The RBA minutes for October are decidedly bearish, clearly the battery in their rose-tinted specs as run down, revealing the mounting risks in the economy. Probably more risks ahead, more cuts and the proverbial QE in some form…

International Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of global economic conditions by noting that heightened policy uncertainty was affecting international trade and business investment. This had continued to be apparent in a range of indicators, including new export orders and investment intentions. Conditions in the manufacturing sector had remained subdued, partly because of ongoing US–China trade tensions. These tensions had led to a contraction in bilateral trade between the United States and China, which was resulting in the diversion of some activity to other economies. Members noted that the trade and technology disputes continued to pose significant downside risks to the global economic outlook.

In general, conditions in the services sector had been relatively resilient in most advanced economies, supported by strong labour market conditions. Employment growth had continued to outpace growth in working-age populations, unemployment rates had remained at low levels and wages growth had risen. Nevertheless, inflation had remained low, although core inflation had picked up in the United States in recent months.

In the United States, GDP growth appeared to have slowed a little further in the September quarter. Growth in core capital goods orders and investment intentions had declined, whereas growth in consumption had remained robust. In the euro area, the weakness in output growth in the June quarter had been broadly based. Industrial production had fallen, particularly in Germany, and investment intentions had remained below average. In Japan, exports had declined further, although output growth in the September quarter had been supported by above-average household spending ahead of an increase in the consumption tax in October.

In east Asia, export volumes had been flat for several months. Other indicators of activity, such as industrial production and surveys of manufacturing conditions, had shown tentative signs of stabilising. Growth in output had also slowed in India, driven by weakness in consumption. Members noted that the political unrest in Hong Kong had affected economic activity there to a significant extent.

In China, a range of indicators suggested that the pace of economic activity had slowed since the start of the year. Economic indicators remained subdued in August, although they had recovered a little from broad-based weakness in July. Growth in industrial production and retail sales had edged higher in August, and fixed asset investment growth had been broadly unchanged. Conditions in housing markets also appeared to have softened. In response to the slowing in activity, the authorities had announced further measures to ease policy in September. Chinese demand for imported iron ore and coal had increased, supported by ongoing investment in infrastructure.

The iron ore benchmark price had continued to be volatile since the previous meeting. Members noted that supply concerns in the iron ore market had eased somewhat, and ongoing strength in Chinese steel demand had been met by an increase in iron ore imports. Oil prices had also been volatile, with the attacks on oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia having disrupted oil supply and exacerbated uncertainty in the region.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members noted that the main domestic economic news over the previous month had been the release of the national accounts data for the June quarter and updates on the labour and housing markets. On balance, the data had pointed to a continuation of recent trends.

The national accounts reported that the Australian economy had grown by 0.5 per cent in the June quarter. Year-ended growth had slowed to 1.4 per cent, the lowest outcome in a decade. Nevertheless, there had been a pick-up in quarterly GDP growth over the first half of 2019 compared with the second half of 2018. The pick-up had been driven by stronger growth in exports, led by exports of resources and manufacturing goods. Members noted that export demand was being supported by the lower level of the Australian dollar. Public demand had also been growing strongly, partly because of spending on the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Members observed that the drought had continued to affect the rural sector to a significant extent and that, as a result, farm output was expected to remain weak over the following year.

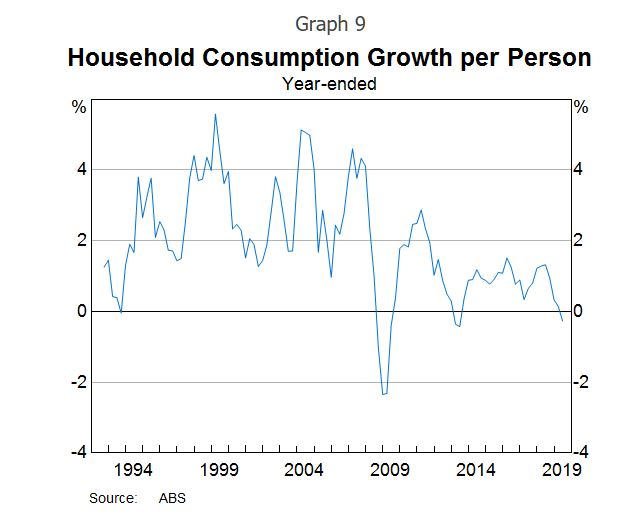

Growth in household disposable income had been subdued. Strong growth in income tax paid by households had been a contributing factor, as had been low growth in non-labour income, partly reflecting the effects of the drought on the farm sector. By contrast, strong employment growth had boosted growth in labour income.

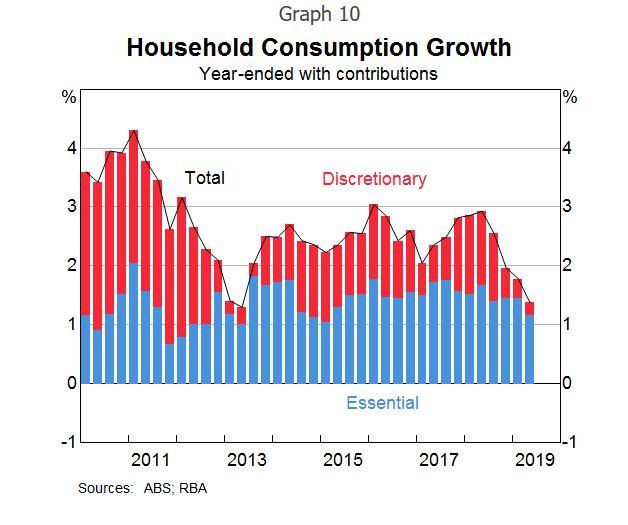

Consistent with the ongoing low growth in household disposable income, household consumption had increased by only 1.4 per cent over the year to the end of June. Members noted that there had not yet been evidence of a pick-up in household spending following the recent reductions in the cash rate and receipt of the tax offset payments, although they acknowledged that it may be too early to expect any signs of a pick-up. Retail sales had remained subdued in July and car sales had decreased in August. Despite weak reported retail sales conditions generally, on a slightly more positive note some contacts in the Bank’s liaison program had reported a mild pick-up in retail sales since July. Responses to consumer surveys in September had suggested that, on average, households planned to spend around half of their lump-sum tax payments, broadly in line with what had been assumed in the Bank’s most recent forecasts.

The residential construction sector had contracted further and this was expected to continue for some time. The decline in dwelling investment in the June quarter was greater than had been expected a few months earlier. Higher-density approvals had declined in July, to be at their lowest level in seven years; detached approvals had also declined in July. The Bank’s liaison program had continued to report weak pre-sales for higher-density developments. Taken together, this information implied that dwelling investment would decline further over coming quarters.

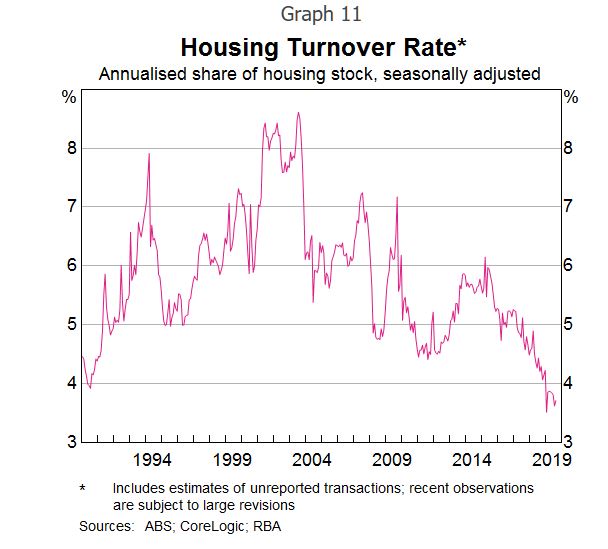

The turnaround in the established housing market had continued in September. Housing prices had increased further in Sydney and Melbourne, and auction clearance rates had remained high in both cities. The pace of growth in housing prices had also picked up in some other capital cities in recent months. However, housing turnover had remained low.

Business investment had decreased a little in the June quarter, driven by a decline in non-residential construction outside the mining sector. Nevertheless, the outlook for non-mining business investment remained favourable, supported by investment in infrastructure. Mining investment had picked up largely as expected. Members noted that mining investment was expected to continue to increase gradually, supported by projects both to sustain and to expand production. Survey measures of business conditions had remained around average in August; members noted that conditions in retailing were reported to have been very weak, while conditions in the mining industry had remained well above average.

Conditions in the labour market had continued to be mixed. Employment growth in August had remained stronger than growth in the working-age population, and the employment-to-population ratio had reached its highest level since late 2008. Employment had increased by 2½ per cent over the preceding year, the third successive year of strong employment growth. The participation rate had also increased to another record high. Members noted that the strong demand for labour had been met by an equally strong increase in supply. The unemployment rate had been around 5¼ per cent since April and the underemployment rate had remained above its recent low point. Looking ahead, job vacancies and advertisements had declined, suggesting that employment growth would probably moderate over the subsequent few quarters. Members noted that the ongoing subdued growth in wages implied that there continued to be spare capacity in the labour market.

Financial Markets

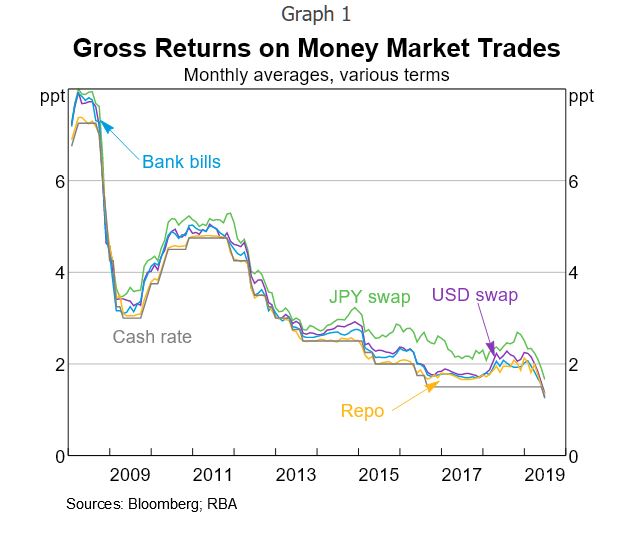

Members noted that financial conditions remained accommodative internationally and in Australia. Several major central banks had eased policy in September and market pricing implied that market participants expected the global economic expansion to be sustained by an extended period of policy stimulus. Expectations of further monetary easing had been partially scaled back in response to tentative signs of progress in the trade and technology negotiations between the United States and China and some better-than-expected US economic data. These developments had also supported the prices of equities and corporate bonds.

As expected, the US Federal Reserve had reduced its policy rate again by 25 basis points in September. The Federal Reserve had noted that, although the US economy had remained strong, easier policy was warranted given muted domestic inflation pressures, a weakening in global activity and persistent downside risks. Members of the Federal Open Market Committee did not anticipate a prolonged easing cycle, but continued to signal that they were willing to ease policy further if needed to sustain growth and meet the Federal Reserve’s inflation objective. Market pricing suggested that the federal funds rate was expected to decline by a further 50 basis points or so by mid 2020, which was a little less than had previously been anticipated.

The European Central Bank (ECB) had delivered a package of stimulus measures in response to inflation being persistently below the ECB’s target, protracted weakness in economic growth and continued downside risks. The package included cutting the ECB’s policy rate by 10 basis points to –0.5 per cent, exempting a portion of banks’ excess reserves from negative deposit rates, committing to not lifting rates until inflation returned sustainably to target, renewing purchases of government and private sector securities, and easing the conditions of the targeted long-term refinancing operations designed to encourage banks to lend to the private sector.

The People’s Bank of China had provided additional but targeted monetary stimulus, further cutting its reserve requirements, with larger adjustments for some smaller banks that are important providers of finance to small businesses. Chinese banks had also lowered the benchmark lending rate for corporate borrowers slightly.

Government bond yields in major markets had risen a little, with yields in Australia following suit. Nonetheless, bond yields remained very low, with a large portion of bonds in Europe and Japan trading at negative yields. Members noted that a sizeable proportion of the investors holding these negative-yielding bonds were constrained by their mandates or regulatory requirements, including asset managers, banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

Members noted that financing conditions for corporations remained favourable globally. Equity prices had remained close to recent peaks, spreads on corporate bonds were low and issuance volumes had been strong. In Australia, the cost of capital for corporations had been quite stable for some years, although more recently it had declined a little. Members also discussed hurdle rates for business investment, which had not changed much over recent times.

Major exchange rates had generally been little changed over September, with the US dollar having appreciated over the preceding two years or so on a trade-weighted basis. The Chinese renminbi had stabilised after its earlier depreciation, while the Japanese yen had depreciated, consistent with some easing of concerns about global risks. The Australian dollar had been little changed and remained around its lowest level in recent years.

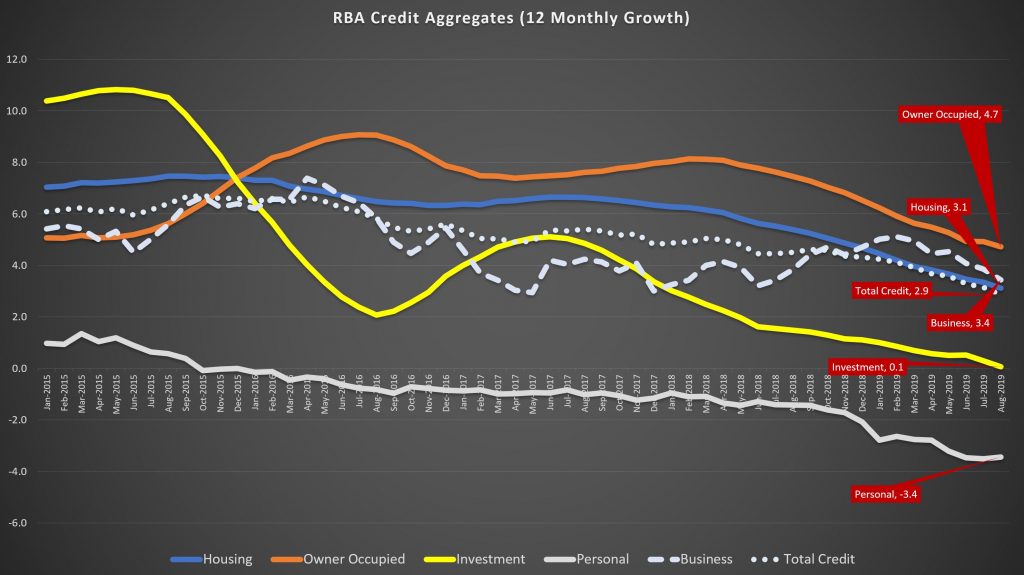

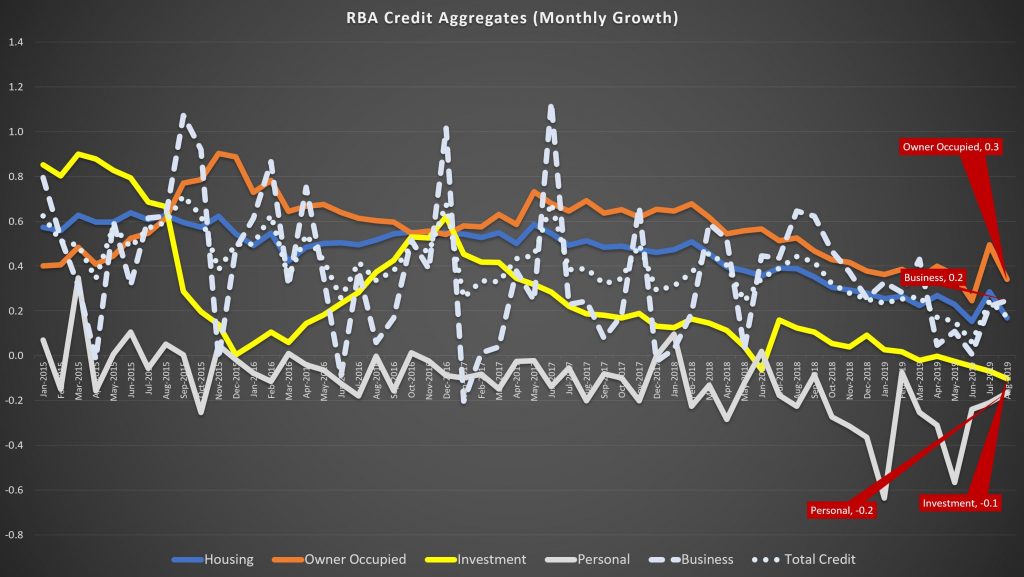

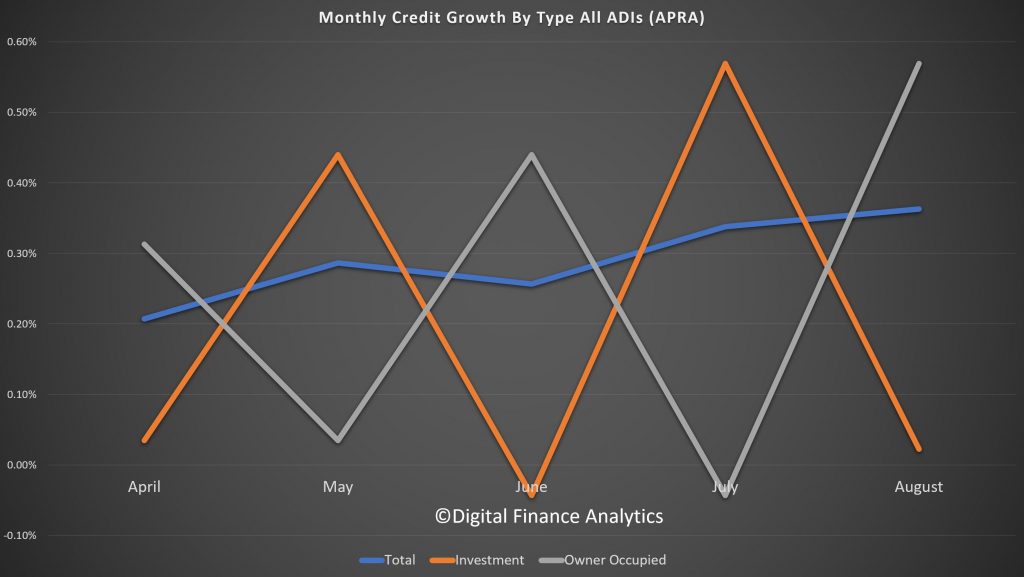

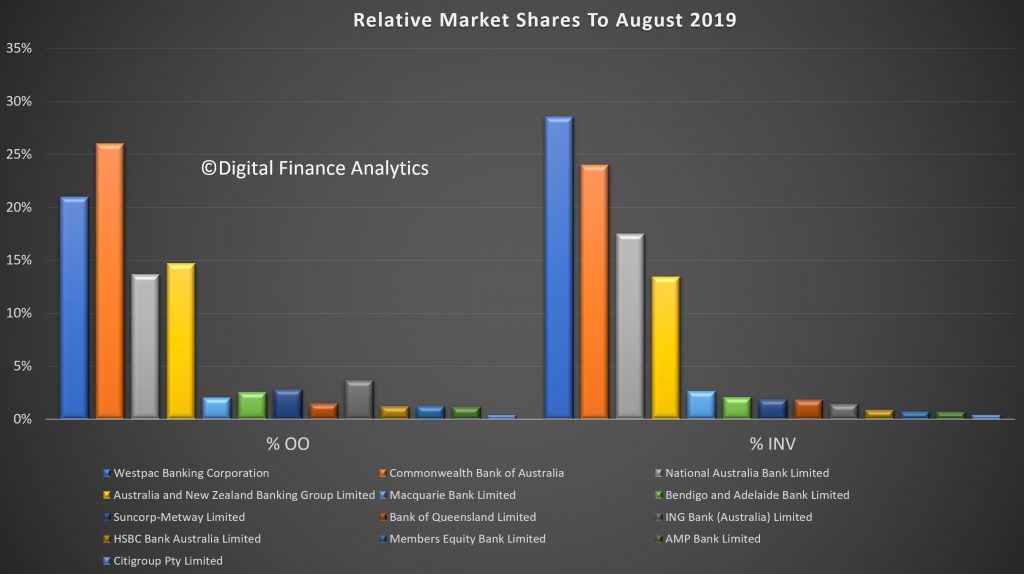

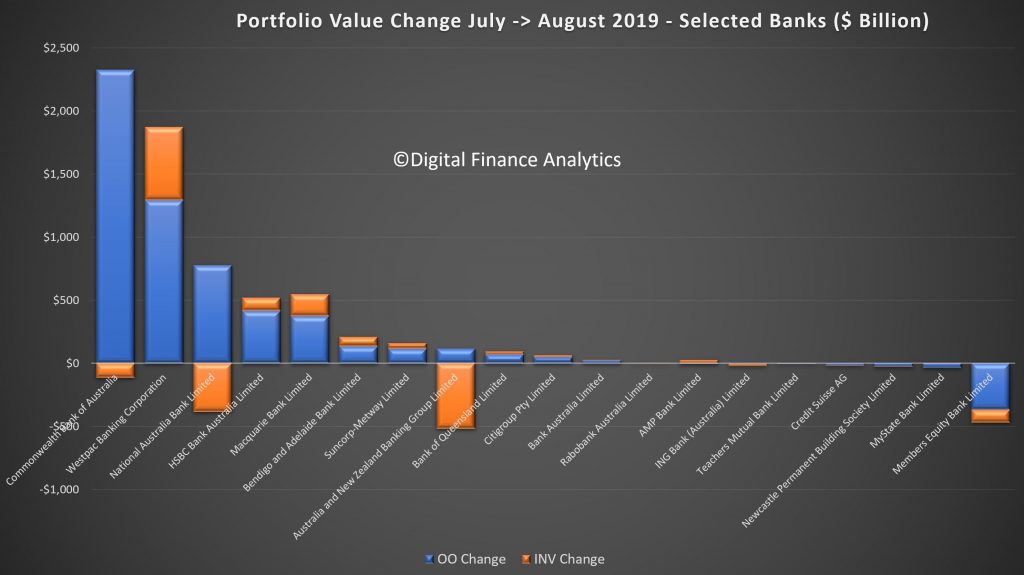

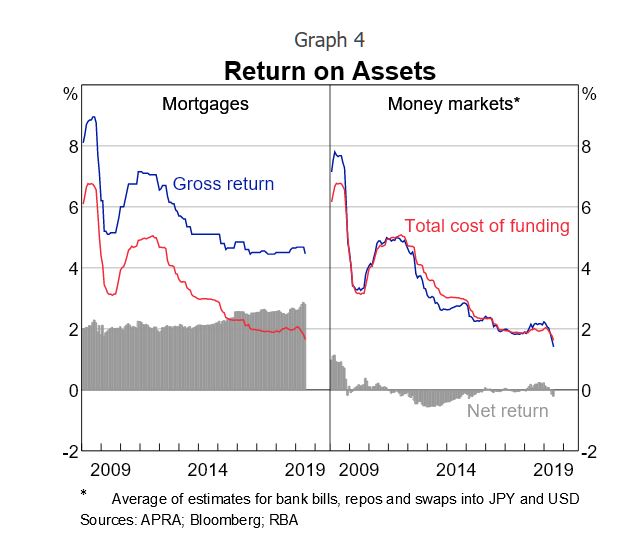

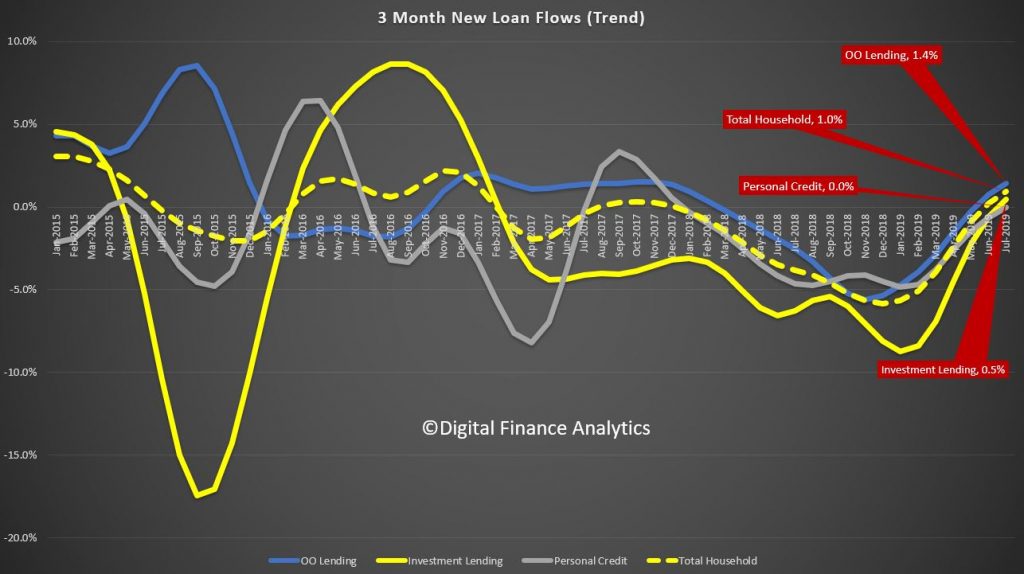

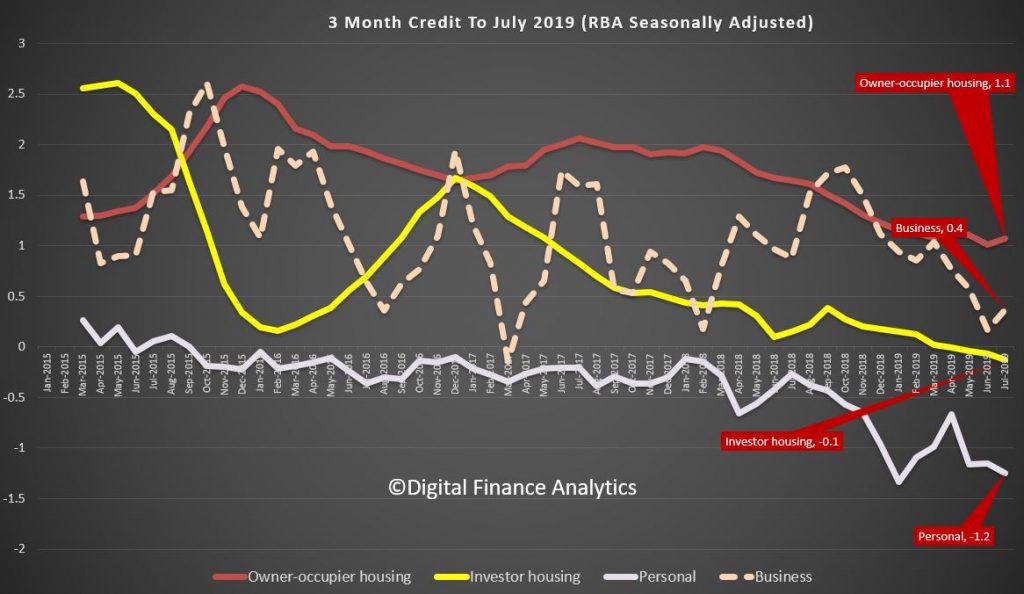

In Australia, borrowing rates for households and businesses, as well as banks’ funding costs, were at historically low levels. Housing loan approvals to both owner-occupiers and investors had increased in the three months to August, consistent with stronger conditions in some established housing markets. However, members noted that this increase in approvals had not yet translated into faster growth in housing credit. The pace of growth in housing credit for owner-occupiers had been fairly steady since the beginning of the year and the stock of housing credit for investors had continued to decline a little.

Financial market pricing indicated that a 25 basis points reduction in the cash rate was largely priced in for the October meeting, with a further reduction expected by mid 2020.

Financial Stability

Members were briefed on the Bank’s regular half-yearly assessment of the financial system.

Globally, investors were accepting low rates of compensation for bearing risk, despite the increased chance of significantly weaker economic growth. Members noted that a sharp slowdown in global growth could result from an escalation of the US–China trade and technology disputes or geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, Hong Kong or the Korean peninsula. Central banks had eased monetary policy in response to the potential for weaker growth, and additional easing was expected by markets, leading to falls in long-term government bond yields. Despite the increased uncertainty, risk premiums were low and in some cases had fallen further. The lower risk-free interest rates and low term, credit and liquidity risk premiums had seen many asset prices increase further. Any shock that caused markets to increase risk premiums or revise upwards expectations of future policy rates, such as a pick-up in inflation without accompanying stronger growth, could see a broad range of asset prices fall. Given debt levels were high in some non-financial sectors in some economies, a fall in asset prices could result in financial stress for some businesses and households, which could spill over to financial institutions.

Members observed that there had been strong growth in corporate debt in the United States, France and Canada, particularly lower-quality debt. Members noted that borrowers whose credit ratings fell below investment grade, and who relied on market-based finance, could face difficulty accessing funding, given many investors’ mandates were constrained by credit ratings. The interaction of high sovereign debt and less resilient banks in Japan and some European economies was also seen as a risk. However, in the United States and the United Kingdom, the resilience of the banking system had increased as profitability had improved.

Corporate debt in China had increased sharply over the previous decade, although in relation to GDP it had declined recently in response to policy measures to promote deleveraging. These measures included closing some unprofitable state-owned firms, restructuring some debt, reducing the size of non-bank financing and reducing non-banks’ interactions with banks.

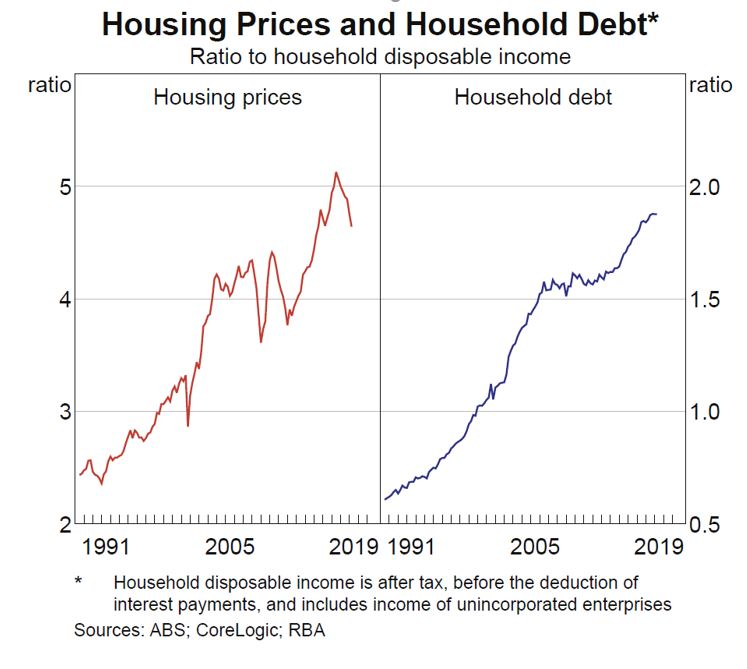

In Australia, near-term risks related to the housing market had eased in the preceding few months with a turnaround in housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne. Prices in those cities had fallen by a little under 10 per cent over the preceding 18 months, reducing the housing equity of households and resulting in a small share with negative equity. The recent increase in housing prices in those cities had reduced the risk of large increases in negative equity, which could result in losses for lenders if declines in income reduced households’ ability to meet debt repayments. Half of all loans in negative equity were in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, where housing price declines had persisted over the previous few years. Members noted that the rate of mortgage arrears in Western Australia had increased by more for riskier types of lending, including lending with smaller deposits, higher repayments relative to income, and loans to investors and self-employed borrowers.

Despite the high level of household debt in Australia relative to other countries, the risks from household debt appeared to be mostly contained. While the share of mortgages in arrears had continued to rise, it remained at a low rate relative to many other countries and in absolute terms. In addition, the quality of new lending had increased in recent years. The shares of loans with high loan-to-valuation ratios and with interest-only repayment terms had declined following a focus by regulators on this higher-risk lending. Further, members noted that households continued to have large prepayments on their housing debt. In aggregate, mortgage prepayments were equal to two-and-a-half years of repayments. However, while one-third of borrowers had prepayments exceeding two years of mortgage repayments, a slightly lower share had very little or no buffers. Of these, a little less than half appeared more likely to be vulnerable to shocks to their ability to meet their mortgage payments.

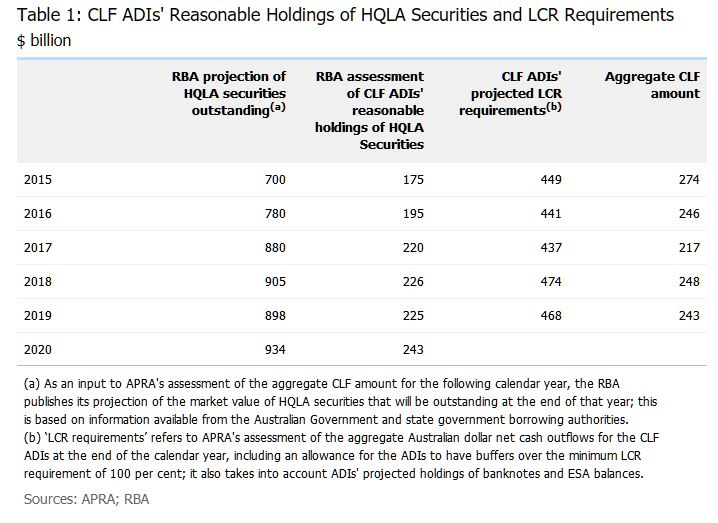

The resilience of Australian banks had increased since the financial crisis. Banks had largely completed their transition to their higher ‘unquestionably strong’ capital ratios. Banks’ resilience would increase further with the introduction by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority of a Loss Absorbing Capacity (LAC) regime, which will require banks to raise an additional 3 percentage points of capital by 2024. Members observed that banks were already issuing new Tier 2 securities to meet their LAC requirements. Banks’ profitability had declined a little over the prior year or two, although banks remained highly profitable. The increase in housing arrears had resulted in a small decline in banks’ overall asset quality, although asset quality remained high. Rates of non-performing business loans were a little below rates for housing loans.

Members also discussed non-financial risks facing the financial system. Members noted that cyber risks, and IT risks more broadly, were increasing as technology systems become more complex and embedded in all operations. Members also noted that climate change presented a risk to financial institutions. While extreme weather events were thought unlikely to produce large losses for the financial system as a whole, at least at present, losses could be larger in future if financial institutions do not manage the risks carefully.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

In considering the policy decision, members observed that the risks to the global growth outlook remained tilted to the downside. The trade and technology disputes between the United States and China were affecting international trade and investment, as businesses scaled back their spending plans in response to increased uncertainty. In China, the authorities had taken further steps to support the economy, while continuing to address risks in the financial system. In most advanced economies, inflation remained subdued despite low unemployment rates and rising wages growth.

In this context, global interest rates had continued to decline, with the central banks in the United States and Europe reducing interest rates in the previous month. Further monetary easing was widely expected, as central banks continued to respond to the downside risks to the global economy and subdued inflation. Long-term government bond yields were close to record lows in many countries, including in Australia. Borrowing rates for both businesses and households were at historically low levels, and the Australian dollar was at its lowest level in recent years.

Members considered the case for a further easing in monetary policy at the present meeting, to support employment and income growth and to provide greater confidence that inflation would be consistent with the medium-term target. Members noted that the Bank’s most recent forecasts suggested that the unemployment and inflation outcomes over the following couple of years were likely to be short of the Bank’s goals. The most recent run of data had not materially altered this assessment and, on balance, had been on the softer side. The ongoing subdued rate of wages growth also suggested that the economy still had spare capacity. There was therefore a case to respond to the general outlook with a further easing of monetary policy.

Members were mindful, however, that monetary policy was already expansionary and that the lower exchange rate was also supporting growth. They acknowledged that these factors and the recent tax cuts could combine to boost growth by more than their individual effects would imply, especially given the context of the mining and established housing sectors seeming to have reached turning points. At the same time, members recognised that it was possible that the effects may be smaller than expected and the global risks were to the downside.

Members also considered the argument that some monetary stimulus should be kept in reserve to address any future negative shocks. However, that argument requires changes in interest rates to be the key driver of demand, rather than the level of interest rates, which experience has shown to be the more important determinant. Members concluded that the Board could reduce the likelihood of a negative shock leading to outcomes that materially undershot the Bank’s goals by strengthening the starting point for the economy.

The Board’s discussions also focused on the ongoing strength in employment growth. The period of strong employment growth had not reduced spare capacity in the labour market significantly. Almost all of the strength in employment growth over the preceding three years had been matched by higher participation, so there had been little progress on reducing unemployment and underemployment. It was also possible that participation was rising partly in response to weak growth in incomes. Moreover, employment growth was forecast to slow over the period ahead.

Members also discussed the possibility that policy stimulus might be less effective than past experience suggests. They recognised that some transmission channels, such as a pick-up in borrowing or the effect on the home-building sector, may not be operating in the same way as in the past, and that the negative effect of low interest rates on the income and confidence of savers might be more significant. Notwithstanding this, transmission through the exchange rate channel was still considered likely to work effectively, and evidence suggested that the positive effects of lower interest rates on aggregate household cash flows via lower debt repayments was likely to support household spending, given that household interest payments exceed receipts by more than two to one.

Members also noted that the housing market and other asset prices might be overly inflated by lower interest rates. Members acknowledged that asset prices were part of the transmission mechanism of policy, including by encouraging home building. By themselves, higher asset prices were considered unlikely to present a risk to macroeconomic and financial stability. This assessment would need to be reviewed if rapidly increasing asset prices were accompanied by materially faster credit growth, weak lending standards and rising leverage. Although household debt was still considered high, members saw only a limited risk of excessive borrowing at the current juncture: household disposable income growth (and thus borrowing capacity) is weak; the memory of recent housing price falls is still fresh; and banks are still quite cautious in their appetite to lend. Nonetheless, members assessed that close monitoring of this risk was warranted.

Members concluded that these various factors did not outweigh the case for a further easing of monetary policy at the present meeting. Taking into account all the available information, including the reductions in interest rates since the middle of the year, the Board decided to lower the cash rate by a further 25 basis points. Members judged that lower interest rates would help reduce spare capacity in the economy by supporting employment and income growth and providing greater confidence that inflation would be consistent with the medium-term target. Members also noted the trend to lower interest rates globally and the effect this was having on the Australian economy and inflation outcomes.

Members judged it reasonable to expect that an extended period of low interest rates would be required in Australia to reach full employment and achieve the inflation target. The Board would continue to monitor developments, including in the labour market, and was prepared to ease monetary policy further if needed to support sustainable growth in the economy, full employment and the achievement of the inflation target over time.

The Decision

The Board decided to lower the cash rate by 25 basis points to 0.75 per cent.