Many U.S. banks reported relative strength in consumer lending in fourth quarter earnings, while corporate lending growth was below expectations, according to Fitch Ratings‘ latest “U.S. Banking Quarterly Comment: 4Q17.”

The industry reported around 3% loan growth for the full-year, well below historical averages. With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), it’s unclear if there will be an uptick in lending with fewer incentives for U.S. corporates to borrow.

“Loan growth is expected to remain muted next year as many banks publicly disclosed they are targeting between low- and mid-single digit loan growth for the year,” said Julie Solar, Senior Director, Fitch Ratings.

Tax reform had a significant impact on fourth quarter earnings, but outside of one-time tax charges and gains, most banks reported improving spread income from interest rate increases, still benign credit costs, strong investment banking results and well-controlled core expenses. During earnings calls, many banks disclosed new earnings targets with improved returns. The large regional banks continue to report relatively stronger earnings than the universal banks, though not all banks included in the comment publicly disclosed new targets.

“The TCJA created a lot of noise in the quarter, but going forward most banks will likely report a boost to earnings,” added Solar.

Costs of credit continue to fall well below long-term average with net charge-offs at historically low levels across many asset classes, averaging 44bps during the quarter. This is well below the industry historical average since 1984 of nearly 80bps (which excludes financial crisis era losses between 2008-2010).

The five U.S. Global Trading and Universal Banks (GTUBs) reported strong investment banking and weak trading results during the fourth quarter of 2017 (4Q17), a trend that is unlikely to reverse anytime soon, according to Fitch Ratings’ “U.S. Capital Markets Quarterly: 4Q17“. Growth in debt underwriting from a strong leveraged finance market, an increase in equity underwriting, and growth in advisory drove investment banking (IB) results higher. However, total capital markets revenues in 4Q17 were $22.12 billion; a decline of 10.97% year over year due to weakness in fixed income, currencies and commodities (FICC) net revenue as client engagement levels fell across multiple products.

“Low volatility is problematic for trading, but it does allow corporates to plan for M&A activity which boosts investment banking results,” said Justin Fuller, Senior Director, Fitch Ratings. “Though, the correlation between guidance during earnings calls and future revenue is weak as economic and political variables can often delay deal execution.”

Overall 4Q17 IB revenues were the best fourth- quarter performance in the past five years, with total IB revenues of $8.1 billion, up 19.2% year over year. Overall 4Q17 FICC revenues for all of the U.S. GTUBS declined 30.7% from the prior year to $8.2 billion as continued low volatility drove low levels of client activity.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPM) retained its leading market share position with 23.2% of overall capital markets revenues in 4Q17; however, its overall share declined by 150 basis points year over year, while Bank of America (BAC) achieved year over year share gains of 190 basis points. As a result, the shares of Morgan Stanley (MS), BAC and Citigroup (C) converged at just less than 19% of total capital market fees in 4Q17.

In 4Q17, capital markets revenue as a percentage of total revenue decreased for each firm on a year over year basis. The average contribution to overall revenues of the five U.S. GTUBs was 22.1% in 4Q17, down from 24.9% in the prior year quarter. However, the contribution from capital markets revenue in 4Q17 is only slightly below the five-year average of fourth-quarter capital markets revenue of 22.5%. The five U.S. GTUBs all had significantly higher net interest income this quarter due to higher year over year short-term interest rates as well as incrementally higher wealth/asset management revenues amid higher global equity markets. Fitch believes the strength of these other sources of revenue helps to demonstrate the diversity of the business models of some of the larger banks.

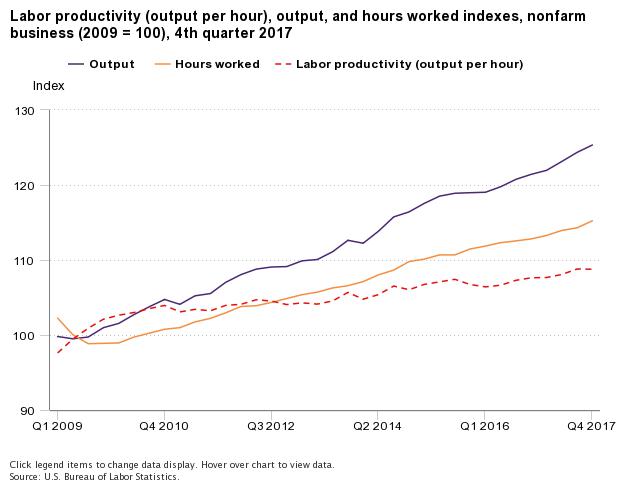

From the fourth quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2017, nonfarm business sector labor productivity increased 1.1 percent, reflecting a 3.2-percent increase in output and a 2.1-percent increase in hours worked. Annual average productivity increased 1.2 percent from 2016 to 2017.

From the fourth quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2017, nonfarm business sector labor productivity increased 1.1 percent, reflecting a 3.2-percent increase in output and a 2.1-percent increase in hours worked. Annual average productivity increased 1.2 percent from 2016 to 2017.