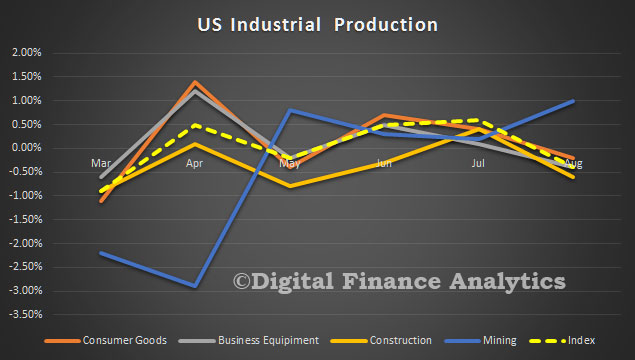

Latest figures from the US Federal Reserve shows that industrial production decreased 0.4 percent in August after rising 0.6 percent in July. The market reacted to this data, taking it as an indicator that a rate rise was less likely in the short term.

Manufacturing output declined 0.4 percent in August, reversing its increase in July; the level of the index in August is little changed from its level in March. Following two consecutive monthly increases, the index for utilities fell back 1.4 percent in August. Even so, the index was 1.7 percent above its year-earlier level, as hot temperatures this summer boosted the usage of air conditioning.

The output of mining moved up 1.0 percent in August, its fourth consecutive monthly increase following an extended downturn; the index, however, was still about 9 percent below its year-ago level. At 104.4 percent of its 2012 average, total industrial production in August was 1.1 percent lower than its year-earlier level. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector decreased 0.4 percentage point in August to 75.5 percent, a rate that is 4.5 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2015) average.

Market Groups

The indexes for all major market groups declined in August. The output of consumer goods decreased 0.2 percent as a result of a large drop in consumer energy products and a small decline in consumer non-energy nondurables. The output of consumer durables was unchanged; a gain in automotive products was offset by declines in all of its other components. Business equipment posted a decrease of 0.4 percent, as gains of 1 percent or more for transit equipment and for information processing equipment were outweighed by a cutback of nearly 2 percent for industrial and other equipment. The output of defense and space equipment declined 0.6 percent. The indexes for construction supplies and business supplies moved down 0.6 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively. The production of materials decreased 0.5 percent: Both durable and energy materials posted declines, while the output of nondurable materials was unchanged. The reduction in the index for durable materials reflected similarly sized losses across all its major categories.

Industry Groups

Manufacturing output declined 0.4 percent in August; the index was also 0.4 percent below its level of a year earlier. In August, the production of nondurables moved down 0.2 percent, and the indexes for durables and for other manufacturing (publishing and logging) fell 0.6 percent and 0.7 percent, respectively. Many durable goods industries posted declines of nearly 1 percent or more, with the largest drop, 1.9 percent, recorded by machinery. Within nondurables, gains for food, beverage, and tobacco products and for paper were more than offset by declines elsewhere; the largest decrease, 2.1 percent, was recorded by textile and product mills.

The index for mining moved up 1.0 percent in August, with a decline in coal mining outweighed by increases in the indexes for oil and gas extraction, for oil well drilling and servicing, and for metal ore and nonmetallic mineral mining.

Capacity utilization for manufacturing decreased 0.4 percentage point in August to 74.8 percent, a rate that is 3.7 percentage points below its long-run average. The operating rate for nondurables moved down 0.2 percentage point; the rates for durables and for other manufacturing (publishing and logging) each declined 0.5 percentage point. The operating rate for mining moved up 1.0 percentage point to 76.2 percent, while the rate for utilities decreased 1.3 percentage points to 80.4 percent.