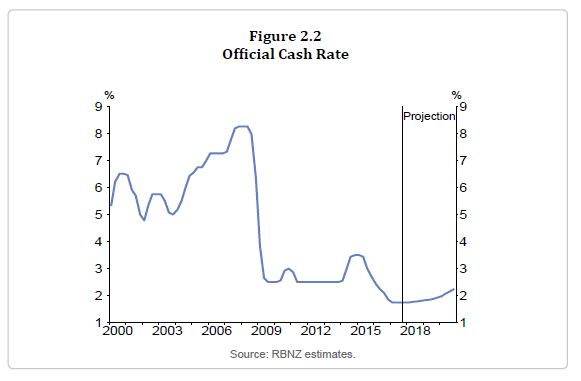

The New Zealand Reserve Bank today left the Official Cash Rate (OCR) unchanged at 1.75 percent. They are projecting higher rates ahead.

Global economic growth continues to improve, although inflation and wage outcomes remain subdued. Commodity prices are relatively stable. Bond yields and credit spreads remain low and equity prices are near record levels. Monetary policy remains easy in the advanced economies but is gradually becoming less stimulatory.

The exchange rate has eased since the August Statement and, if sustained, will increase tradables inflation and promote more balanced growth.

GDP in the June quarter grew broadly in line with expectations, following relative weakness in the previous two quarters. Employment growth has been strong and GDP growth is projected to strengthen, with a weaker outlook for housing and construction offset by accommodative monetary policy, the continued high terms of trade, and increased fiscal stimulus.

The Bank has incorporated preliminary estimates of the impact of new government policies in four areas: new government spending; the KiwiBuild programme; tighter visa requirements; and increases in the minimum wage. The impact of these policies remains very uncertain.

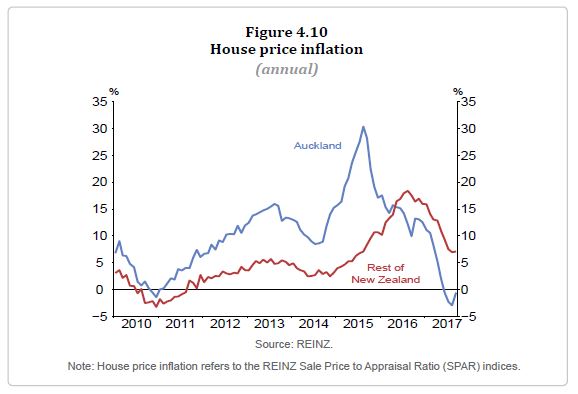

House price inflation has moderated due to loan-to-value ratio restrictions, affordability constraints, reduced foreign demand, and a tightening in credit conditions. Low house price inflation is expected to continue, reinforced by new government policies on housing.

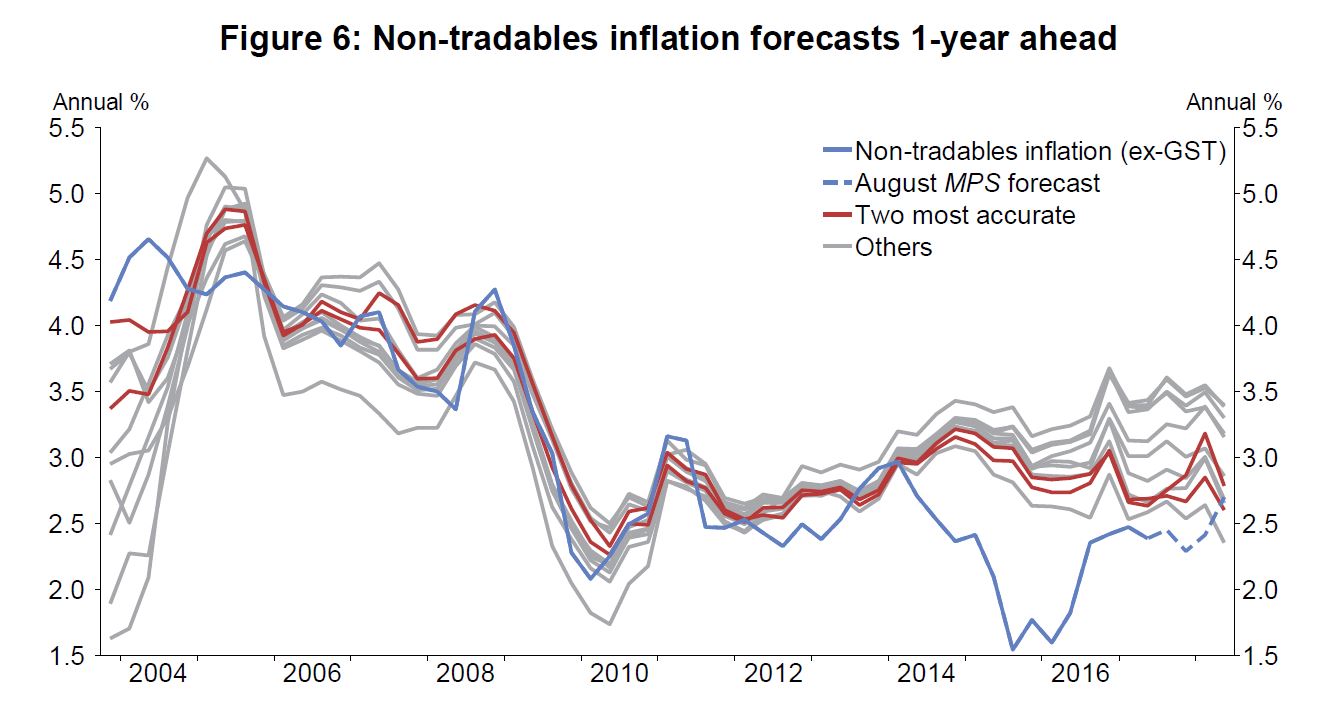

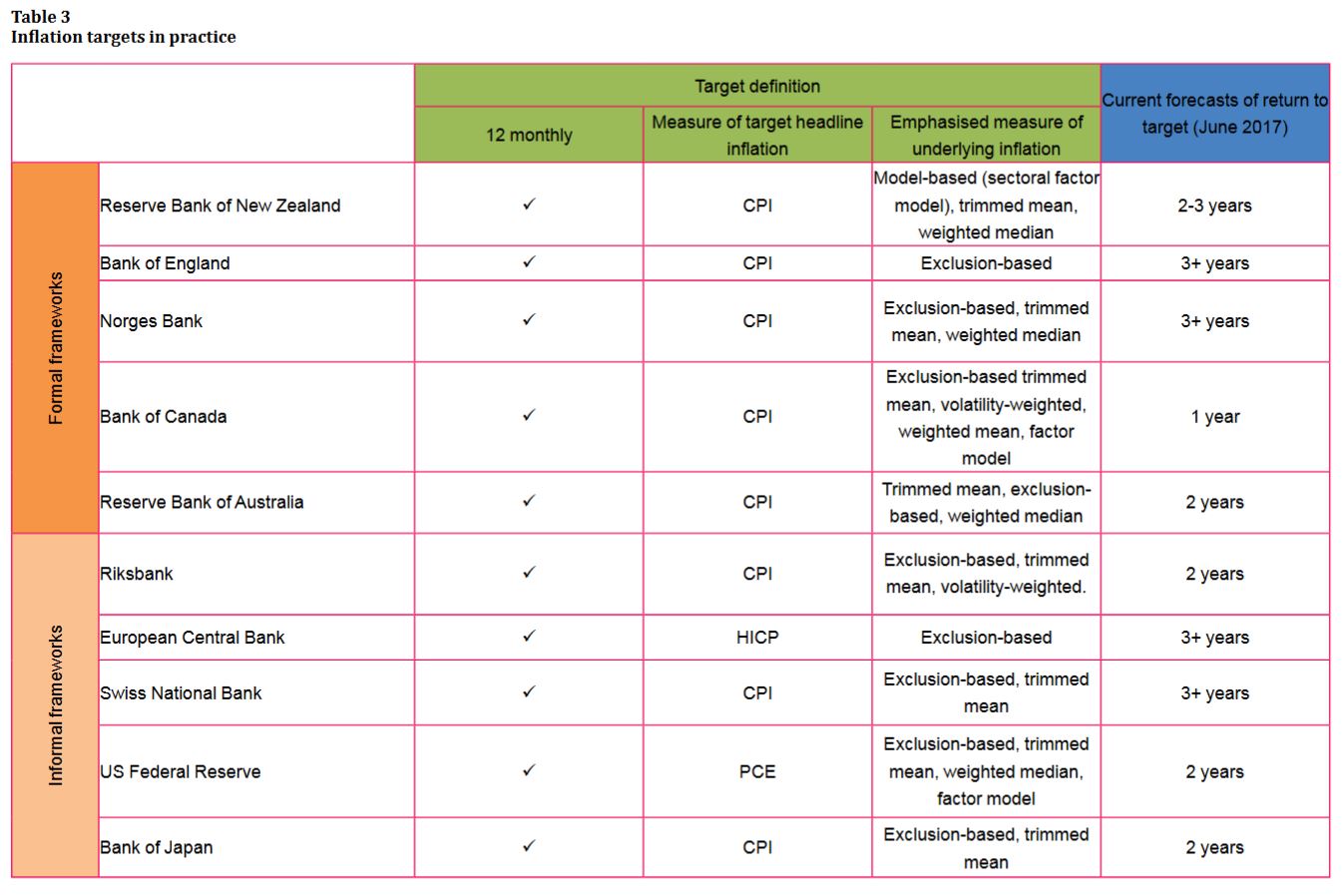

Annual CPI inflation was 1.9 percent in September although underlying inflation remains subdued. Non-tradables inflation is moderate but expected to increase gradually as capacity pressures increase. Tradables inflation has increased due to the lower New Zealand dollar and higher oil prices, but is expected to soften in line with projected low global inflation. Overall, CPI inflation is projected to remain near the midpoint of the target range and longer-term inflation expectations are well anchored at 2 percent.

Monetary policy will remain accommodative for a considerable period. Numerous uncertainties remain and policy may need to adjust accordingly.