The OECD has released a report Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class which underscores the fact that relative to the more affluent, those in the middle are getting squeezed. 40% are financially at risk. Timely given the current Australian election!

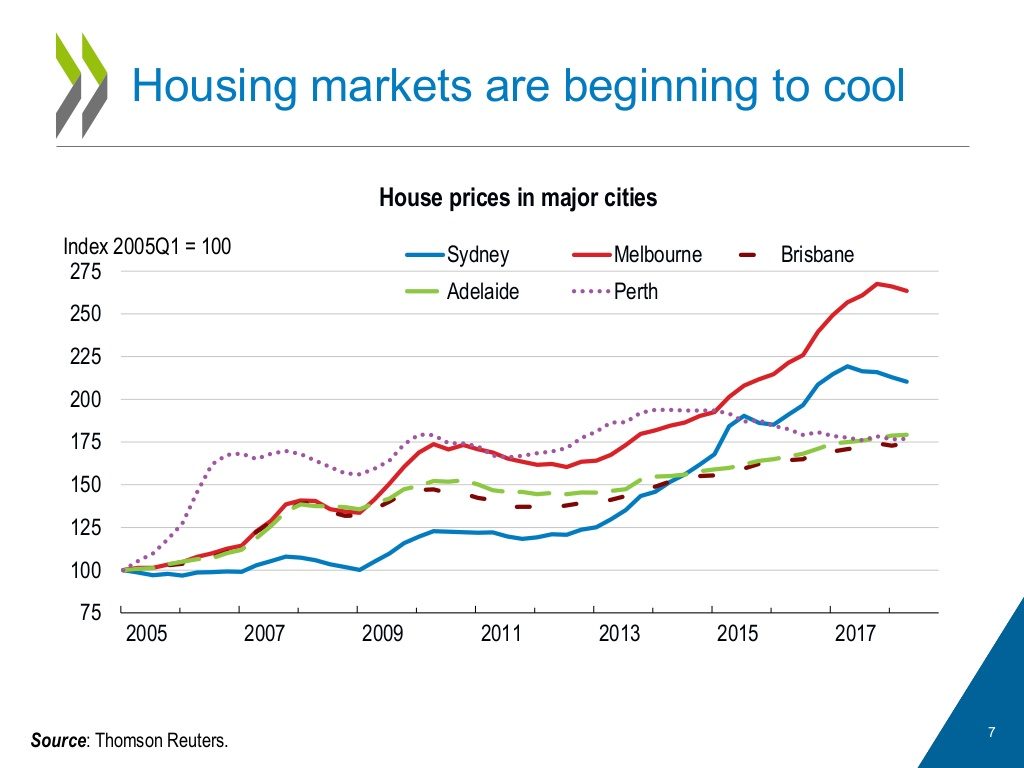

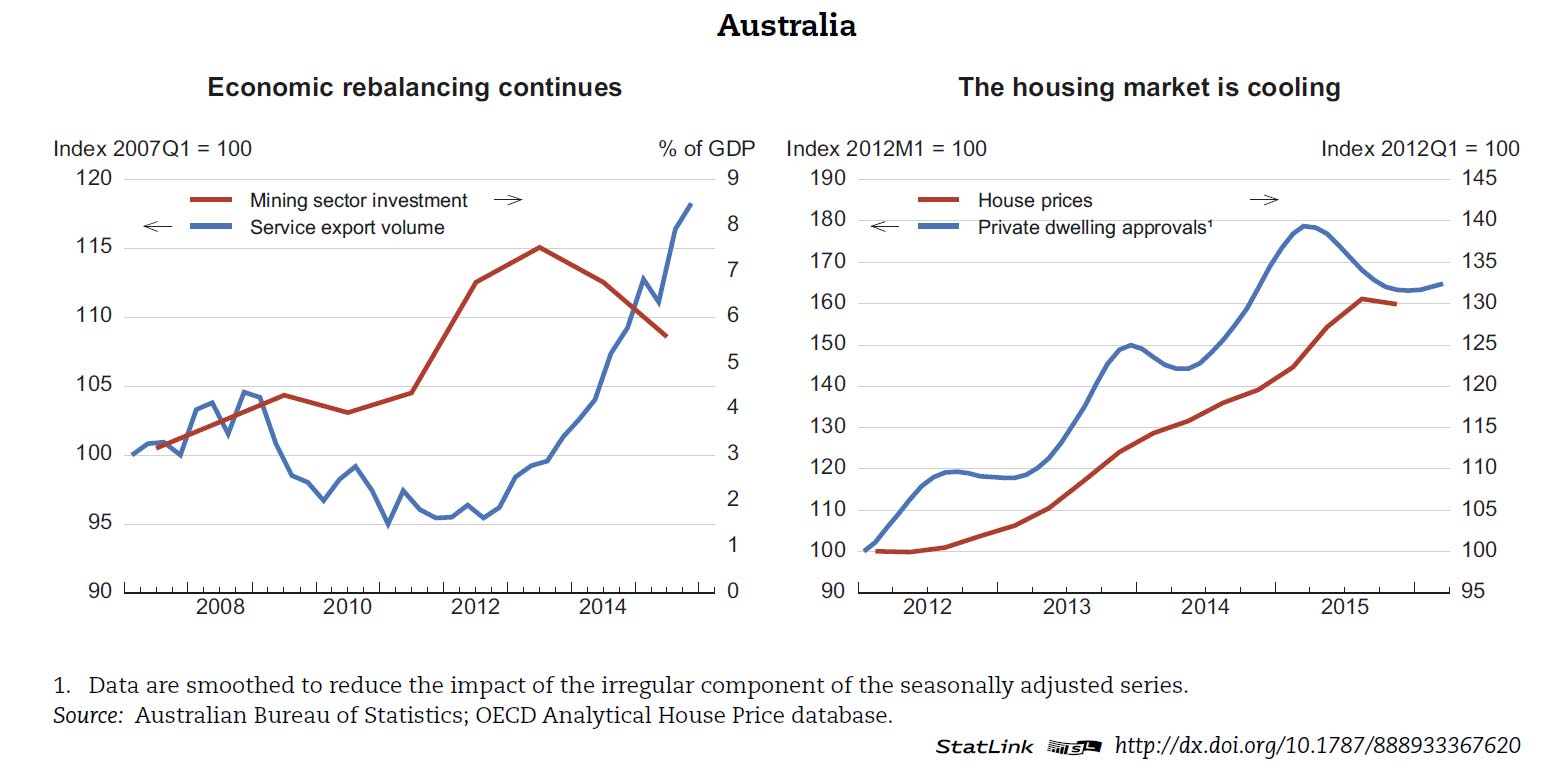

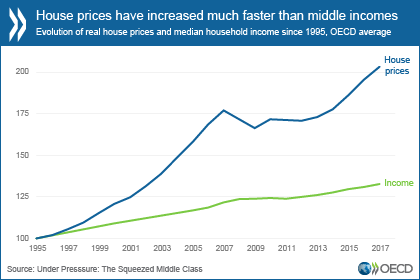

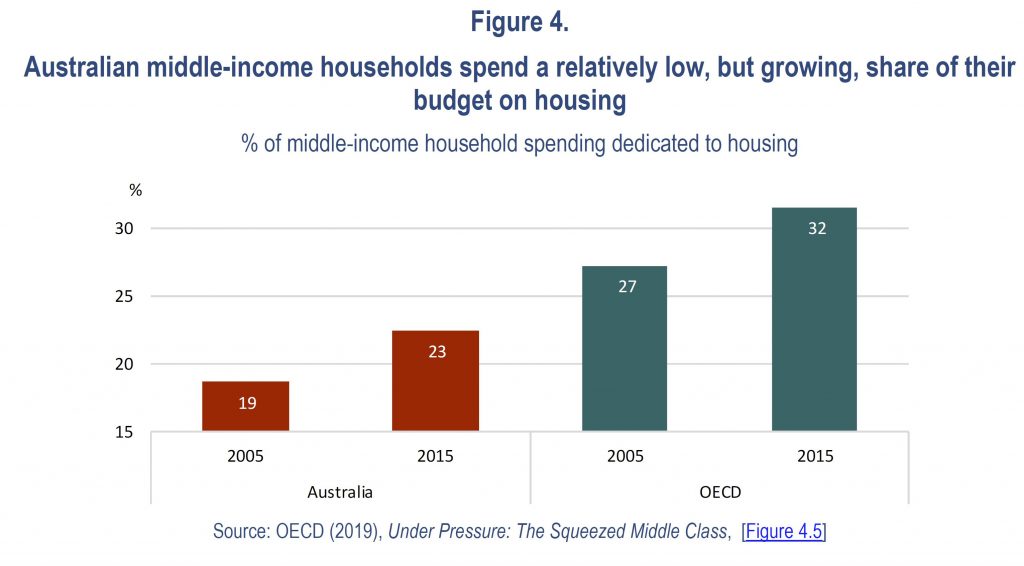

Much of this is because of the high costs of housing relative to incomes.

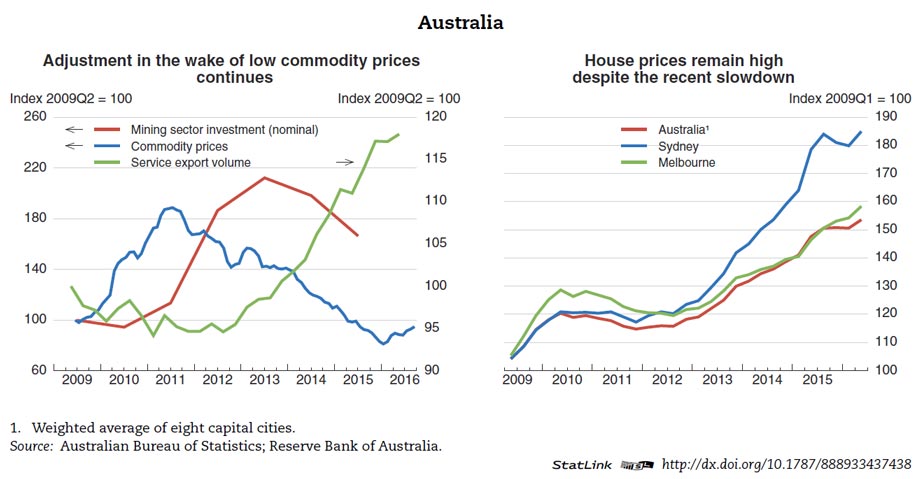

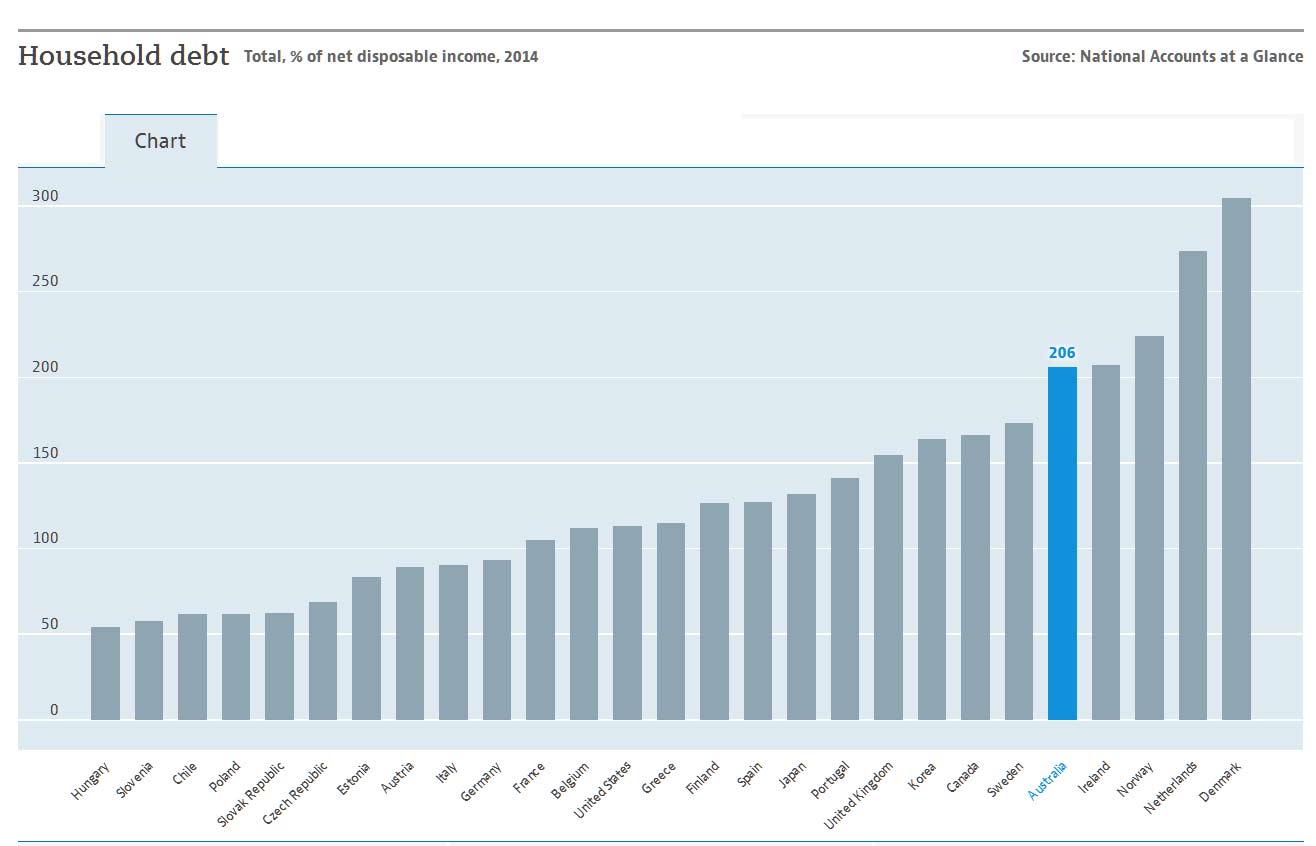

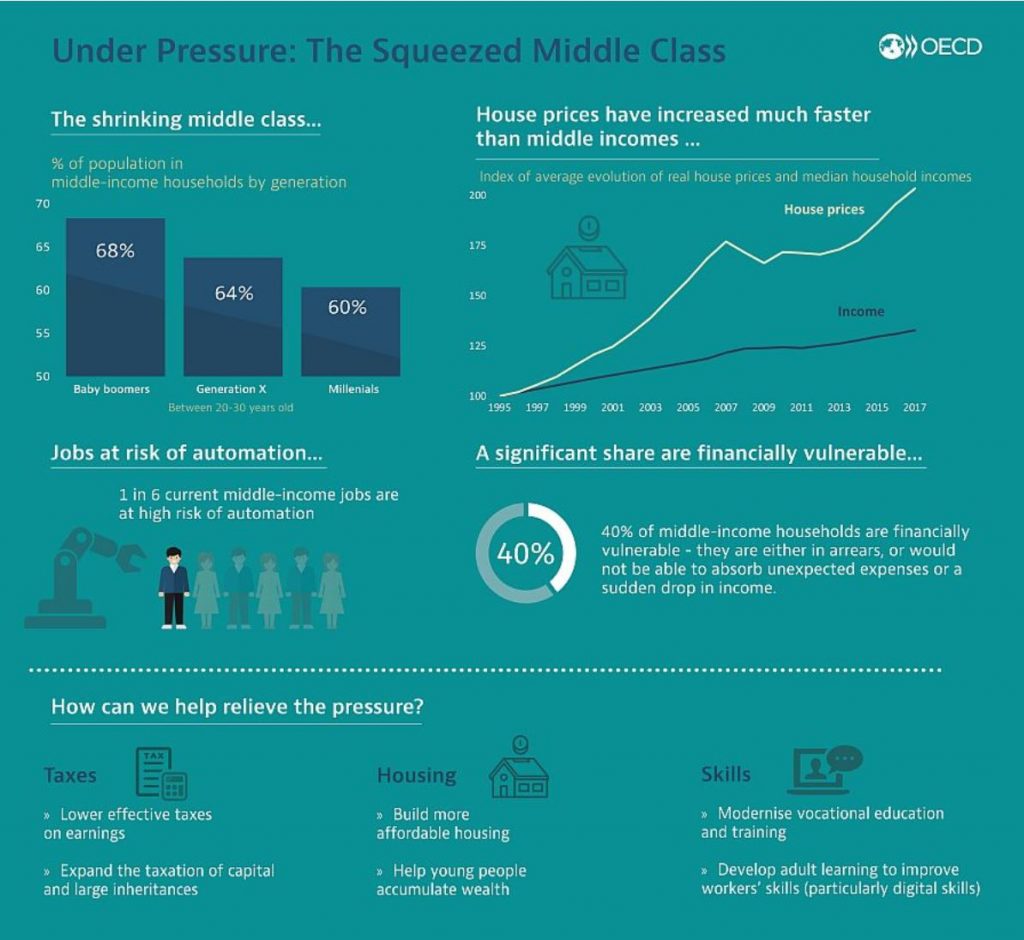

The cost of a middle class lifestyle has increased faster than inflation. Housing, for example, makes up the largest single spending item for middle-income households, at around one third of disposable income, up from a quarter in the 1990s. House prices have been growing three times faster than household median income over the last two decades

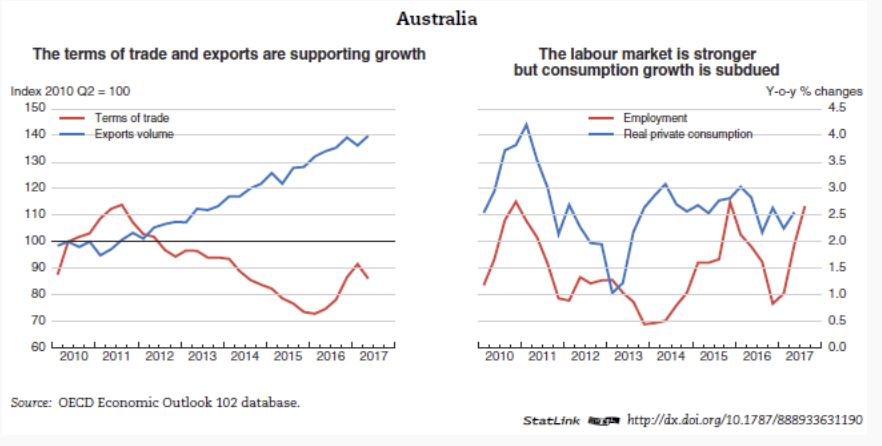

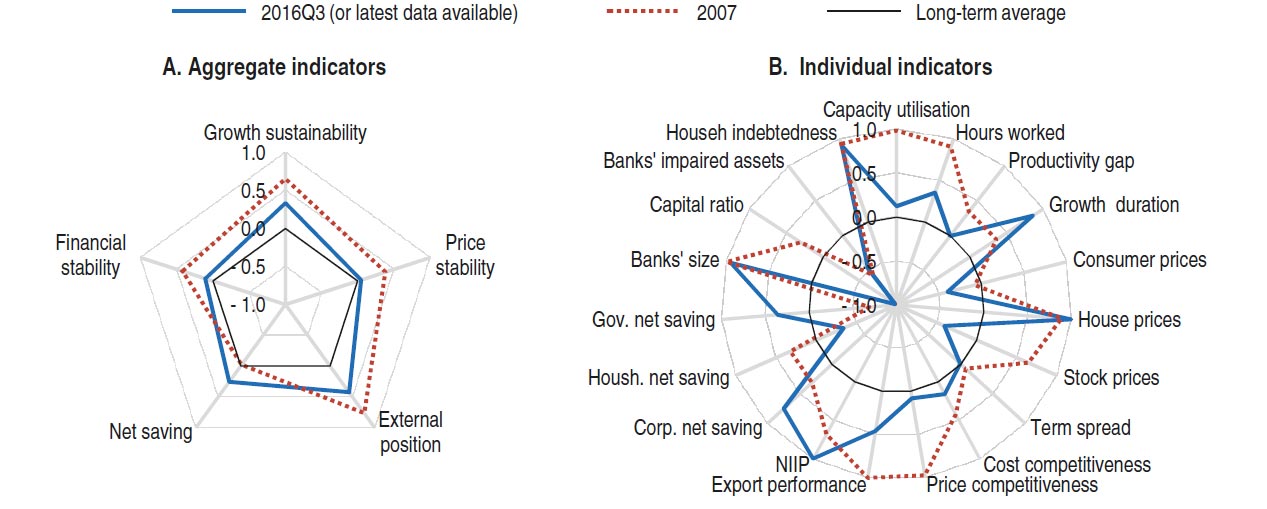

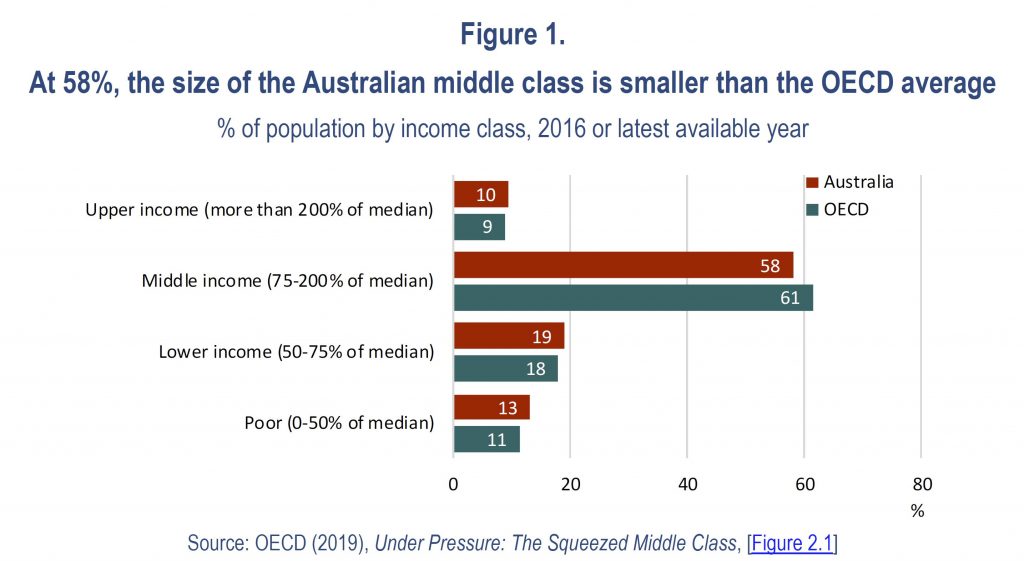

The report includes Australian specific data. At 58%, the size of the Australian middle class is smaller than the OECD average.

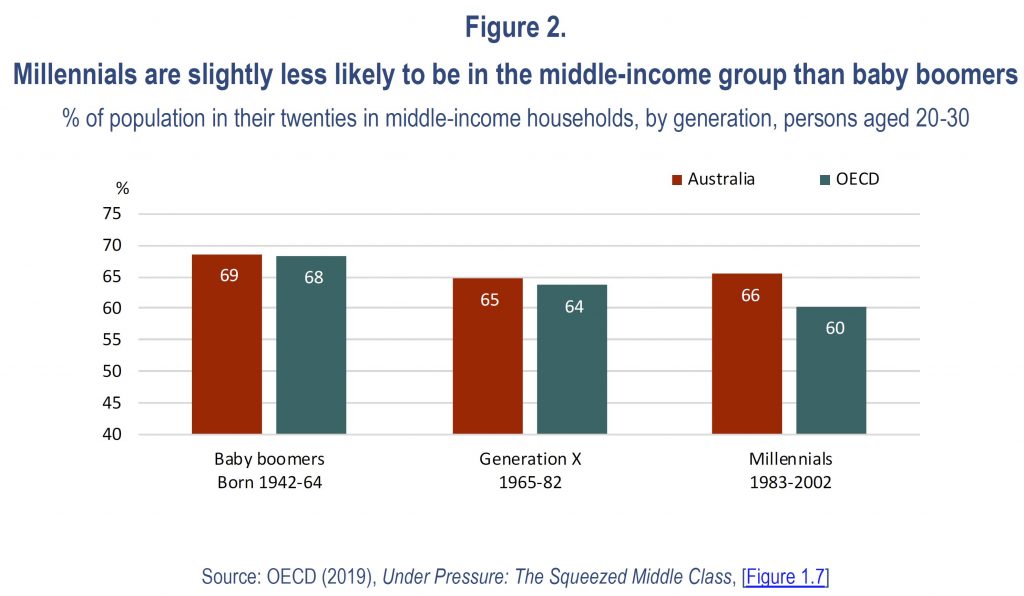

Millennials are slightly less likely to be in the middle-income group than baby boomers.

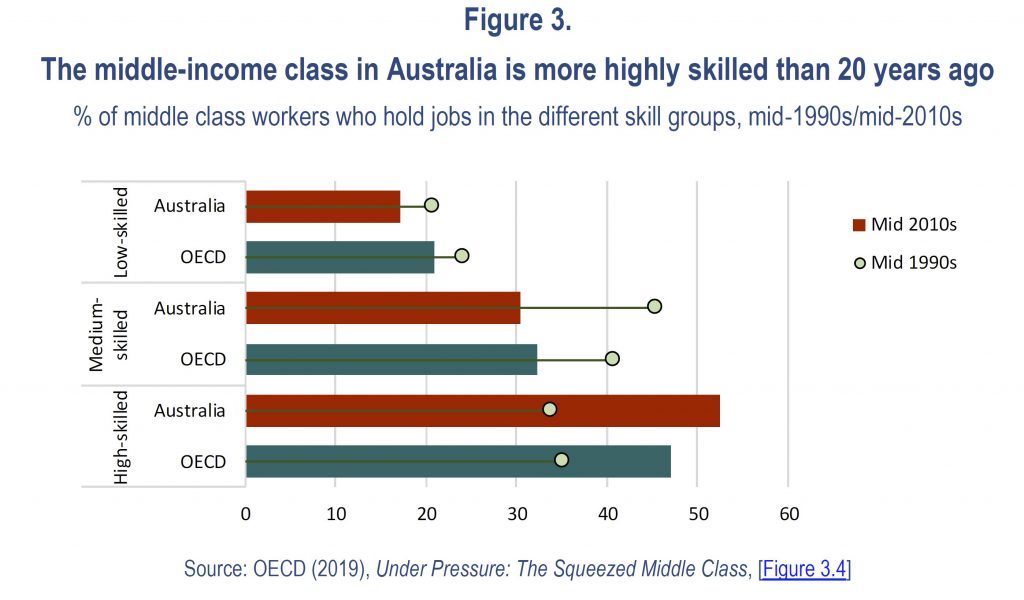

The middle-income class in Australia is more highly skilled than 20 years ago

Australian middle-income households spend a relatively low, but growing, share of their budget on housing.

More generally, the report says that the middle class has shrunk in most OECD countries as it has become more difficult for younger generations to make it to the middle class, defined as earning between 75% and 200% of the median national income. While almost 70% of baby boomers were part of middle-income households in their twenties, only 60% of millennials are today

The economic influence of the middle class has also dropped sharply. Across the OECD area, except for a few countries, middle incomes are barely higher today than they were ten years ago, increasing by just 0.3% per year, a third less than the average income of the richest 10%

“Today the middle class looks increasingly like a boat in rocky waters,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría, launching the report in New York with Luis Felipe Lopéz-Calva, Assistant Secretary General, Latin America and the Caribbean, United Nations Development Programme. “Governments must listen to people’s concerns and protect and promote middle class living standards. This will help drive inclusive and sustainable growth and create a more cohesive and stable social fabric.

Gabriela Ramos, OECD Chief of Staff and Sherpa overseeing the Organisation’s work on Inclusive Growth, presented in more details the main findings of the report, saying “our analysis delivers a bleak picture and a call for action. The middle class is at the core of a cohesive, thriving society. We need to address their concerns regarding living costs, fairness and uncertainty.”

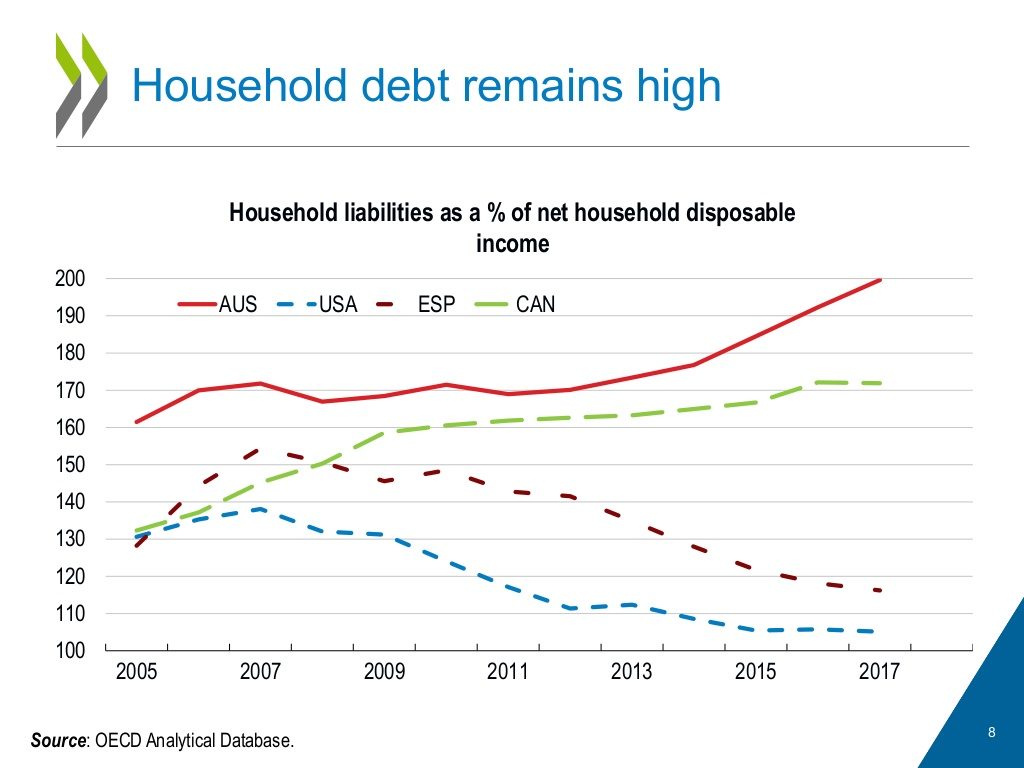

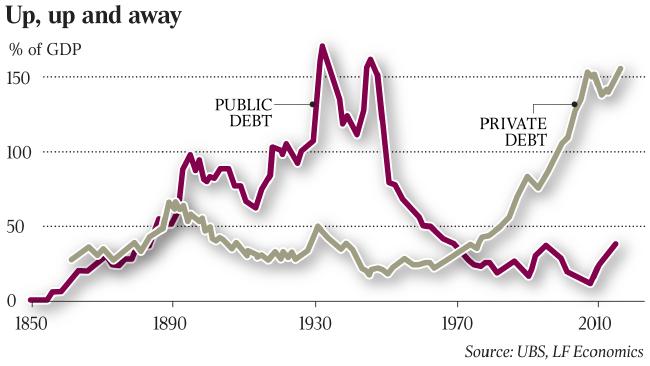

More than one in five middle-income households spend more than they earn and over-indebtedness is higher for them than for both low-income and high-income households. In addition, labour market prospects have become increasingly uncertain: one in six middle-income workers are in jobs that are at high risk of automation, compared to one in five low-income and one in ten high-income workers

To help the middle class, a comprehensive action plan is needed, according to the OECD. Governments should improve access to high-quality public services and ensure better social protection coverage. To tackle cost of living issues, policies should encourage the supply of affordable housing. Targeted grants, financial support for loans and tax relief for home buyers would help lower middle-income households. In countries with acute levels of housing-related debt, mortgage relief would help overburdened households get back on track

As temporary or unstable jobs – often offering lower wages and job security – increasingly replace traditional middle-class jobs, more investment is needed in vocational education and training systems. Social insurance and collective bargaining coverage for non-standard workers, such as part-time or temporary employees or self-employed, should be extended

Finally, to foster fairness of the socio-economic system, policies need to consider shifting the tax burden from labour income to income from capital and capital gains, property and inheritance, as well as making income taxes more progressive and fair.