We turn our attention to VIC and Greater Melbourne with the latest mortgage stress mapping. Read about our approach here.

We are looking at owner occupied loans, with data to 1st March 2017.

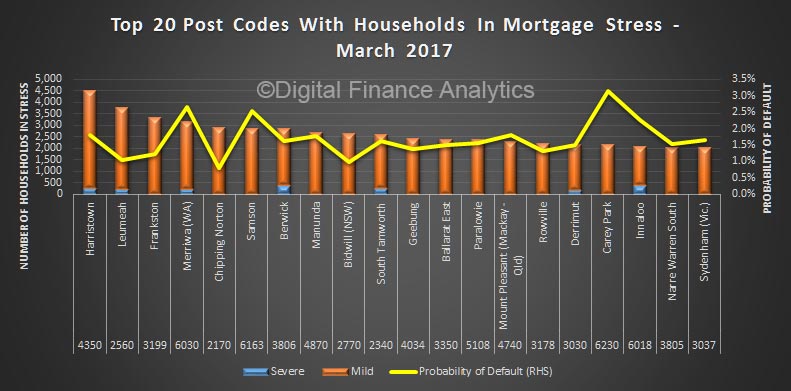

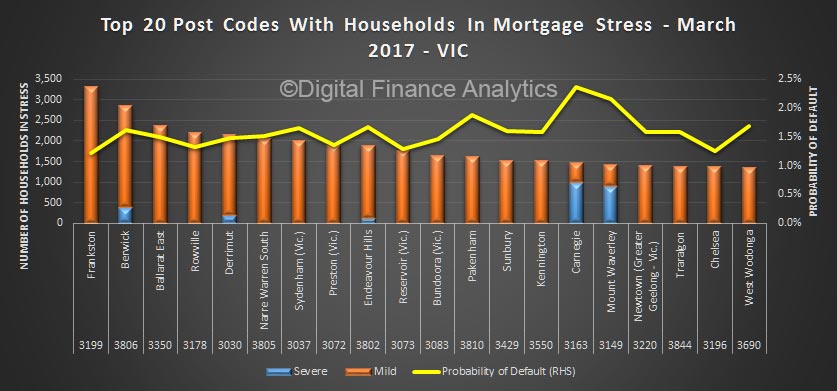

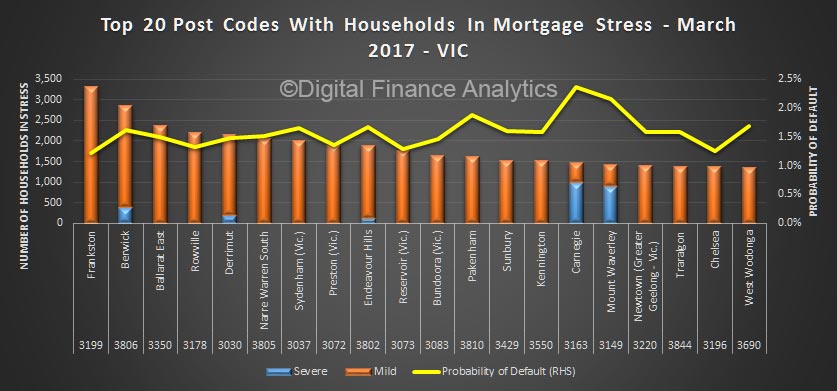

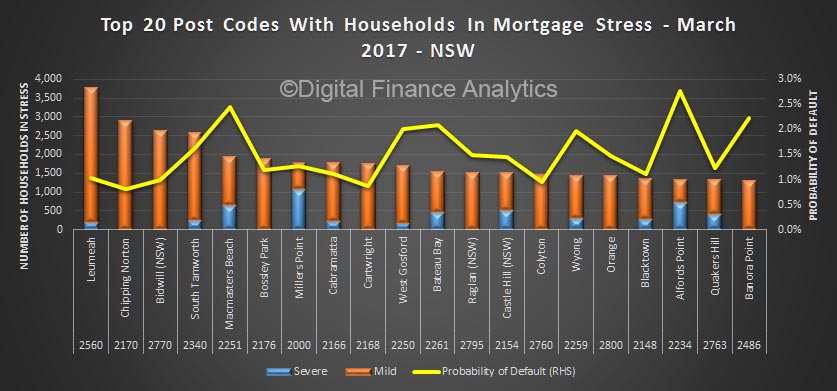

First here are the top twenty post codes across Victoria with the largest numbers of households in mortgage stress.

Frankston, 3199 heads the list and is suburb of Melbourne on the Mornington Peninsula about 39 kms from the CBD. More than 30% of households have a mortgage here, and the average age is 38 years old.

Frankston, 3199 heads the list and is suburb of Melbourne on the Mornington Peninsula about 39 kms from the CBD. More than 30% of households have a mortgage here, and the average age is 38 years old.

Next is Berwick, 3806, a suburb of Melbourne, South East and about 41 kms from the CBD. More than 52% of households have a mortgage and the average age is 35 years. Berwick has a relatively higher proportion of severely stressed households (shown by the blue bar above). These households are in more immediate danger of potential default.

Third is Ballarat East, 3350, a suburb of South Western Victoria, Ballaratt, and about 99 kms from Melbourne. More than 30% of households here have a mortgage and the average age is 38 years.

Fourth is Rowville, 3178, a suburb of Melbourne, South East and about 26 kms from Melbourne. The average age is 36 years and 54% of households have a mortgage.

Fifth is Derrimut, 3030, a suburb of Melbourne, Geelong, and 18 kms from the CBD. The average age is 29 years and more than 70% of households have a mortgage. Note again the number of severely stressed households in the district.

Finally, note Carnegie, 3163, a suburb of Melbourne, East and about 11 kms from the CBD. 28% of households have a mortgage, and the average age is 35 years, but there are more severely stressed households here, than stressed. We think this is an indication of potential relatively higher risks.

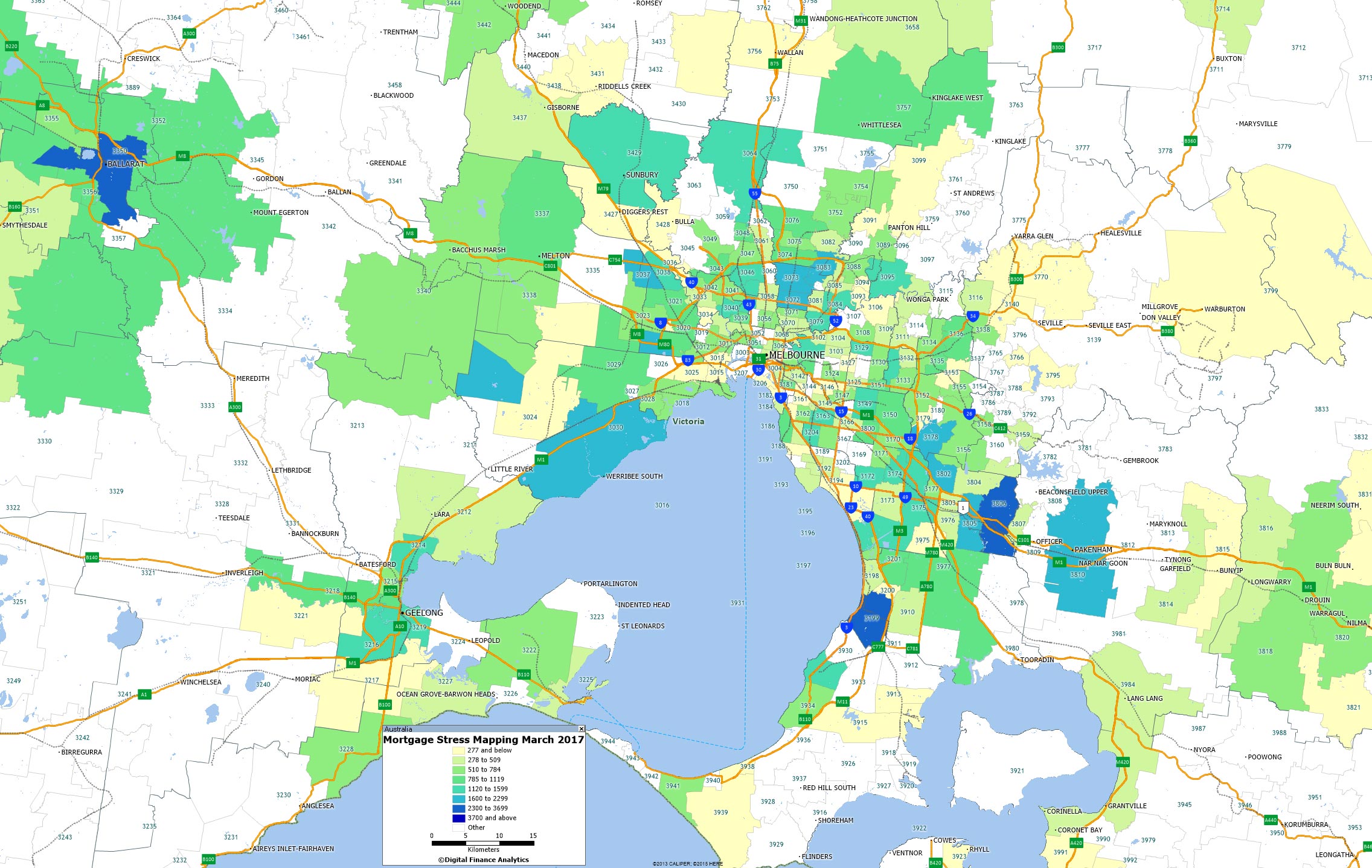

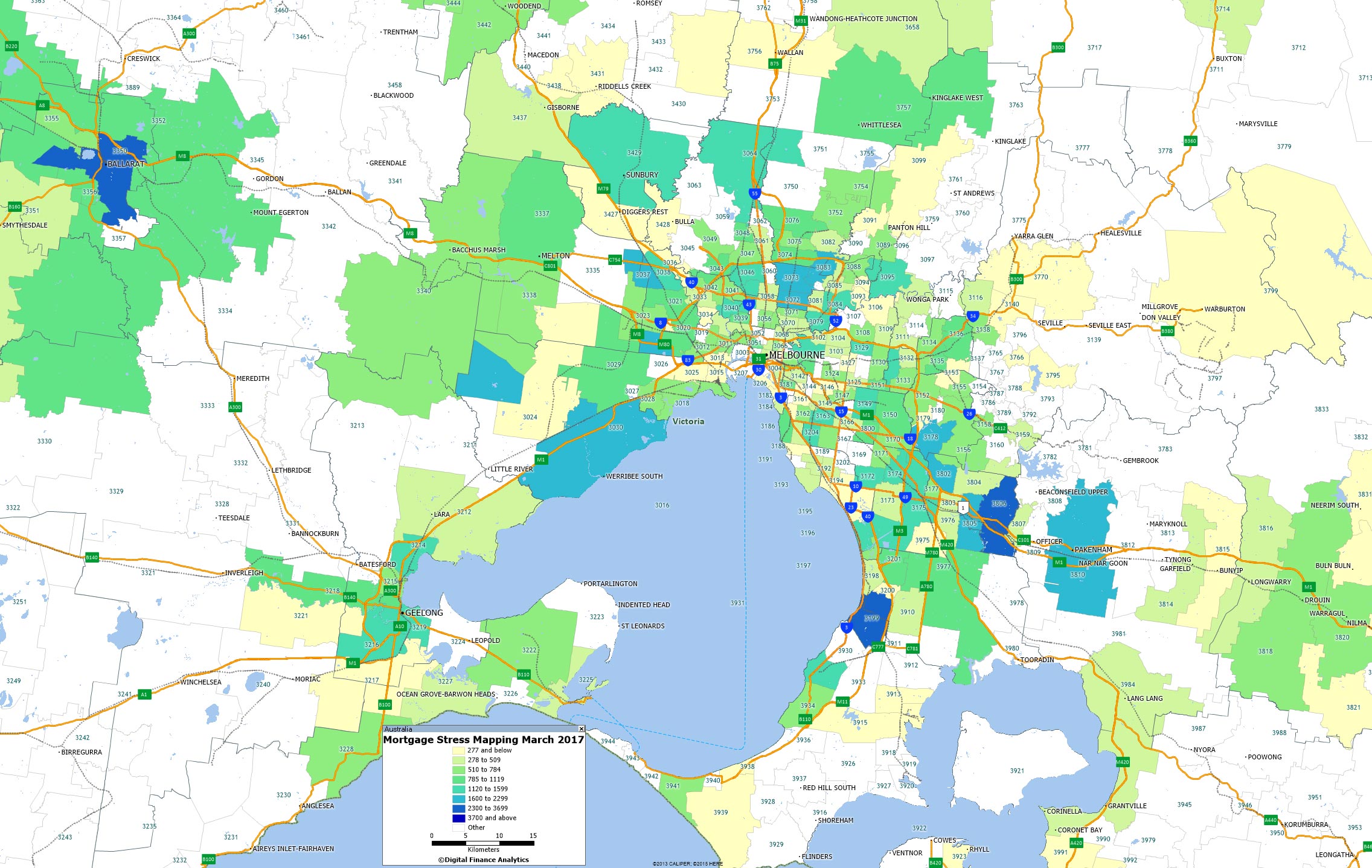

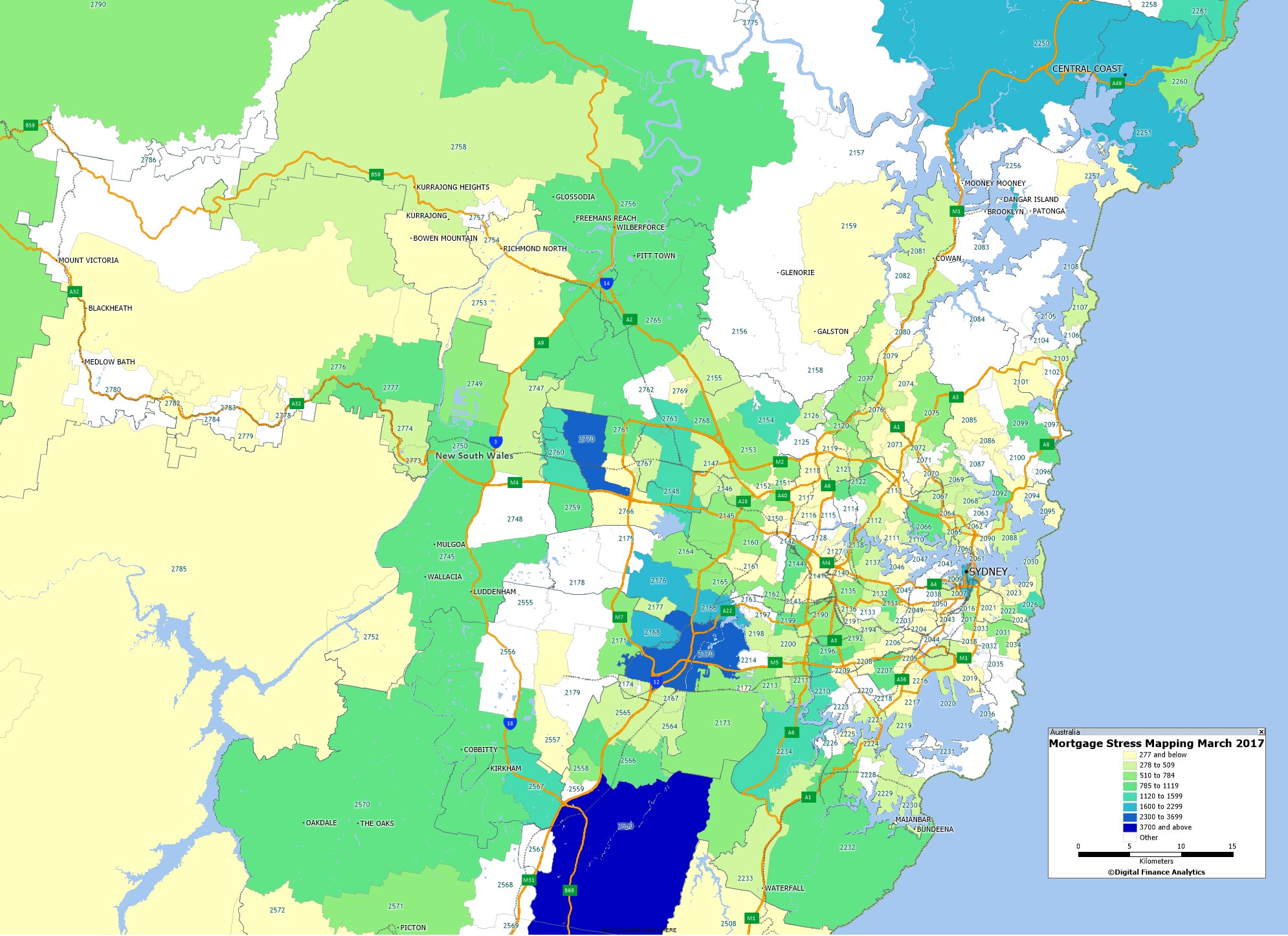

Here is a stress geo-map for the areas around Greater Melbourne. The Blue areas shows the highest stress counts.

Next time we will look at Greater Perth.

Next time we will look at Greater Perth.

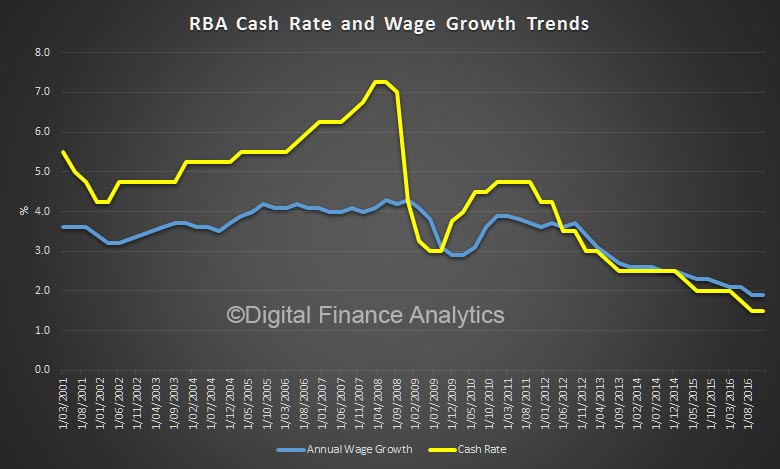

“If the cash rate goes to 6 per cent then you would expect to see a lot people in strife. Particularly with wage growth and inflation at such low levels so that does increase vulnerability to rises to interest rates” Mr Wilkins said.

“If the cash rate goes to 6 per cent then you would expect to see a lot people in strife. Particularly with wage growth and inflation at such low levels so that does increase vulnerability to rises to interest rates” Mr Wilkins said.