The government has bent to calls from experts and Labor by clearing away the accounting impediments to a big spend on infrastructure.

In a speech on Thursday, his last before he hands down the May 9 budget, Treasurer Scott Morrison promised to change how the budget reports the deficit.

Instead of reporting the ‘underlying cash balance’ (which counts “good and bad debt”) prominently and burying the ‘net operating balance’ (which only counts “bad debt”), Mr Morrison said he will put them side by side from now on.

“While the net operating balance has been a longstanding feature of our budget papers … it has not been in clear focus. This change will bring us into line with the states and territories, who report on versions of the net operating balance, as well as key international counterparts including New Zealand and Canada.”

In this context, “good debt” is borrowings for economy-boosting capital expenditure, such as roads and trains that reduce the time it takes to get to work, while “bad debt” is borrowing to cover the cost of defence and welfare.

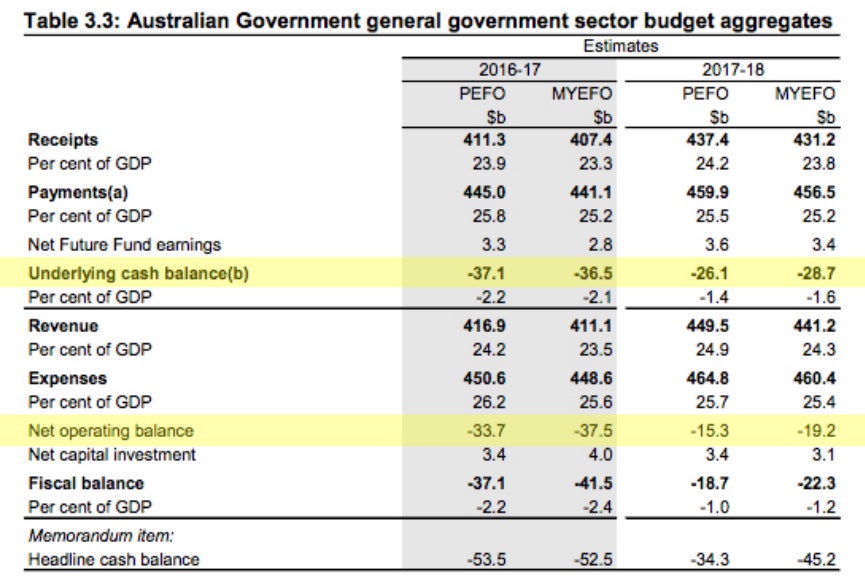

As an example, in the latest MYEFO budget update, the projected underlying cash deficit for 2017-18 was $28.7 billion but the net operating deficit was only $19.2 billion.

Mr Morrison’s pledge was a marked reversal on his comments late last year when he said the government would only take on “so-called good debt” for infrastructure spending once it had brought “bad debt” under control.

The Coalition will soon, perhaps in the next six months, be forced to administratively lift the $500 billion gross debt ceiling to allow the government to keep borrowing. Nevertheless, the government will heed the calls of experts for debt-fuelled stimulus.

Various expert bodies, including the Reserve Bank, have been prodding the government to take advantage of record-low borrowing costs to renew Australia’s public infrastructure.

In his farewell address, former RBA governor Glenn Stevens said the economy would only be pulled out if its malaise if “someone, somewhere, has both the balance sheet capacity and the willingness to take on more debt and spend”.

“Let me be clear that I am not advocating an increase in deficit financing of day-to-day government spending,” Mr Stevens said.

“The case for governments being prepared to borrow for the right investment assets – long-lived assets that yield an economic return – does not extend to borrowing to pay pensions, welfare and routine government expenses, other than under the most exceptional circumstances.”

Credit ratings agencies, the International Monetary Fund and the OECD have also encouraged infrastructure spending.

And in a discussion paper last year, Labor’s shadow finance minister Jim Chalmers called for consultation on the “optimal budget presentation for intelligent investment in productivity enhancing infrastructure assets” and the idea of splitting out “spending on productive economic assets such as infrastructure from recurrent expenditure”.

Labor took a very different line on Thursday, with Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen accusing the government of employing accounting “smoke and mirrors” to hide its economic mismanagement.

Anthony Albanese, the opposition’s infrastructure spokesman, welcomed the change but accused the government of wasting the last four years coming to the decision.

“Treasurer Scott Morrison’s declaration today that at a time of record low interest rates it makes sense to borrow for projects that boost economic productivity is precisely what Labor, the Reserve Bank and economists have been saying for years,” Mr Albanese said.

He warned the government’s “ill-advised” decision to create an infrastructure unit within the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, rather than relying on the independent Infrastructure Australia, risked pork barrelling.

“Creating another bureaucracy to sideline the independent adviser makes no sense. The government should have already learned that lesson from its creation of the Northern Australia Investment Facility, which was announced two years ago but has not invested in a single project.”