On Tuesday, Canada’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) published the final version of “Guideline B-20 − Residential Mortgage Underwriting Practices and Procedures,” which mandates more stringent stress-testing for uninsured mortgages. The guideline, which takes effect on 1 January 2018 and applies to all federally regulated financial institutions in the country, is credit positive because it will improve asset quality for Canadian banks.

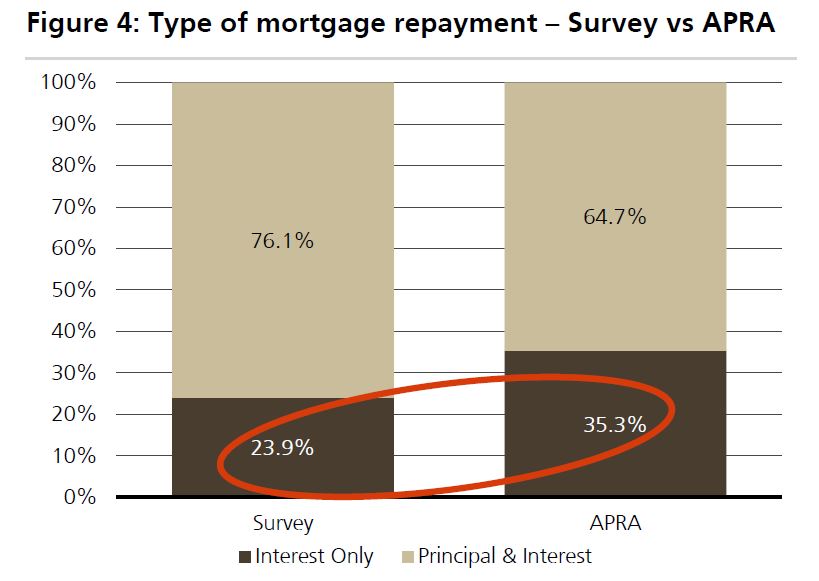

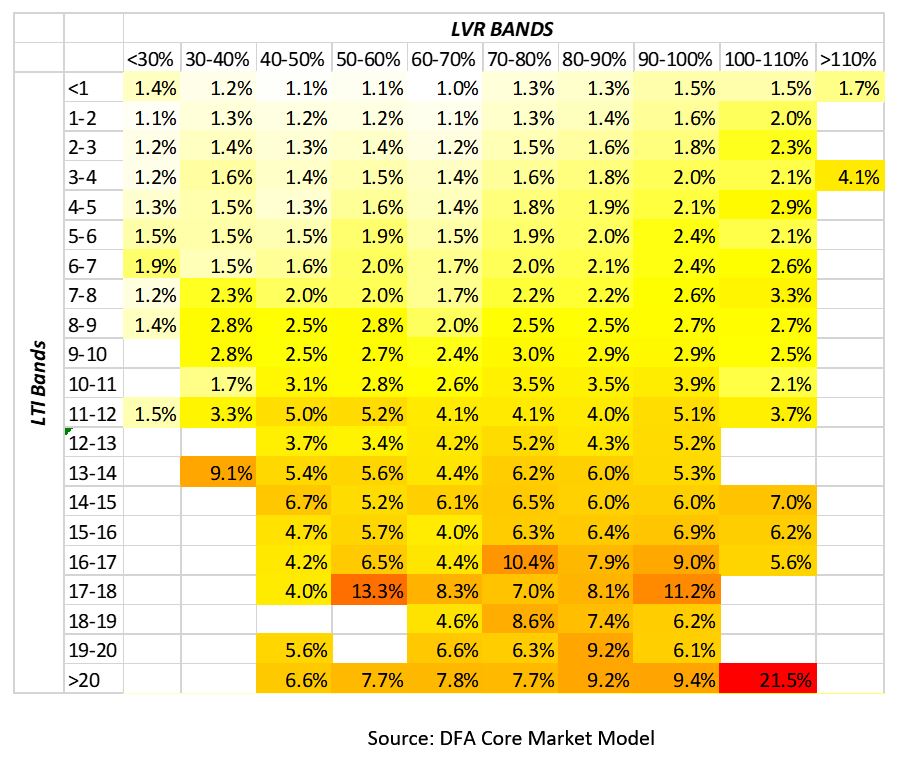

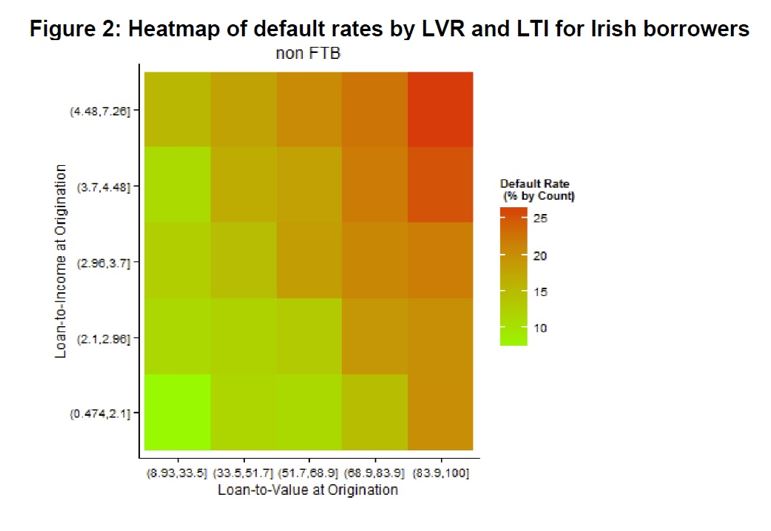

The guideline sets a new minimum qualifying rate, or stress test, for uninsured mortgages at the higher of the five-year benchmark rate published by the Bank of Canada, the central bank, or the contractual mortgage rate plus 2%. Lenders also will be required to impose and continuously update more effective loan-to-value (LTV) limits and measurements.

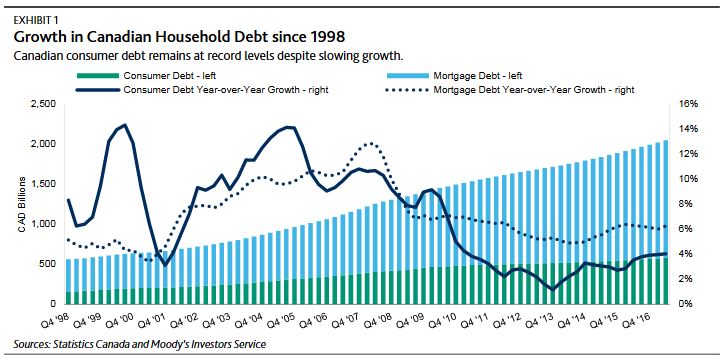

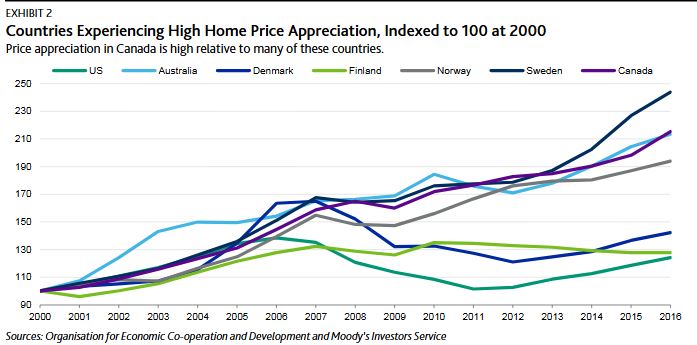

A key vulnerability of Canadian banks is the high and rising level of private-sector debt/GDP. Canadian mortgage debt outstanding has more than doubled in the past 10 years (see Exhibit 1) and the index of house prices to disposable income has increased 25% over this period (see Exhibit 2), raising the prospect that real estate overvaluation is driving up overall household debt and overextending borrowers.

OFSI’s action is the latest in a series of macro-prudential measures aimed at slowing house-price appreciation in Canada and moderating the availability of mortgage financing. These measures will address the increasing risk that that growing private-sector debt will weaken Canadian banks’ asset quality. Canada’s growing consumer debt and elevated housing prices threaten to make consumers and Canadian banks more vulnerable to downside risks.

In addition to requiring that all uninsured mortgages be stress-tested against a potential rise in interest rates (high-ratio insured mortgages are already required to meet such tests to qualify for mandatory mortgage insurance), the guideline requires that banks establish and adhere to risk-appropriate LTV limits that keep current with market trends. Additionally, the guideline expressly prohibits banks from arranging with another lender a mortgage, or a combination of a mortgage and other lending products (known as bundled mortgages), in any form that circumvents a bank’s maximum LTV ratio.

Housing prices are at record highs owing to price increases in the urban areas of Toronto, Ontario, and Vancouver, British Columbia. Macro-prudential initiatives dampened volumes and prices in Toronto over the summer, but the effects of similar moves in Vancouver last year appear to be lessening this year as prices regain momentum. We believe that high consumer leverage could result in future asset-quality deterioration in an economic downturn or a housing price correction. Although Canadian banks have demonstrated prudent underwriting standards in the past, this is attributable in part to thoughtful regulatory oversight.

The new guideline follows a consultation period that ended in August. Some industry participants recommended a delay in implementation, cautioning that the combined effect of multiple macro-prudential measures affecting the mortgage market risked unduly depressing the housing market, thereby triggering a severe price correction.