We have just finished the December update of our mortgage stress and probability of default modelling for the Australian mortgage market.

Our model has been updated to take account of the latest employment, wage, interest rate and growth data, and we look are the current distribution of mortgage stress (can households settle their mortgage repayments, on time without financial pressure?) and make an estimate of the probability of households defaulting on their repayments by more than 30 days. The former uses our survey data on mortgages held, interest rates applied, and income available in the light of other financial commitments. Probability of default overlays the broader economic drivers. The base analysis is completed at a customer segment level by post code then rolled up to form various data views. In the next few days, we will discuss the findings in some detail. You can read more about our approach here. We also also reveal the current top 100 post codes for mortgage stress and mortgage defaults across the nation.

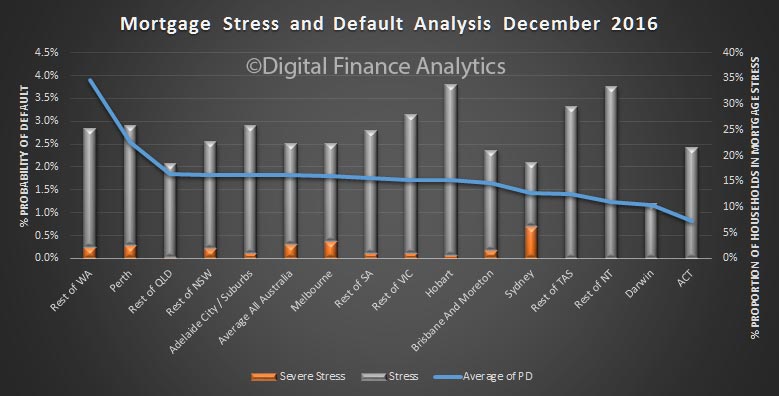

To begin, here is a summary by states, split down by CBD and rest of state.

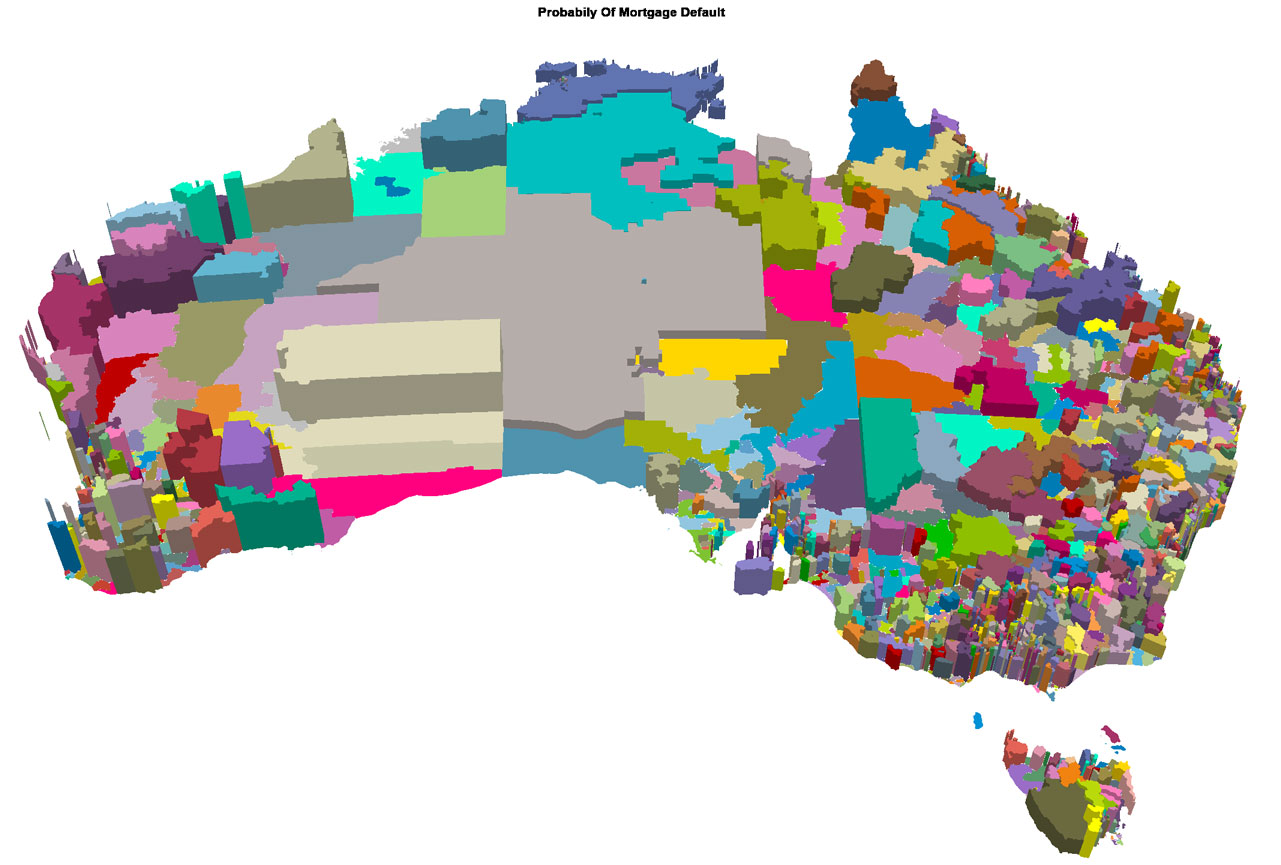

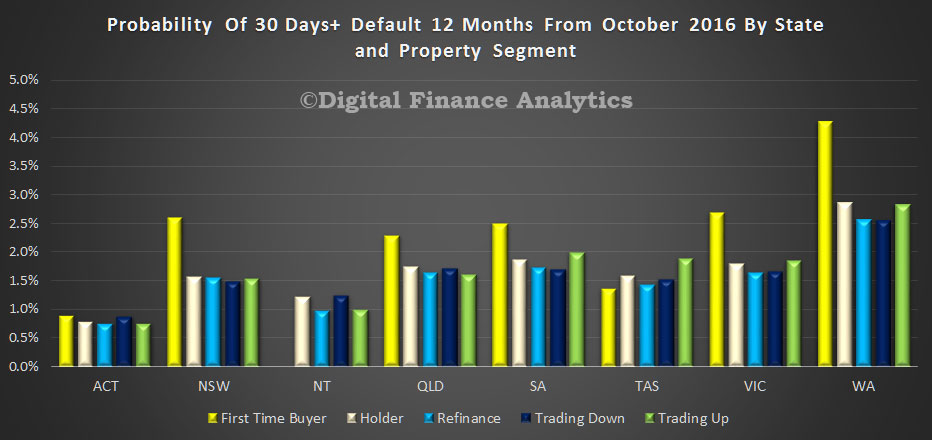

The highest probability of default can be found in regional WA, thanks to pressure in the mining belt. 30 days defaults will be close to 4%. Here, around 25% of households are in mortgage stress, including some in severe stress – see our descriptions here.

The highest probability of default can be found in regional WA, thanks to pressure in the mining belt. 30 days defaults will be close to 4%. Here, around 25% of households are in mortgage stress, including some in severe stress – see our descriptions here.

Default expectations are also high in and around Perth, where employment prospects are faltering, and incomes under pressure. In QLD, away from Brisbane, we see similar issues. The ACT has the lowest level of default probability.

The highest levels of mortgage stress are found in Tasmania, and across Regional NT, where more than 30% of households are under pressure. We also see hot spots in regional areas.

Of note is the high proportion of households in greater Sydney in severe mortgage stress – at 6.2% of borrowing households. This is a function of large mortgages (driven by high prices), rising interest rates AND flat incomes. By way of comparison, Melbourne households in severe stress sit at 3.3%, as mortgages are a little smaller. They are both higher than the national average of 2.8% of households.

Combined, across the country, more than 22% of all households are now in some degree of mortgage stress.

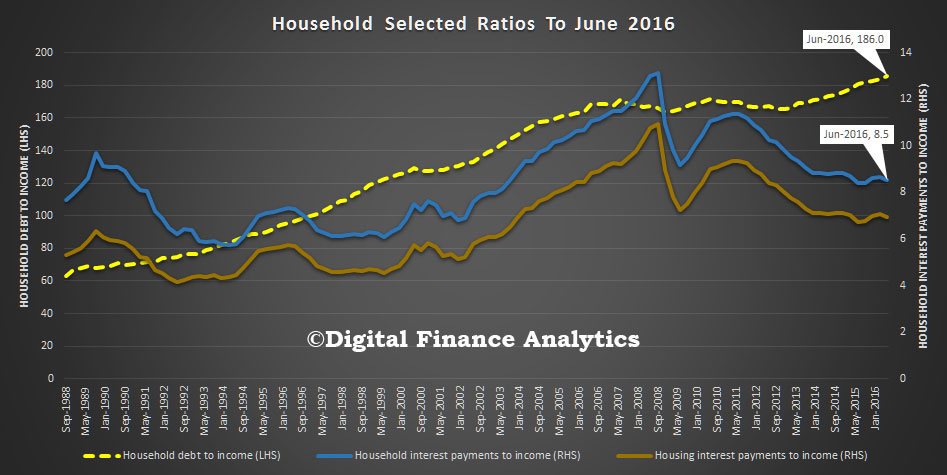

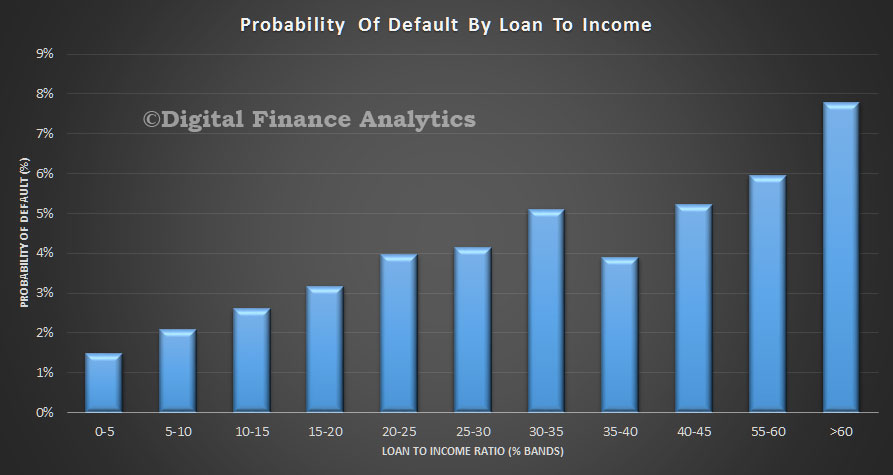

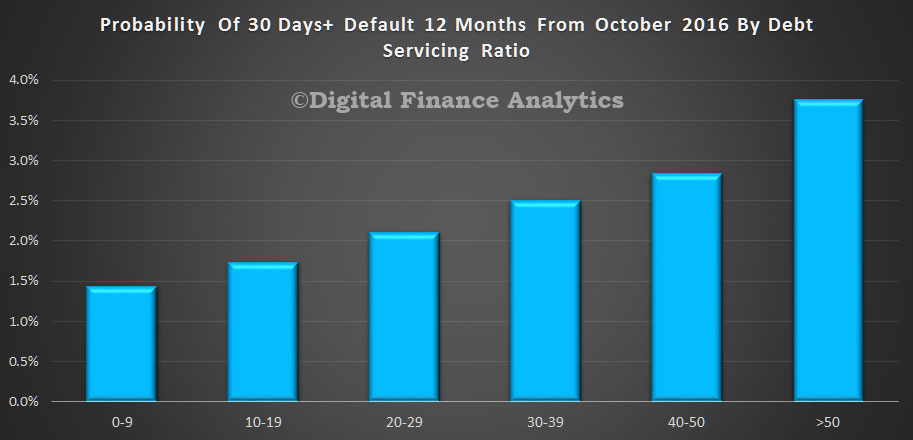

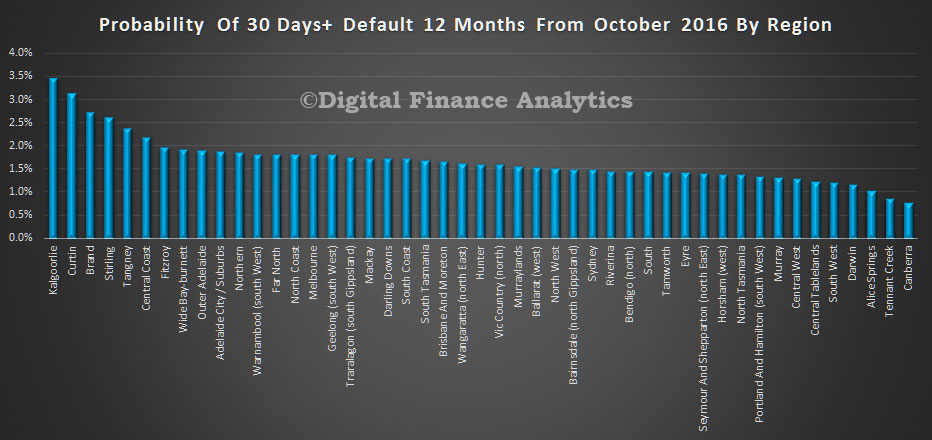

Next time we will dig into the more specific geographic footprints, because you really have to get granular to make sense of what is going on. Averages across the national simply mask what is going on. Later will will look at loan-to-income and debt servicing ratios which are also deteriorating for many. Then finally we will look at the loss implications for the banking sector.