Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Adrian Orr spoke on “Higher capital better for banking system and NZ“.

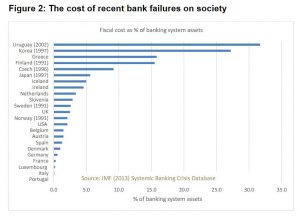

This is probably one of the most significant speeches on the issue, as it gets to the core thinking driving bank regulation. Essentially it is this. If there were to be a financial crisis, experience has shown the costs to the broader economy are substantial, and are born by society.

As a result, Orr argues that while a significant toolkit is available to lean against these risks, the cornerstone is lifting bank capital.

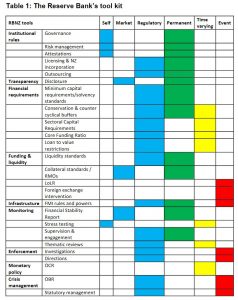

Note though that the toolkit includes under crisis management OBR – deposit bail-in!

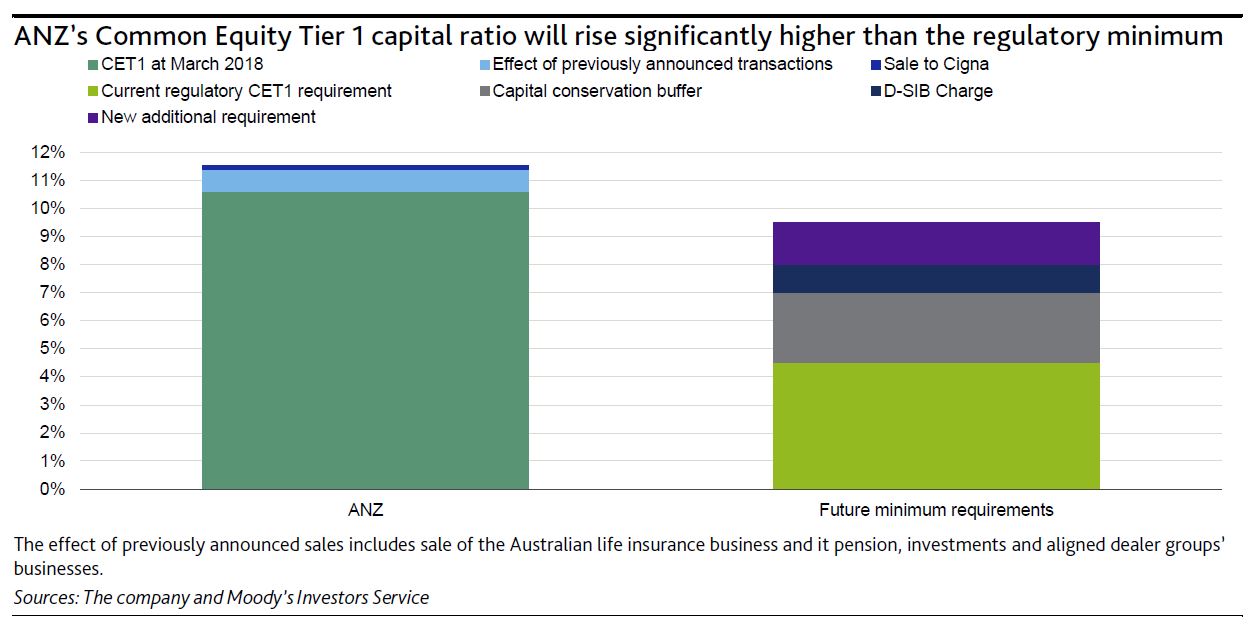

As a result, the amount of capital required will be significantly higher.

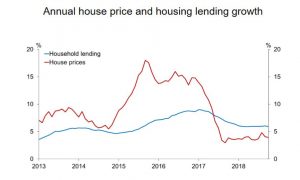

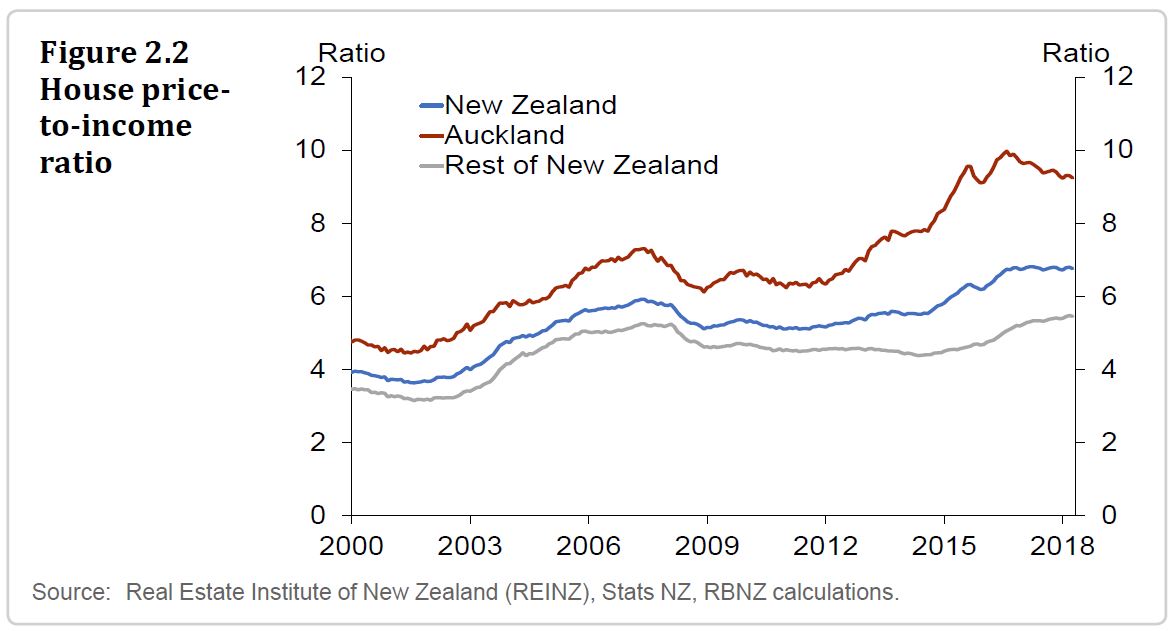

Implicitly, this approach enables the financial system to continue to expand, to drive debt higher (as we saw in his recent post), with the financial stability risks offset by higher capital. But as we have said many times, this faith in ever great debt as a growth lever is deeply flawed. And those borrowing will be required to pay more, as higher capital costs!

Here is the speech in full.

The Reserve Bank is tasked with ensuring the banking system is both sound and efficient. To achieve our task we have a range of tools (see Table 1). The most important tool in our kit is ensuring banks hold sufficient capital (equity) to be able to absorb unanticipated events. The level of capital reflects the bank owners’ commitment – or skin in the game – to ensure they can operate in all business conditions, bringing public confidence.

Given its importance, we have been undertaking a review of the optimal level of capital for the New Zealand system. We conclude that more capital is better. We are sharing our work with the banking sector and public, and expect to hear one side of the story loud and clear, that capital costs banks. We need to hear a broader perspective than that, to best reflect New Zealand’s risk appetite.

What have we done in practice?

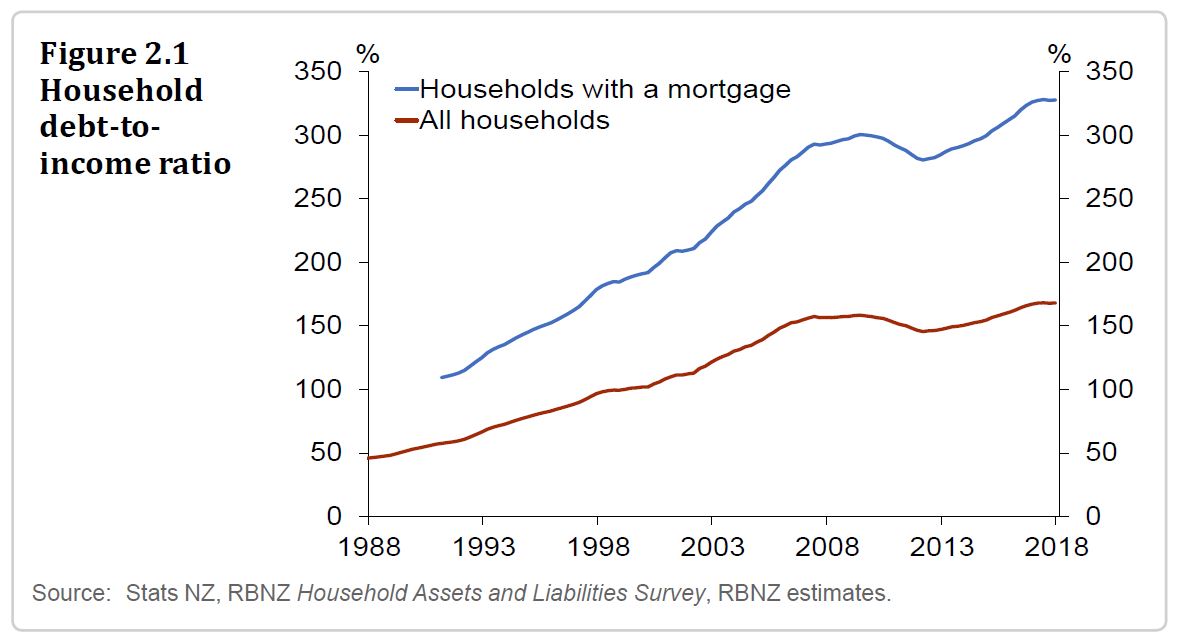

The Reserve Bank needs to ensure there is sufficient capital in the banking “system” to match the public’s “risk tolerance”. This is because it is the New Zealand public – both current and future citizens – who would bear the social brunt of a banking mess.

We know one thing for sure, the public’s risk tolerance will be less than bank owners’ risk tolerance. How do we know this? Surely the more capital a bank has the safer it is and the more it can lend. Why don’t banks hold as much capital as they can?

First, there is cost associated with holding capital, being what the capital could earn if it was invested elsewhere. Second, bank owners can earn a greater return on their investment by using less of their own money and borrowing more – leverage. And, the most a bank owner can lose is their capital. The wider public loses a lot more (see Figure 2).

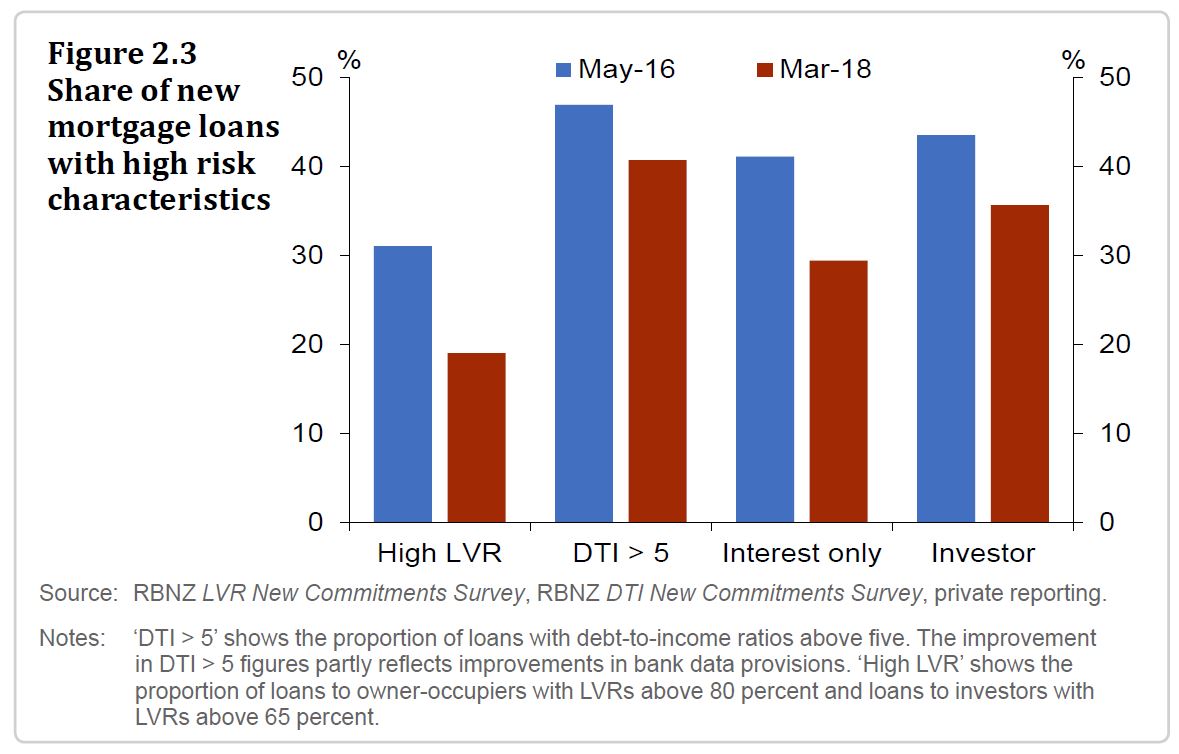

Hence, we need to impose capital standards on banks that matches the public’s risk tolerance. We have been reassessing the capital level in the banking sector that minimises the cost to society of a bank failure, while ensuring the banking system remains profitable.

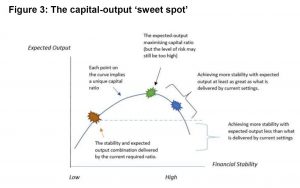

The stylised diagram in Figure 3 highlights where we have got to. Our assessment is that we can improve the soundness of the New Zealand banking system with additional capital with no trade-off to efficiency.

In making this assessment, our recent work makes the explicit assumption that New Zealand is not prepared to tolerate a system-wide banking crisis more than once every 200 years. We have calibrated our ‘sweet spot’ thinking about economic ‘output’ and financial stability benefits.

How did we arrive at this position?Current levels of capital are based on international standards, and are not optimal for any one country. The standards are also a minimum. There is a clear expectation that individual countries tailor the standards to their financial system’s needs.

Banks also hold more capital than their regulatory minimums, to achieve a credit rating to do business. The ratings agencies are fallible however, given they operate with as much ‘art’ as ‘science’.

Bank failures also happen more often and be more devastating than bank owners – and credit ratings agencies – tend to remember. The costs are spread across the public and through time.

Many large banks are foreign owned – especially in New Zealand. Their ‘parents’ are subject to capital requirements in their home and host country. This creates continuous tension as to who gets the lion’s share of capital and failure management support. It would be naïve to expect a foreign taxpayer to bail out a domestic banking crisis.

Hence, New Zealand needs to assess its own risk tolerance, and decide who pays to clean up any mess and the scale of that mess.

A word of caution. Output or GDP are glib proxies for economic wellbeing – the end goal of our economic policy purpose. When confronted with widespread unemployment, falling wages, collapsing house prices, and many other manifestations of a banking crisis, wellbeing is threatened. Much recent literature suggests a loss of confidence is one cause of societal ills such as poor mental and physical health, and a loss of social cohesion. If we believe we can tolerate bank system failures more frequently than once-every-200 years, then this must be an explicit decision made with full understanding of the consequences.