From The Conversation.

Data this week pointed to a continued shakiness in the Australian economy, while the robust US recovery continued.

In Australia, private-sector lending grew at just 0.3%, compared to 0.5% in August. Perhaps more worryingly, business lending dropped 0.1%. It was, again, housing credit growth that propped up the overall figures, growing 0.5% for the month.

Worse still, new home sales fell 6.1% in September, compared to August, according to the Housing Industry Association. So Australians aren’t borrowing much, except to finance the swapping around of each other’s houses at higher and higher prices. Note to picky readers: yes, prices fell a tiny bit in Sydney last month (0.1%), but are still up 10.5% year-on-year.

The US labour market bounced back from the hurricane season, adding 235,000 private sector jobs, according to data from payroll provider ADP. This wasn’t merely a bounce back — it exceeded expectations of a 200,000 gain. This was the biggest gain since March and further evidence of the strong US recovery.

It was not surprising, then, that Conference Board figures showed strong consumer confidence. What was striking, however, was just how strong those figures were. The confidence index rose to 5.3 points to 125.9 – the highest since December 2000. The present conditions measure was also at its highest level since 2001.

The US Federal Reserve kept interest rates on hold at a band of 1.0-1.25% at this week’s meeting, but signalled a fairly high likelihood of a rate rise when they meet in December. As the statement put it:

The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant gradual increases in the federal funds rate.

Perhaps the only real wrinkle is that inflation remains stubbornly low, despite unemployment being at 4.2%. Some measures of inflation expectations are rising, so the best bet is for a 25 basis point rise in December.

The Fed’s statement made pretty explicit how they think about balance these factors, stating:

the Committee continues to expect that, with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace, and labor market conditions will strengthen somewhat further. Inflation on a 12-month basis is expected to remain somewhat below 2 percent in the near term but to stabilize around the Committee’s 2 percent objective over the medium term.

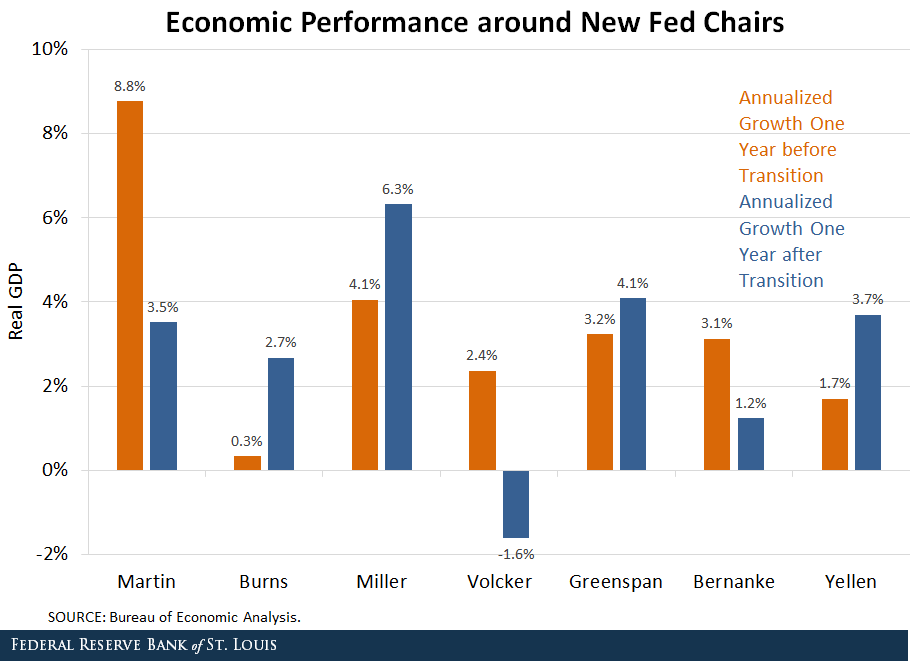

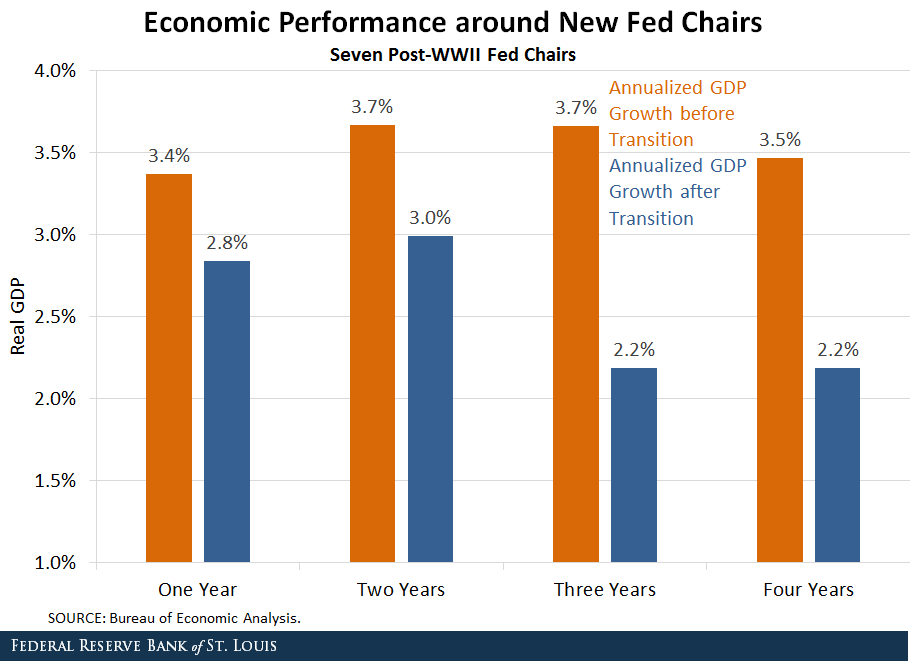

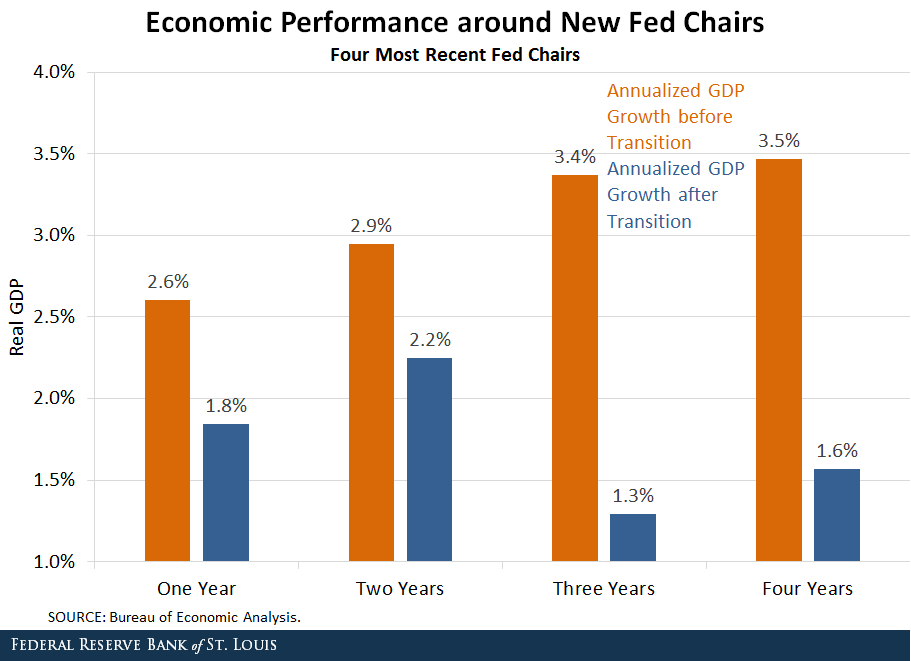

Of course, current Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s term concludes in February next year, and it is being widely reported that President Trump will not reappoint her. Rather he seems set (to the extent that is possible with him) to appoint Jay Powell as Chair.

I will have more to say about that in future columns, but the main thing to note here is that Powell is extremely likely to continue with the path of monetary policy that Yellen has laid out.

So why is it that the US – which suffered a major downturn – seems to have a stronger economy than Australia – which did not even go into recession in 2008-09?

One view is that the US went through a process of Schumpetarian “creative desctruction”. Homeowners who couldn’t afford their properties got foreclosed on, investment banks that weren’t viable went bust, and the rest of the financial system was recapitalised.

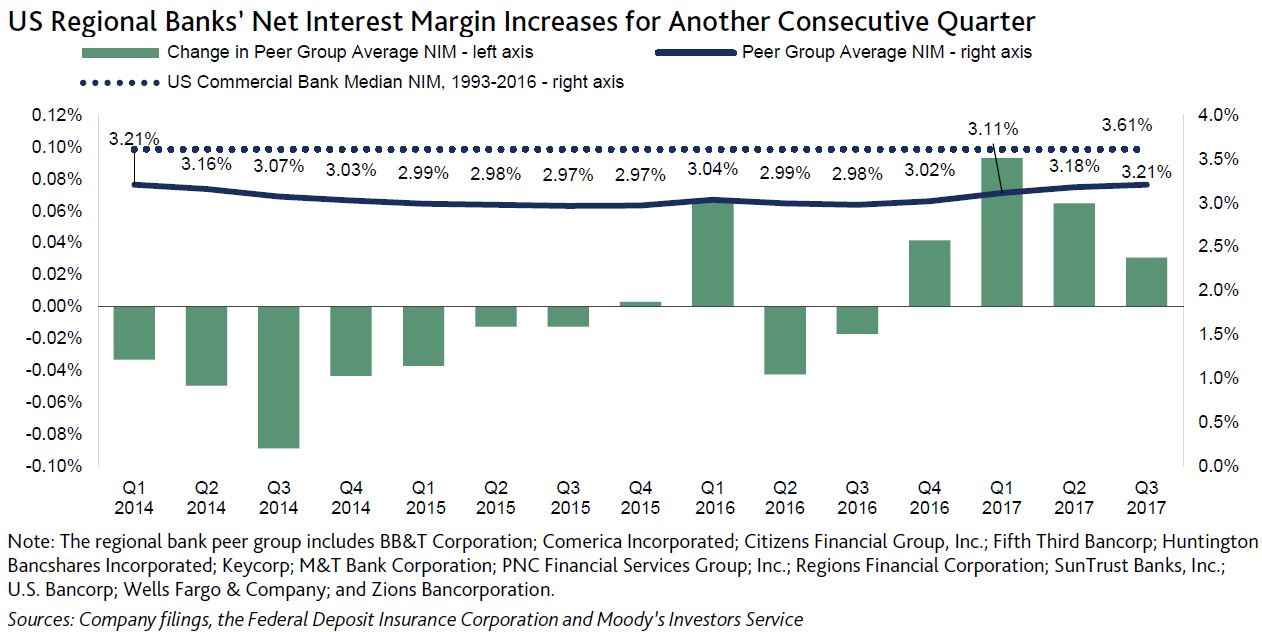

Australian banks, by contrast have made some progress in getting their funding structure to be less short-term and dependent on US capital markets – but only so much. And it seems quite possible that they continue to make questionable loans – particularly interest-only loans – as I wrote about here, and spoke about here.

A second view is that the US economy is better able to adapt to the changing nature of the modern economy. It has much more flexible labour markets – although much harsher and less rewarding for average workers.

Perhaps it is neither of these, but presumably both the Reserve Bank and Treasury are trying to understand what looks like a striking different between the US and Australian experiences.

Author: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics and PLuS Alliance Fellow, UNSW