something about the discussions which went on within the regulators in 2014 and beyond, as they considered the impact of the rise in investor loans. Eventually of course APRA set a 10% speed limit, and we have see the growth in investment loans slow significantly and underwriting standards tightened.

Back then, they discussed the risks of investment lending rising, especially in Melbourne.

Macroeconomic: Extra speculative demand can amplify the property price cycle and increase the potential for prices to fall later. Such a fall would affect household spending and wealth. This effect is likely to be spread across a broader range of households than the investors that contributed to the heightened activity.

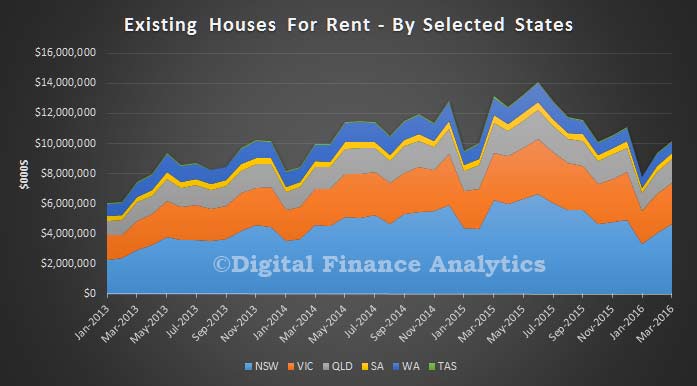

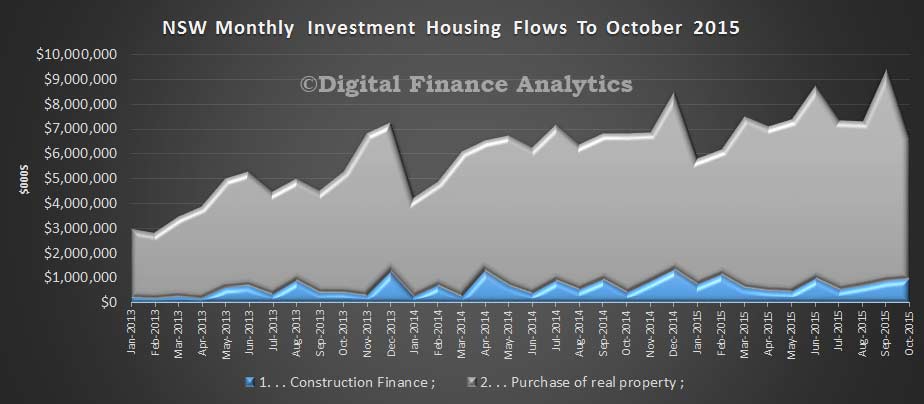

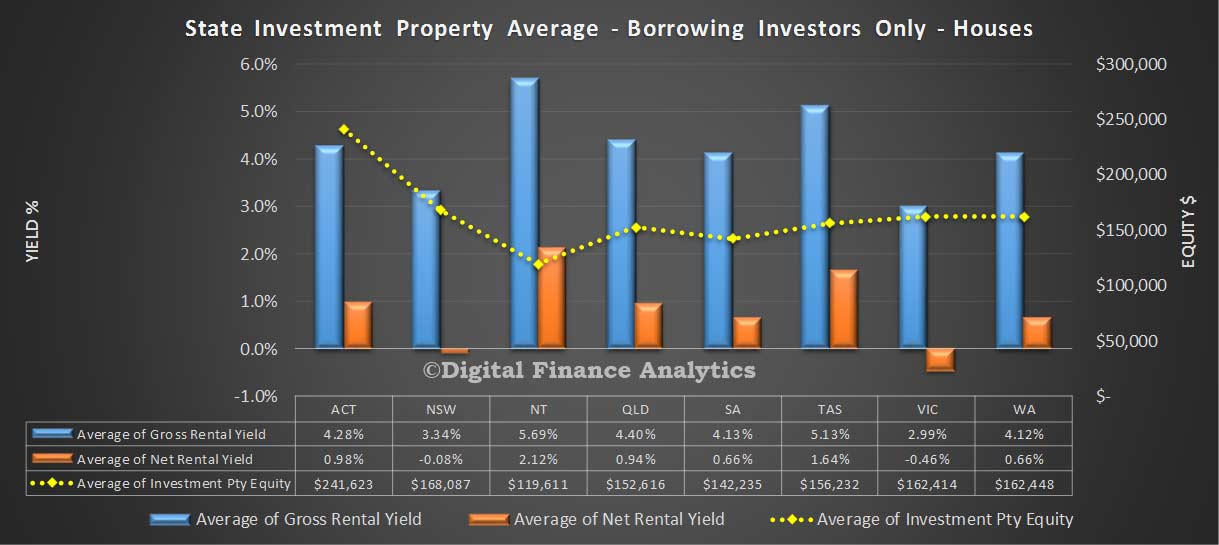

Concentration risk: Lending has been concentrated in Sydney and Melbourne, creating a concentrated exposure in these cities. The risk could come from a state-based economic shock, or if the speculative upswing in demand brings forth an increase in construction on a scale that leads to a future overhang of supply. In Sydney, the risk of oversupply appears limited because of the pick-up in construction follows a period of limited new supply and it has been spread geographically and by dwelling type. While the unemployment rate has picked up a little over the past 18 months, the overall economic environment in NSW is in a fairly good state. In Melbourne, there has been a greater geographic concentration of higher-density construction in inner-city areas. Some developments have a concentration of smaller-sized apartments that may only appeal to some renters, or purchasers in the secondary market. Economic conditions are not as favourable in Victoria and the unemployment rate is 6.8%.

Low interest rate environment: While a pick-up in risk appetite of households is to some extent an expected outcome given the low interest rate environment, their revealed preference is to direct investment into the housing market. Historically low interest rates (combined with rising housing prices and strong price competition in the mortgage market) means that some households may attempt to take out loans that they would not be able to comfortably service in a higher interest rate environment. APRA’s draft Prudential Practice Guide (PPG) emphasises that ADIs should apply an interest rate add-on to the mortgage rate, in conjunction with an interest rate floor in assessing a borrower’s capacity to service the loan. In order to maintain the risk profile of borrowers when interest rates are declining, the size of the add-on needs to increase (or the floor needs to be sufficiently high).

Lending standards: In aggregate, banks’ lending standards have been holding fairly steady overall; lending in some loan segments has eased a little, while lending in some other segments has tightened up a bit. The main lending standard of concern is the share of interest-only lending, both to owner-occupiers and investors. For investors, 64% of banks’ new lending is interest-only loans and for owner-occupiers the share is 31%. The typical interest-only period is 5 years, but some banks allow the interest-only period to extend to 15 years. During this period, the loan is amortising more slowly than a loan that requires principal and interest (P&I) payments. If housing prices should fall, this increases the risk that the loan balance may exceed the property value (negative equity). There is some risk that the borrower could face difficulty servicing the higher P&I payments when the interest-only period ends, although this is typically mitigated by banks assessing interest-only borrowers on their ability to make P&I payments.

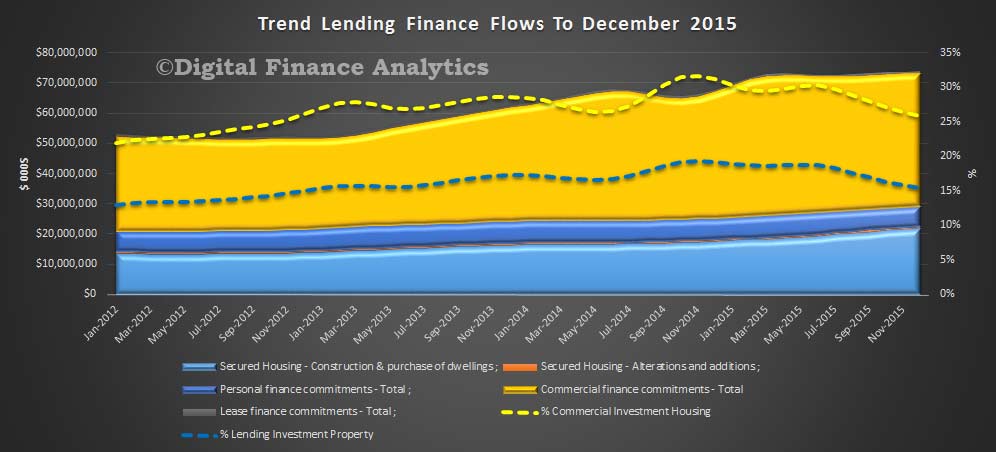

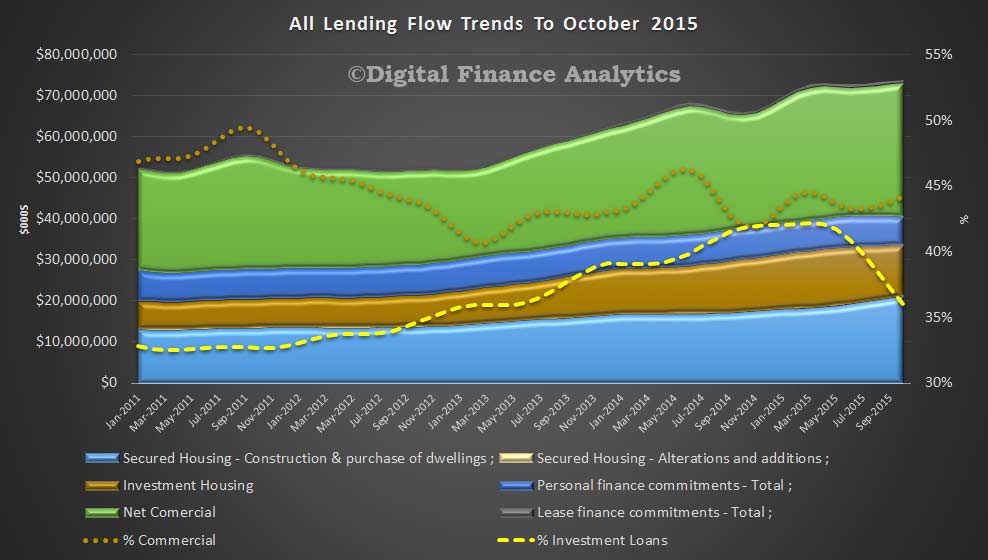

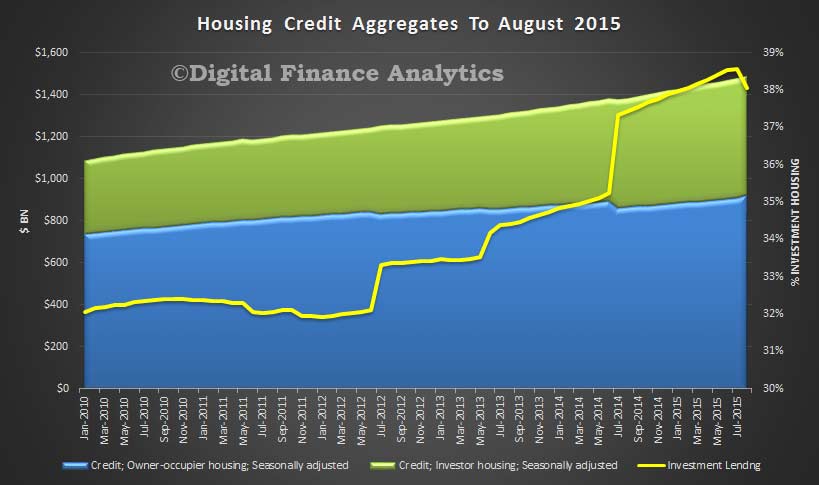

Of course the regulators found underwriting standards were more generous than they thought, at times in 2015 more than half of all new loans were investment loans, and recently banks have reclassified loans, causing the absolute proportion of investment loans to rise. Things were whose than they thought.

Next they discussed how to set the “right” growth rate:

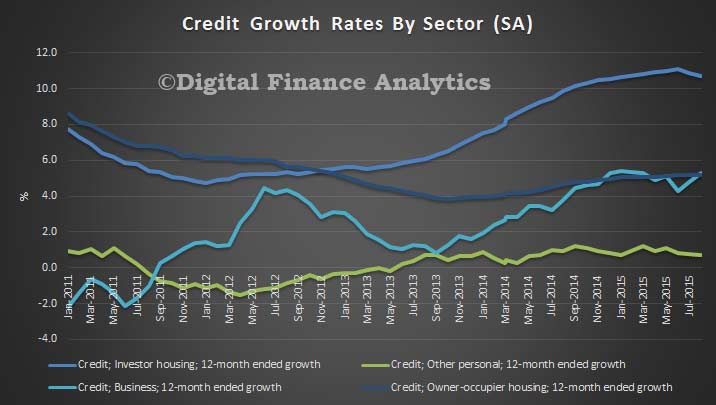

How to calibrate the benchmark growth rate? Household debt has been broadly stable as a share of income for about a decade. National aggregate ratios are not robust indicators of a sector’s resilience because the distribution of debt and income can change over time. But as a first pass, it is reasonable to expect that the current level of the indebtedness ratio is sustainable in a range of macroeconomic circumstances. Therefore there does not seem to be a case to set the benchmark growth rate significantly below the rate of growth of household income, in order to achieve a material decline in the indebtedness ratio. With growth in nominal household disposable income running at a little above 3 per cent, this sets a lower bound for possible benchmarks at around 3 per cent. Current growth in investor credit, at nearly 10 per cent, suggests an upper bound around 8 per cent to achieve

some comfort about the leverage in this market. Within this range, there are several options for the preferred benchmark rate for investor housing credit growth (including securitised credit).

a) Around 4½ per cent, based on projected household disposable income growth over calendar 2015. This could be justified as being consistent with stabilising the indebtedness ratio. However, it would be procyclical, in that it would be responding to a period of slow income growth by insisting that credit growth also slow. It would also be materially slower than the current rate of owner-occupier credit growth, which so far has not raised systemic concerns.

b) Around 6 per cent, based on a reasonable expectation of trend growth in disposable income, once the effects of the decline in the terms of trade have washed through. It is also broadly consistent with current growth in owner-occupier housing credit, which as noted above has not been seen as adding materially to systemic risk.

c) 7 per cent, consistent with the system profile for residential mortgage lending already agreed as part of the LCR/CLF process. Unless owner-occupier lending actually picks up from its current rate, however, the growth in investor housing credit implied by the CLF projections would be stronger than this. It is therefore not clear that these projections should be the basis for the preferred benchmark.

Staff projections suggest that only a moderate decline in system investor loan approvals would be required to meet a benchmark growth rate for investor housing credit in the 5–7 per cent range for calendar 2015. The exact size of the decline depends partly on assumptions about repayments through churn, refinancing and amortisation in the investor housing book. For a reasonable range of values for this implied repayment rate, and assuming that investor housing credit growth remains at its current rate for the remainder of 2014, the required decline in investor approvals is of the order of 10–20 per cent. This would take the level of investor housing loan approvals back to that seen a year ago. It is worth noting that investor loan approvals would have to increase noticeably from here to sustain the current growth rate of investor housing credit, even though the implied repayment rate is a little below its historical average. Since credit is not available at a state level, the benchmark can only be expressed as a national growth rate. The flow of loan approvals at a state level can be used as a cross-check to ensure that the benchmark incentive has had its greatest effects in the markets that have been strongest recently.

When the 10% cap (note this is higher than those bands discussed above) was announced, some Q&A’s provide some insights into their thinking.

Isn’t 10 per cent a bit soft? We are not trying to kill the market stone dead. Investor housing credit is currently running at a bit under 10 per cent. Some lenders will have investor credit growth well below this benchmark anyway, so if all lenders do end up at least a little under this benchmark, which we hope they will, then aggregate growth in investor credit will be noticeably below 10 per cent. Setting a benchmark for individual institutions is not the same thing as setting it for an aggregate, and APRA has allowed for that.

Where did the 10 per cent benchmark come from? This was a collective assessment by the Council agencies. We took the view that we did not want to clamp down on the market excessively. We also took the view that in the long run, household credit can expand sustainably at a rate something like the rate of trend nominal household income growth, maybe a bit more or less in shorter periods. Trend income growth is below 10 per cent, more like 6 per cent or thereabouts. But it was important to make an allowance for the fact that some lenders will undershoot the benchmark, so the aggregate result will likely be slower than that.

But isn’t household income growth likely to be below average in the next few years, because of the end of the mining boom? Maybe, but we don’t want to be procyclical and clamp down on credit supply more when the economy growing below trend.

This of course confirms the regulators were wanting to use household debt as an economic growth engine (interesting, see the recent post “Why more-finance-is-the-wrong-medicine-for-our-growth-problem” )

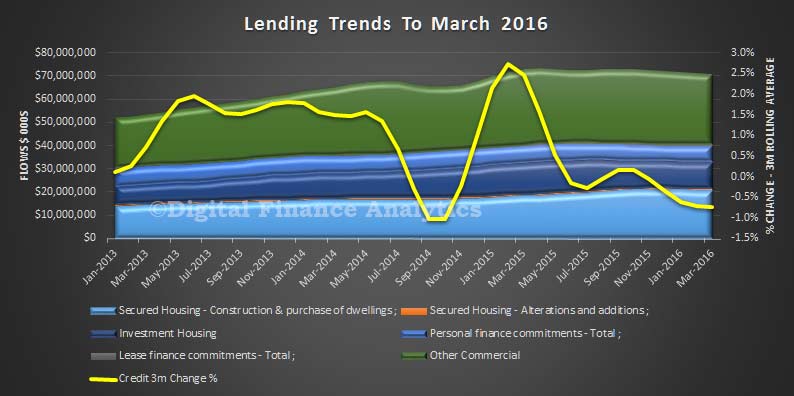

We also see a significant slow down in household income growth, yet credit growth, especially housing has been stronger, creating higher risks if interest rates or unemployment was to rise. Raises the question, were the regulators too slow to act, and did they calibrate their interventions correctly? We will see.

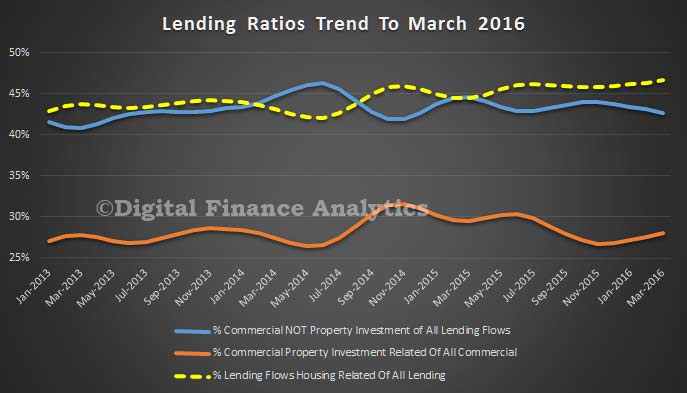

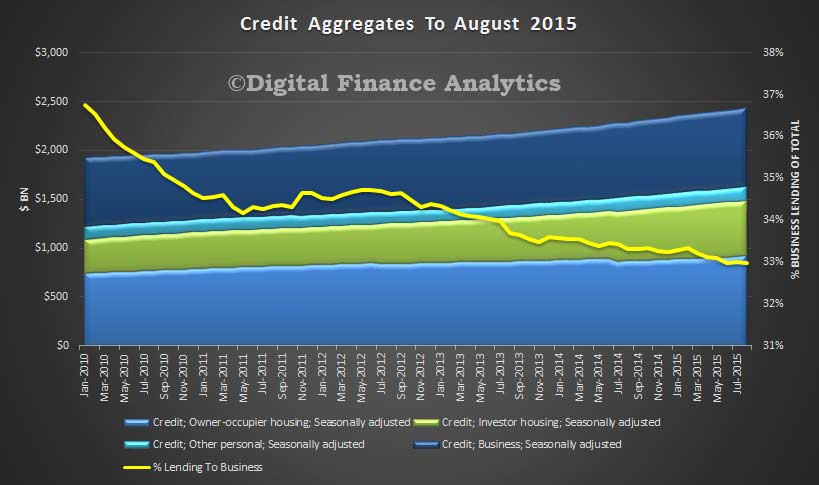

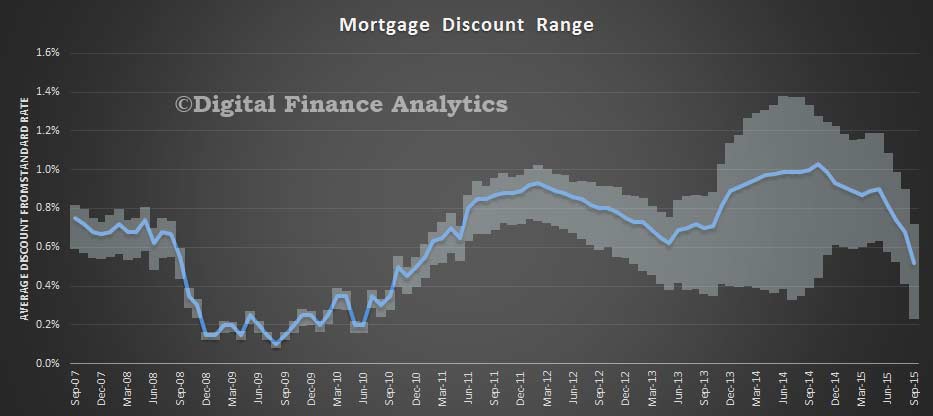

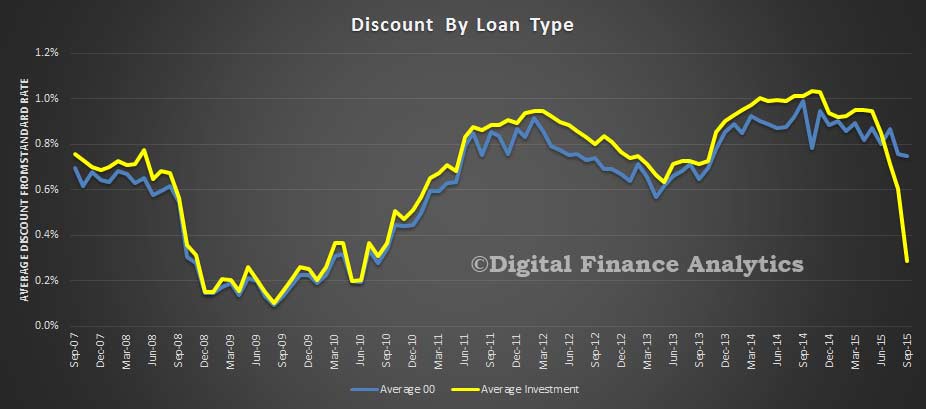

This is not a good outcome when lending to business can translate to productive growth, whilst lending for investment housing continues to stoke up home prices and bank balance sheets. No surprise the banks are cutting mortgage rates to try and attract more business, but at the expense of business lending.

This is not a good outcome when lending to business can translate to productive growth, whilst lending for investment housing continues to stoke up home prices and bank balance sheets. No surprise the banks are cutting mortgage rates to try and attract more business, but at the expense of business lending.