Moody’s says Norway’s Proposed Tighter Mortgage Underwriting Standards Are Credit Positive for Banks and Covered Bonds.

On 8 September, Norway’s Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA) published a proposal for tighter mortgage underwriting limits. The proposed regulation, made to the Ministry of Finance, includes a limit of 5x loan value to the borrower’s gross income; requiring loans to amortise down to a 60% loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, down from 70%; a maximum home-equity LTV of 60%, down from 70%; and the reduction or complete elimination of banks’ ability to deviate by 10% from the regulatory limits, including the 85% maximum LTV requirement.

The new measures would reduce borrowers’ ability to take on excessive debt amid still-increasing house prices, particularly in the urban areas concentrated around the capital city of Oslo. These more restrictive proposals are credit positive and would strengthen the credit quality of mortgage loans on banks’ balance sheets and in covered bond cover pools.

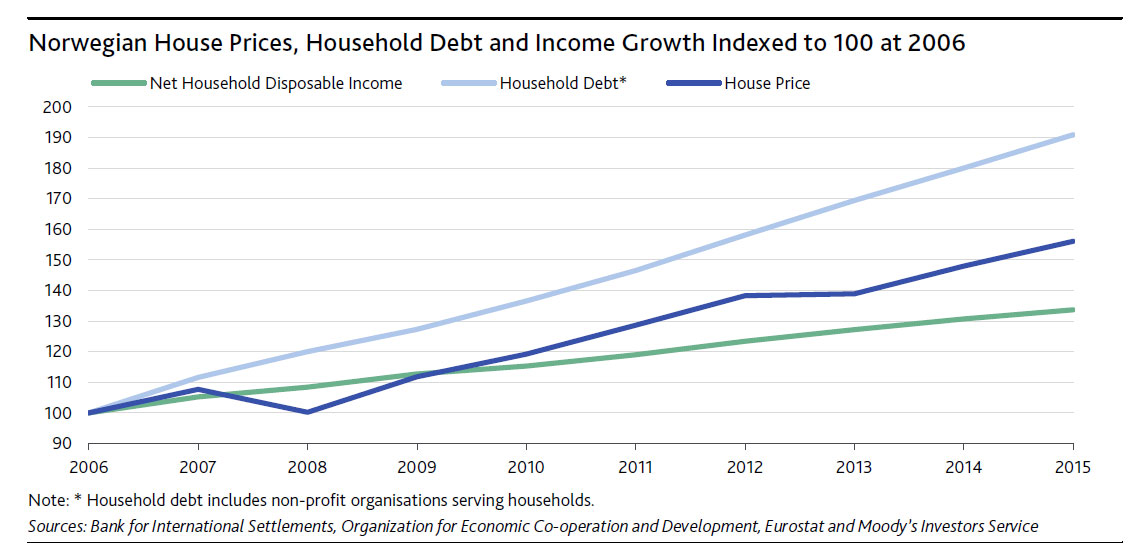

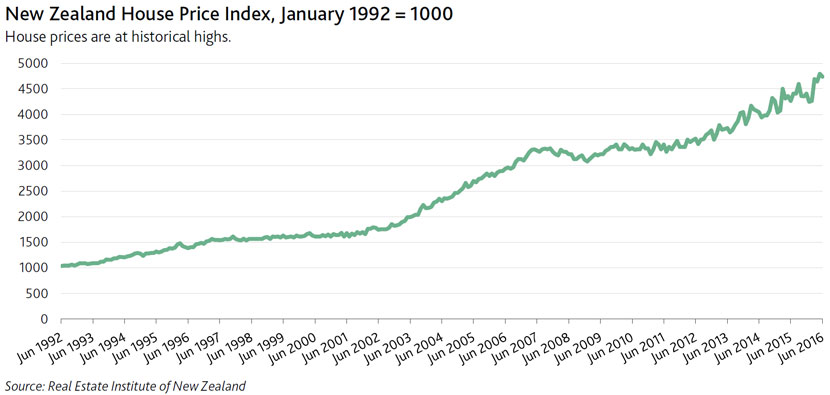

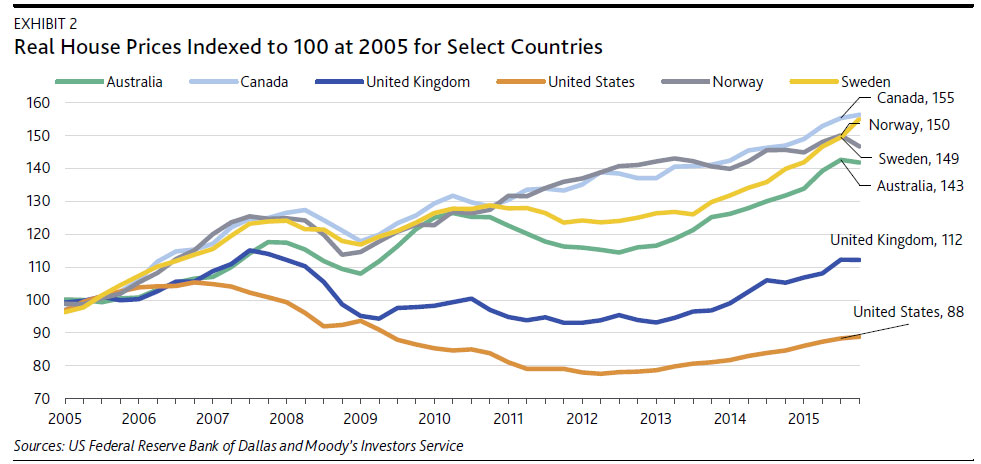

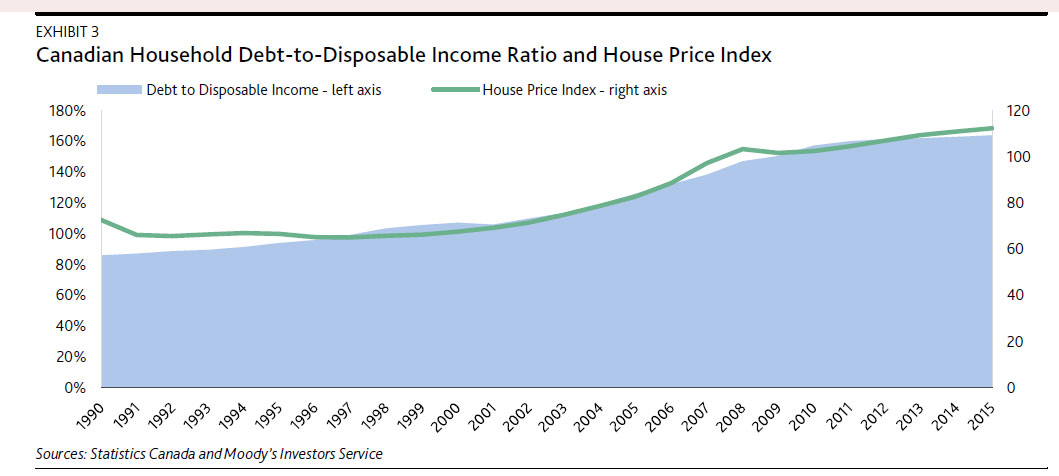

Norway has experienced strong house price growth since 2008 and the proposal for tighter regulations seeks to dampen excessive house price growth and credit expansion. Despite house price contraction in oilreliant areas such as Stavanger, prices in Oslo remain on a strong upward trajectory and increased more than 12% per year to the end of June. During the same period, banks and mortgage companies’ residential mortgage lending grew nationally by around 6%, according to Statistics Norway. Although Norwegian banks and covered bonds performed strongly even after the decline in oil prices, a mortgage market cool down would reduce the risk of asset price bubbles and excessive lending to vulnerable households.

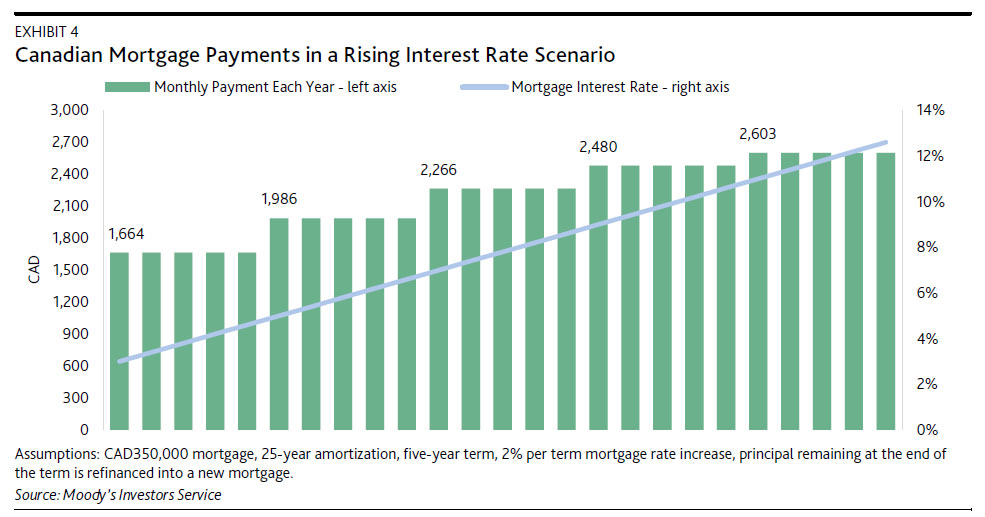

Capping the loan-to-income ratio limits the overall size of loan a borrower can take, regardless of affordability. In the present low interest rate environment, loan affordability is good, but large loans can easily become burdensome if interest rates rise. Lower LTV ratios decrease the loan’s probability of default and increase recoveries of loans that do default.

Increased amortization and limits on home-equity withdrawal reduce or constrain LTVs and limit potential payment shocks, benefiting mortgage loans’ credit quality. Currently, banks must factor amortisation into affordability testing, but a material proportion of loans are still interest-only. Interest-only loans can be vulnerable in a falling house price environment. Unlike an amortising loan, an interest-only loan’s LTV only declines over time as a result of house price appreciation, resulting in a potentially lower equity buffer against declining house prices and leaving the borrower exposed if selling the property is the only method of repaying the loan at maturity. Similarly, restricting home-equity withdrawals limits increases in LTVs and discourages borrowers from taking on high debt burdens.

Removing or reducing banks’ ability to have up to 10% of loans breach the maximum 85% LTV requirement or other requirements would be prudent. The FSA considers the 10% limit substantial in light of debt and house price developments. If the government does not completely remove the 10% waiver from the regulations, the FSA suggests reducing it to 4%.

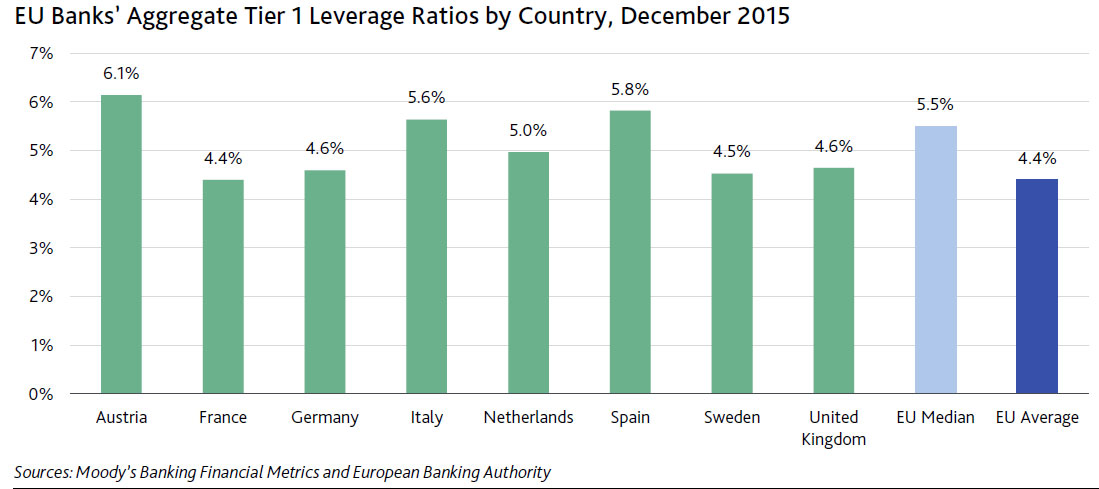

An advantage of having the regulator set underwriting restrictions is that it prevents competition from eroding prudent practices, while also allowing the rules to be changed when conditions warrant such changes. However, nationally applicable restrictions do not differentiate between Norway’s regions, and regional economic developments vary. The FSA emphasized that the tighter regulation may be temporary and could be lifted if market conditions changed, which would give banks the opportunity to recover some flexibility in their lending practices. Nevertheless, Norway’s underwriting standards and prudential regulation of mortgage loans are among the strongest in Europe, particularly the country’s conservative approach to LTVs and its affordability stress of five percentage points on loan interest rates.