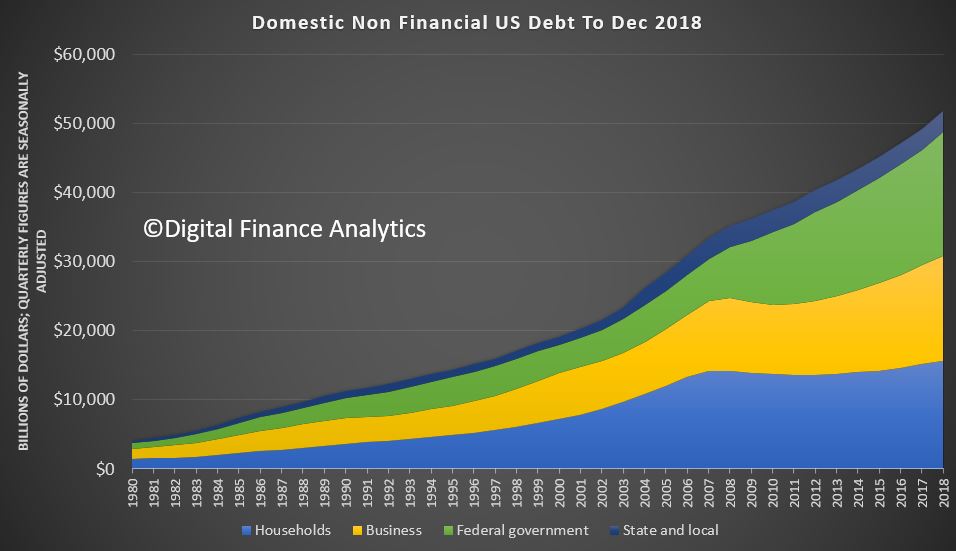

Moody’s says that US debt continues to rise (with strongest growth in the public sector) and a powerful enough external shock could force U.S. benchmark interest rates up to levels that shrink business activity considerably.

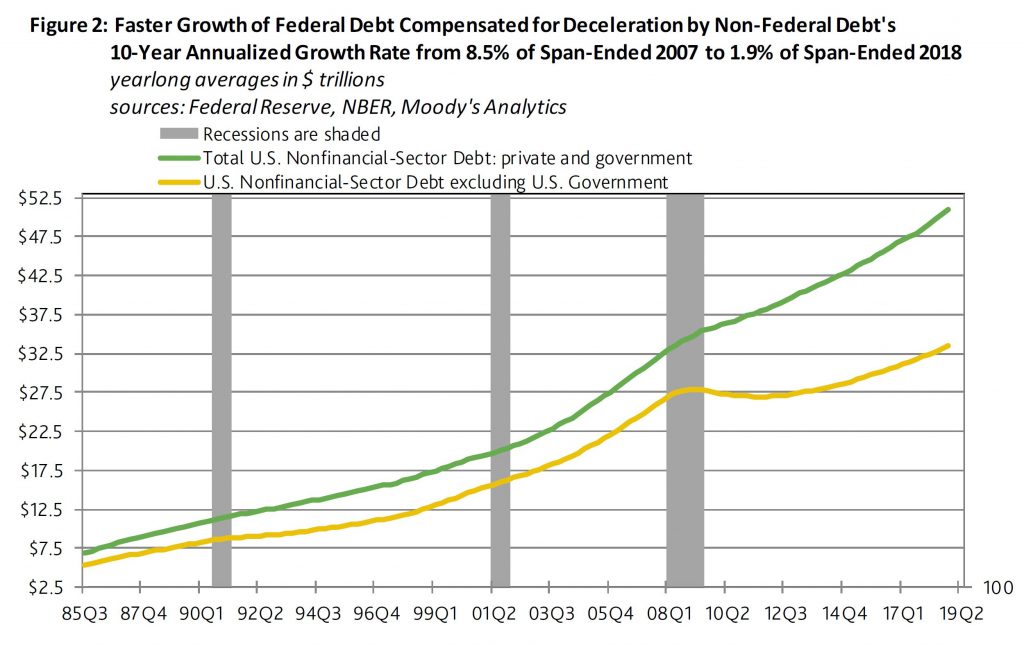

The latest version of the Federal Reserve’s “Financial Accounts of the United States” was released on March 7. As of 2018’s final quarter, the total outstandings of private and public nonfinancial-sector debt grew by 5.1% year-to-year to a record high $51.796 trillion. The year growth rate of the broadest estimate of U.S. nonfinancial-sector debt has slowed from second-quarter 2018’s current cycle high of 5.6%. Since the end of the Great Recession, the 3.9% average annualized rise by nonfinancial-sector debt

has slightly outpaced nominal GDP’s accompanying 3.7% average annual increase.

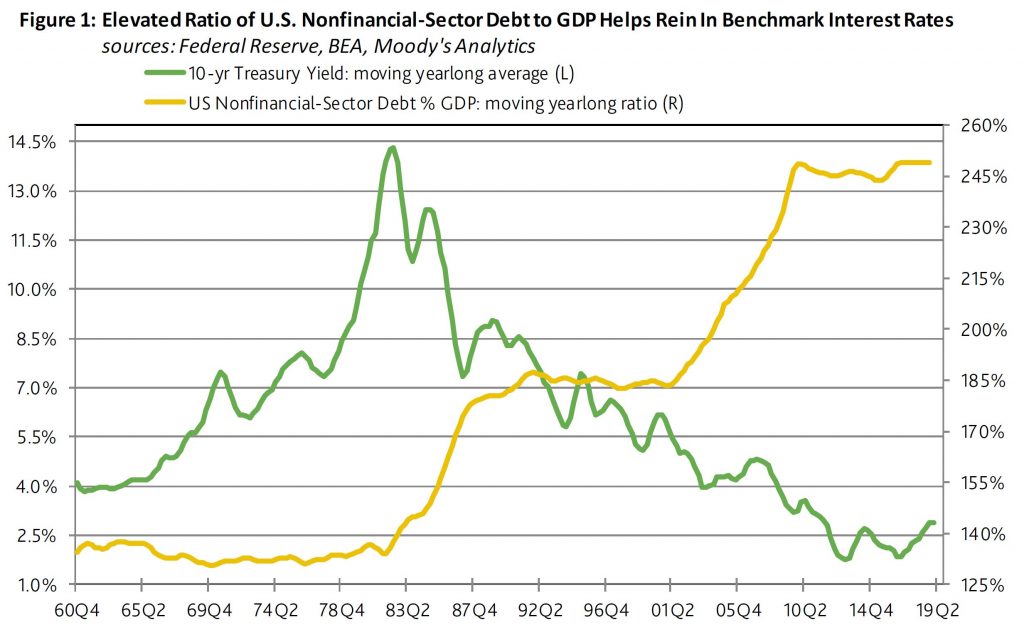

By contrast, during 2002-2007’s upturn, the 8.1% average annualized advance by nonfinancial-sector debt was much faster than nominal GDP’s comparably measured growth rate of 5.3%. As a result, the moving yearlong ratio of total nonfinancial-sector debt to GDP climbed from the 197% of 2001’s final quarter to the 225% of 2007’s final quarter. Because of the current recovery’s much slower growth of debt vis-a-vis GDP, debt barely rose from second-quarter 2009’s 243% to fourth-quarter 2018’s 249% of

GDP.

Today’s near record high ratio of nonfinancial-sector debt to GDP limits the upside for benchmark interest rates. Just as highly leveraged businesses exhibit a more pronounced sensitivity to higher benchmark interest rates, highly leveraged economies are likely to slow more quickly in response to an increase by benchmark rates. Relatively low interest rates do much to lessen the burden implicit to a comparatively high ratio of debt to GDP.

Nevertheless, a powerful enough external shock could force U.S. benchmark interest rates up to levels that shrink business activity considerably. Under this scenario the Fed would be compelled to hike rates in defense of the dollar exchange rate despite how a deterioration of domestic business conditions requires lower rates.

The federal government has dominated the growth of total nonfinancial-sector debt during the current business cycle upturn. In terms of moving yearlong averages, U.S. government debt’s 9.3% average annualized surge has well outrun the accompanying 2.2% growth rate for the sum of private and state and local government nonfinancial-sector debt.

Regarding 2018’s final quarter, the outstandings of U.S. government debt advanced by 7.6% annually to $217.865 trillion. By comparison, household-sector debt rose by 3.1% to $15.628 trillion, nonfinancial corporate debt increased by 6.5% to $9.759 trillion, unincorporated business debt grew by 4.9% to $5.485 trillion, while state and local government debt shrank by 1.7% to $3.060 trillion. Thus, fourth quarter 2081’s U.S. nonfinancial-sector debt excluding the obligations of the federal government grew by a modest 3.9% annually. Over the past 10-years, the faster growth of federal government debt compensated for the sluggish debt growth of non-federal borrowers.