This week, it’s all about momentum – home prices are sliding, auctions clearance rates are slipping, mortgage standards are tightening and brokers are proposing to lift their business practices – welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly, to 16 December 2017.

Watch the video, or read the transcript. In this week’s edition we start with home prices.

Watch the video, or read the transcript. In this week’s edition we start with home prices.

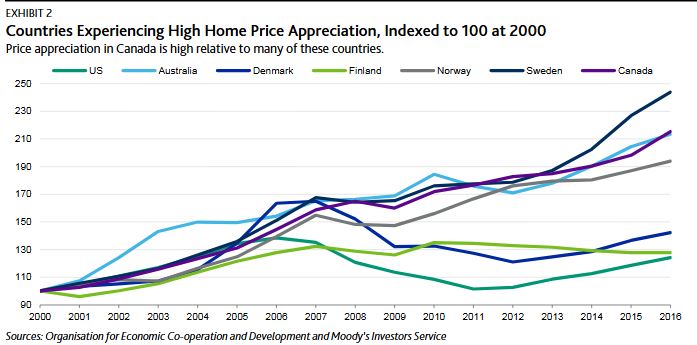

The REIA Real Estate Market Facts report said median house price for Australia’s combined capital cities fell 0.8 per cent during the September quarter. Only Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart recorded higher property prices and Darwin prices fell the most sharply, dropping 13.8 per cent.

The ABS Residential Property Price Index (RPPI) for Sydney fell 1.4 per cent in the September quarter following positive growth over the last five quarters. Hobart now leads the annual growth rates (13.8%), from a lower base, followed by Melbourne (13.2%) and Sydney (9.4%). Darwin dropped 6.3% and Perth 2.4%. For the weighted average of the eight capital cities, the RPPI fell 0.2 per cent and this was the first fall since the March quarter 2016. The total value of Australia’s 10.0 million residential dwellings increased $14.8 billion to $6.8 trillion. The mean price of dwellings in Australia fell by $1,200 over the quarter to $681,100.

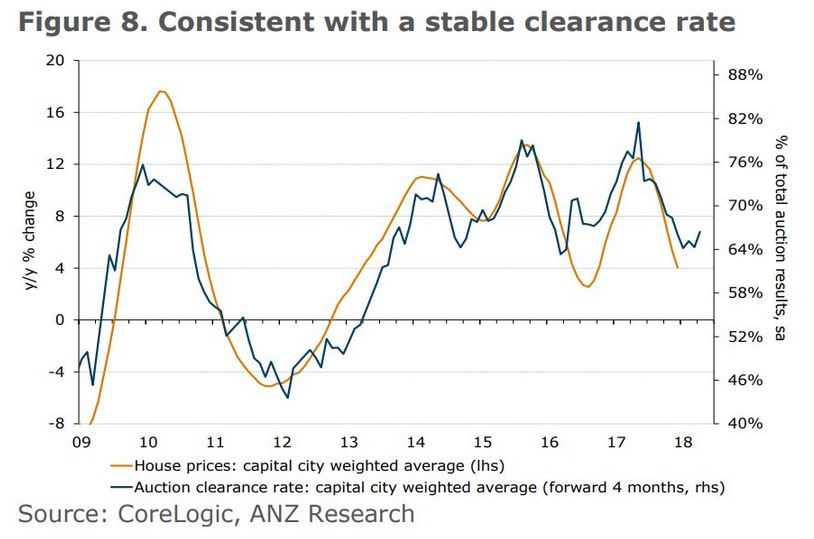

So, further evidence of a fall in home prices in Sydney, as lending restrictions begin to bite, and property investors lose confidence in never-ending growth. So now the question becomes – is this a temporary fall, or does it mark the start of something more sustained? Frankly, I can give you reasons for further falls, but it is hard to argue for improvement anytime soon. Melbourne momentum is also weakening, but is about 6 months behind Sydney. Yet, so far prices in the eastern states are still up on last year!

CoreLogic said continual softening conditions are evident across the two largest markets of Melbourne and Sydney. This week across the combined capital cities, auction volumes remained high with 3,353 homes taken to auction and achieving a preliminary clearance rate of 63.1 per cent The final clearance rate last week recorded the lowest not only this year, but the lowest reading since late 2015/ early 2016 (59.5 per cent).

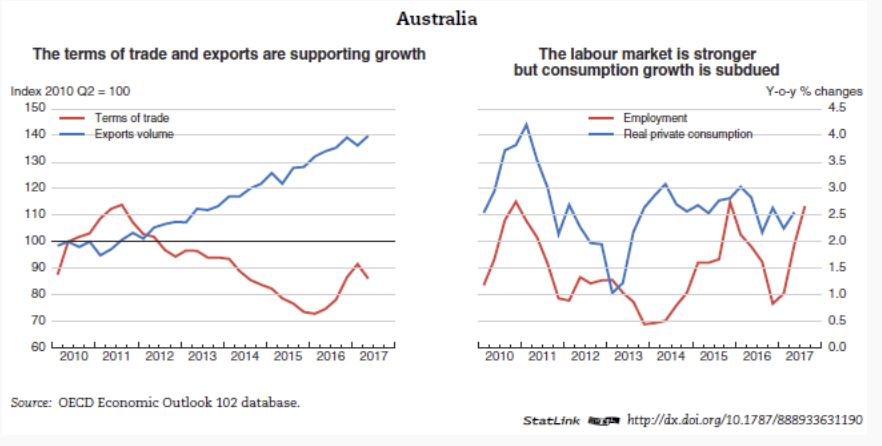

The employment data from the ABS showed a 5.4% result again in November. But there are considerable differences across the states, and age groups. Female part-time work grew, while younger persons continued to struggle to find work. Full-time employment grew by a further 15,000 in November, while part-time employment increased by 7,000, underpinning a total increase in employment of 22,000 persons. Over the past year, trend employment increased by 3.1 per cent, which is above the average year-on-year growth over the past 20 years (1.9 per cent). Trend underemployment rate decreased by 0.2 pts to 8.4% over the quarter and the underutilisation rate decreased by 0.3 pts to 13.8%; both still quite high.

The HIA said there have been a fall in the number of new homes sold in 2017. New home sales were 6 per cent lower in the year to November 2017 than in the same period last year. Building approvals are also down over this time frame by 2.1 per cent for the year. The HIA expects that the market will continue to cool as subdued wage pressures, lower economic growth and constraints on investors result in the new building activity transitioning back to more sustainable levels by the end of 2018.

The HIA also reported that home renovation spending is down, again thanks to low wage growth and fewer home sales by 3.1 per cent. A further decline of a similar magnitude is projected for 2018.

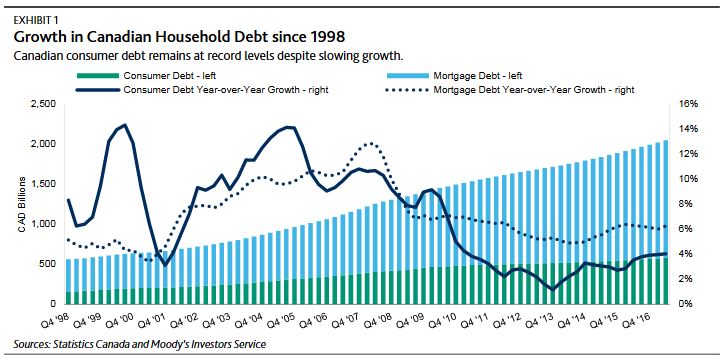

Moody’s gave an interesting summary of the Australian economy. They recognise the problem with household finances, and low income growth. They expect the housing market to ease and mortgage arrears to rise in 2018. They also suggest, mirroring the Reserve Bank NZ, that macroprudential policy might be loosened a little next year.

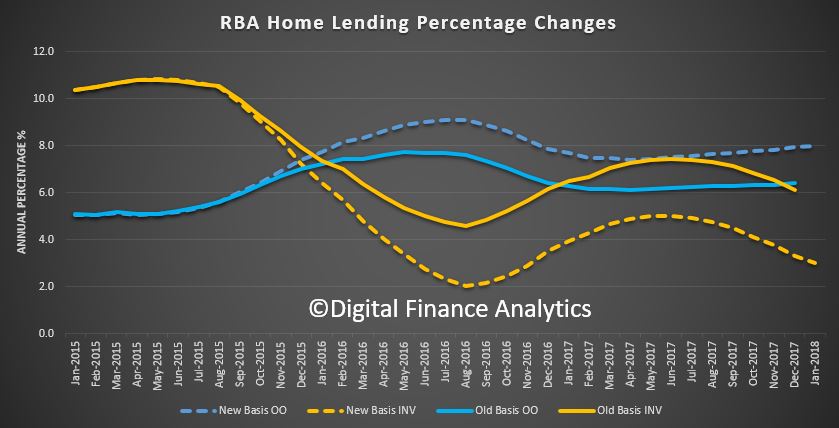

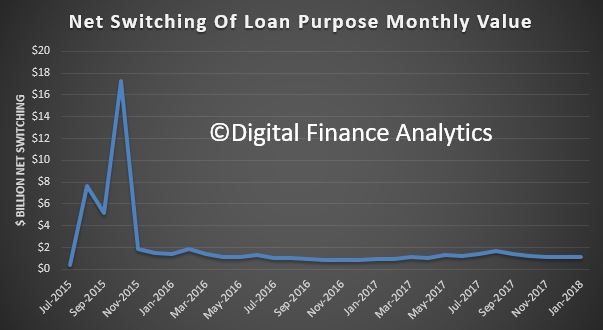

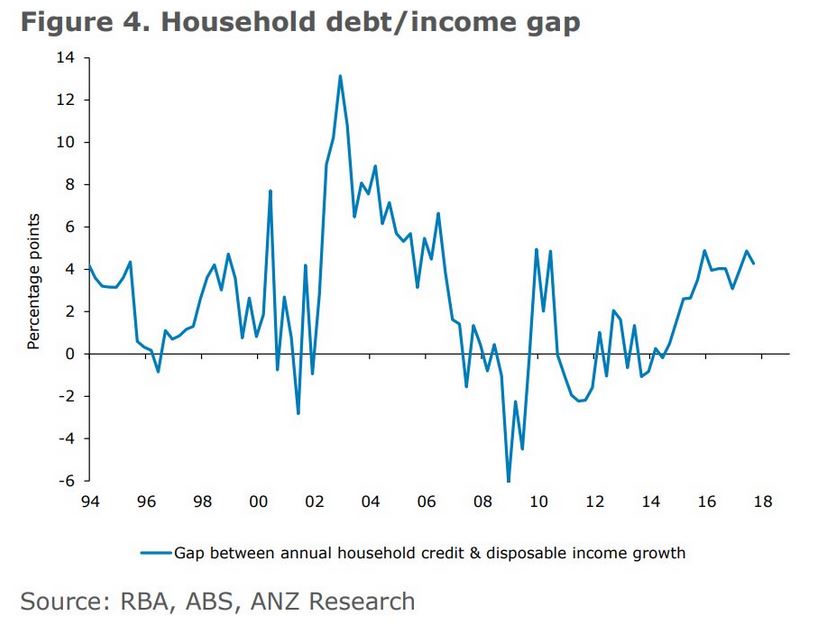

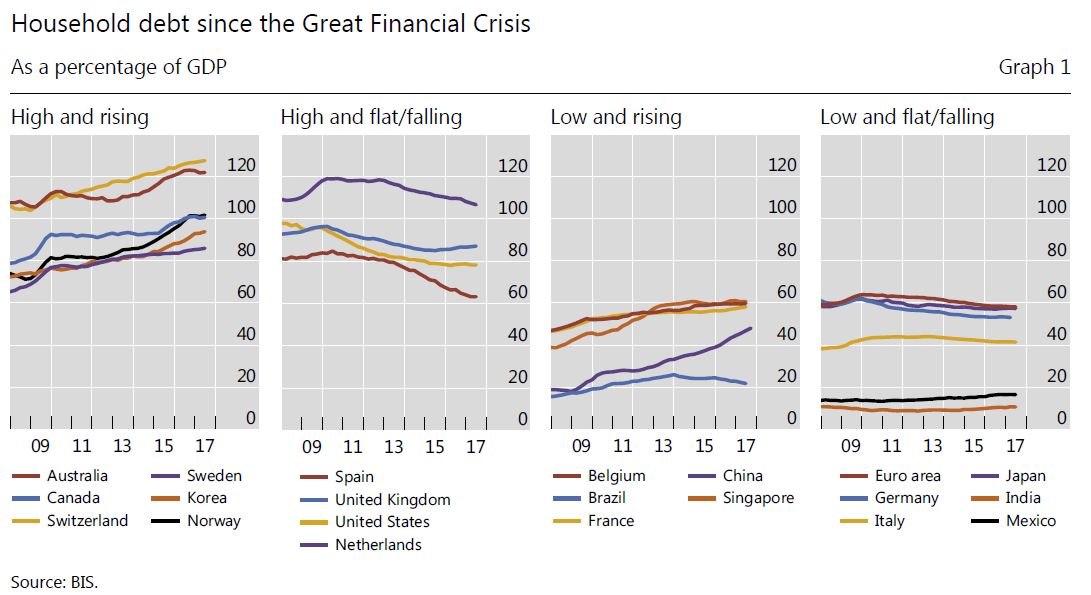

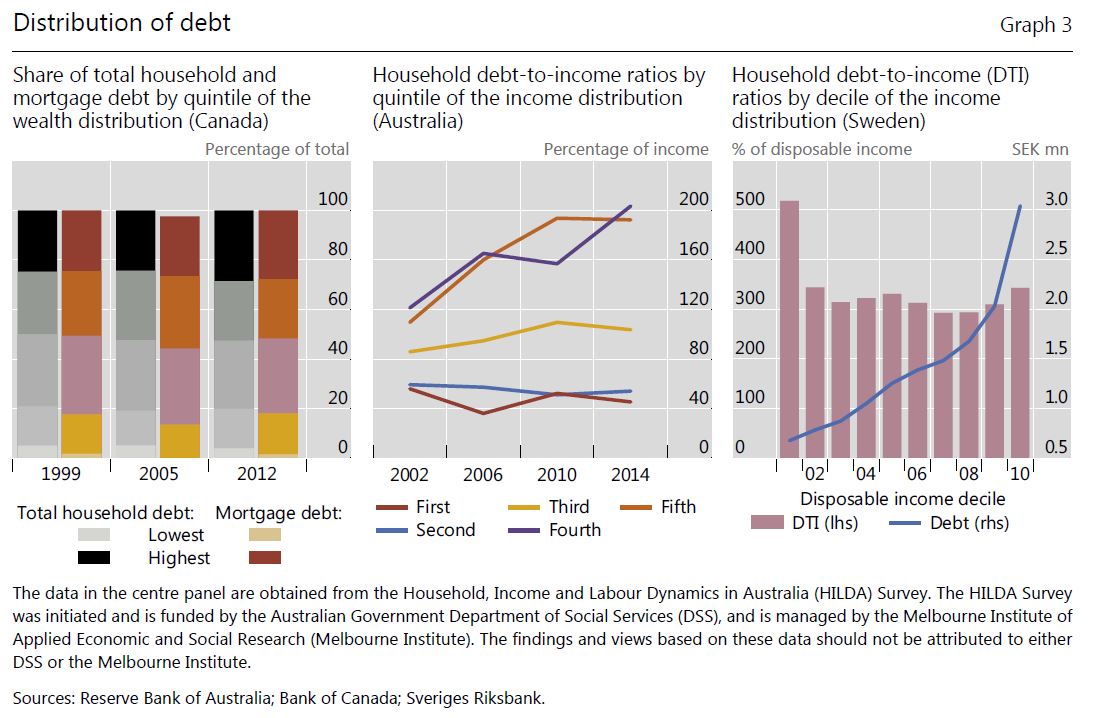

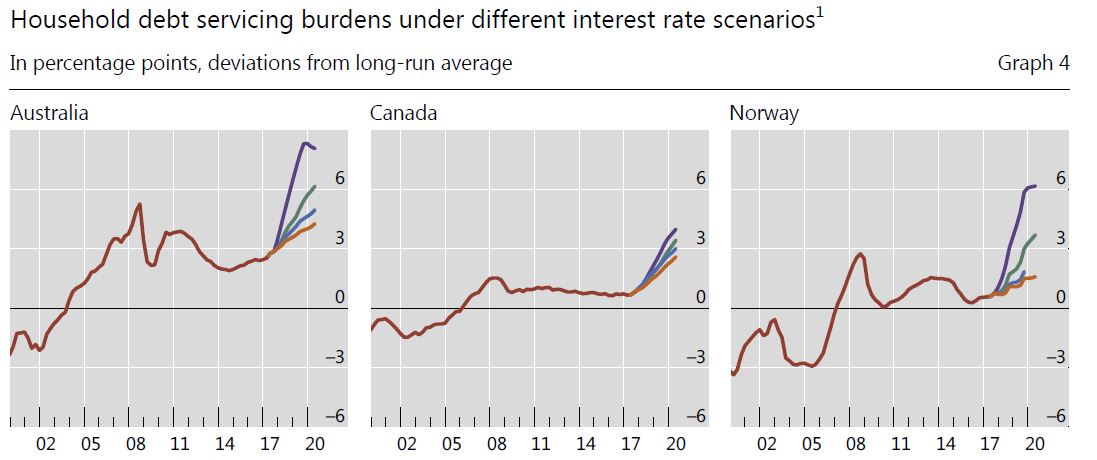

I have to say, given credit for housing is still running at three times income growth, and at very high debt levels, we are not convinced! I find it weird that there is a fixation among many on home price movements, yet the concentration and level of household debt (and the implications for the economy should rates rise), plays second fiddle. Also, the NZ measures were significantly tighter, and the recent loosening only slight (and in the face of significant political measures introduced to tame the housing market). So we think lending controls should be tighter still in 2018.

The latest ABS lending finance data for October, showed business investment was still sluggish, with too much lending for property investment, and too much additional debt pressure on households. If we look at the fixed business lending, and split it into lending for property investment and other business lending, the horrible truth is that even with all the investment lending tightening, relatively the proportion for this purpose grew, while fixed business lending as a proportion of all lending fell. I will repeat. Lending growth for housing which is running at three times income and cpi is simply not sustainable. Households will continue to drift deeper into debt, at these ultra-low interest rates. This all makes the RBA’s job of normalising rates even harder.

HSBC, among others, is suggesting a further fall in home price momentum next year, writing that slowdowns in the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets will continue to weigh on national house price growth for the next few quarters. They expect only a slow pace of cash rate tightening and some relaxation of current tight prudential settings as the housing market cools.

Despite this, most analysts appear to believe the next RBA cash rate move will be higher and ANZ pointed out with employment so strong, there is little expectation of rate cuts in response to easing home prices. In addition, the FED’s move to raise the US cash rate this week to a heady 1.5% despite inflation still running below target, will tend to propagate through to other markets later. More rate rises are expected in 2018. The Bank of England held theirs steady, after last month’s hike.

The UK Property Investment Market could be a leading indicator of what is ahead for our market. But in the UK just 15% of all mortgages are for investment purposes (Buy-to-let), compared with ~35% in Australia. Yet, in a down turn, the Bank of England says investment property owners are four times more likely to default than owner occupied owners when prices slide and they are more likely to hold interest only loans. Sounds familiar? According to a report in The Economist, “one in every 30 adults—and one in four MPs—is a landlord; rent from buy-to-let properties is estimated at up to £65bn a year. But yields on rental properties are falling and government policy has made life tougher for landlords. The age of the amateur landlord may be over”.

In company news, Genworth, the Lender Mortgage Insurer announced that it had changed the way it accounts for premium revenue. ASIC had raised concerns about how this maps to the pattern of historical claims. Genworth said that losses from the mining sector where many of the losses occur, do so at a late duration, and improvements in underwriting quality in response to regulatory actions, along with continued lower interest rates, extended the average time to first delinquency. As a result, Net Earned Premium (NEP) is negatively impact by approximately $40 million, and so 2017 NEP is expected to be approximately 17 – 19 per cent lower than 2016, instead of the previous guidance of a 10 to 15 per cent reduction.

CBA was in the news this week, with AUSTRAC alleging further contraventions of Australia’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing legislation. The new allegations, among other things, increase the total number of alleged contraventions by 100 to approximately 53,800. CBA contests a number of allegations but admit others. eChoice, in voluntary administration, has been bought by CBA via its subsidiary Finconnect Australia, saying the sale will allow eChoice’s employees, suppliers, brokers, lenders and leadership team to continue to operate and deliver for customers. Finally, CBA announced that, from next year, it will no longer accept accreditations from new mortgage brokers with less than two years of experience or from those that only hold a Cert IV in Finance & Mortgage Broking, in a move intended to “lift standards and ensure the bank is working with high-quality brokers who are meeting customers’ home lending needs.”

The Combined Industry Forum, in response to ASIC’s Review of Mortgage Broker Remuneration has come out with a set of proposals. The CIF defines a good customer outcome as when “the customer has obtained a loan which is appropriate (in terms of size and structure), is affordable, applied for in a compliant manner and meets the customer’s set of objectives at the time of seeking the loan.” Additionally, lenders will report back to aggregators on ‘key risk indicators’ of individual brokers. These include the percentage of the portfolio in interest only, 60+ day arrears, switching in the first 12 months of settlements, an elevated level of customer complaints or poor post-settlement survey results. Now this mirrors the legal requirement not to make “unsuitable” loans, but falls short of consumer advocates, such as CHOICE, who wanted brokers to be legally required to act in the best interests of consumers, in common with financial planners. But both the CBA and CIF moves indicate a need to tighten current mortgage broking practices, as ASIC highlighted, which can only be good for borrowers. By the end of 2020, brokers will also be given a “unique identifier number”.

ASIC says Westpac will provide 13,000 owner-occupiers who have interest-only home loans with an interest refund, an interest rate discount, or both. The refunds amount to $11 million for 9,400 of those customers. The remediation follows an error in Westpac’s systems which meant that these interest-only home loans were not automatically switched to principal and interest repayments at the end of the contracted interest-only period.

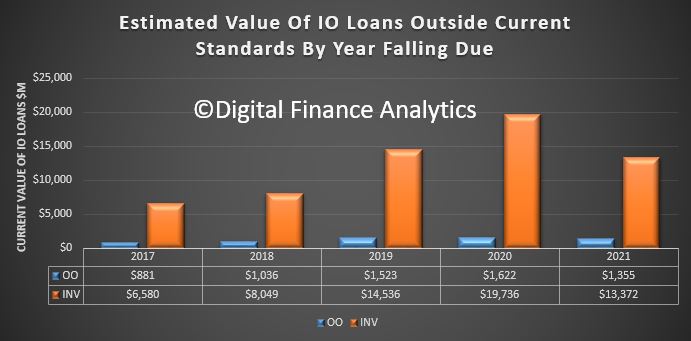

We featured a piece we asked Finder.com.au to write on What To Do When The Interest-only Period On Your Home Loan Ends. There is a sleeping problem in the Australian Mortgage Industry, stemming from households who have interest-only mortgages, who will have a reset coming (typically after a 5-year or 10-year set period). This is important because now the banks have tightened their lending criteria, and some may find they cannot roll the loan on, on the same terms. Interest only loans do not repay capital during their life, so what happens next?

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics released their third report on their Review of the Four Major Banks. They highlight issues relating to IO Mortgage Pricing, Tap and Go Debt Payments, Comprehensive Credit and AUSTRAC Thresholds. The report recommended that the ACCC, as a part of its inquiry into residential mortgage products, should assess the repricing of interest‐only mortgages that occurred in June 2017, and whether customers had been misled. While the banks’ media releases at the time indicated that the rate increases were primarily, or exclusively, due to APRA’s regulatory requirements, the banks stated under scrutiny that other factors contributed to the decision. In particular, banks acknowledged that the increased interest rates would improve their profitability.

So, in summary plenty of evidence home prices are slipping, and lending standards are under the microscope. We think home prices will slide further, and wages growth will remain sluggish for some time to come, so more pressure on households ahead. You can hear more about our predictions for 2018 in our upcoming end of year review, to be published soon, following the mid-year Treasury forecast.

Meantime, do check back next week for our latest update, subscribe to receive research alerts, and many thanks for watching.