New research from Juniper highlights the challenges and opportunities facing retail banks as digital migration moves fast, and branches become less relevant. “Mobile first” strategies are developing.

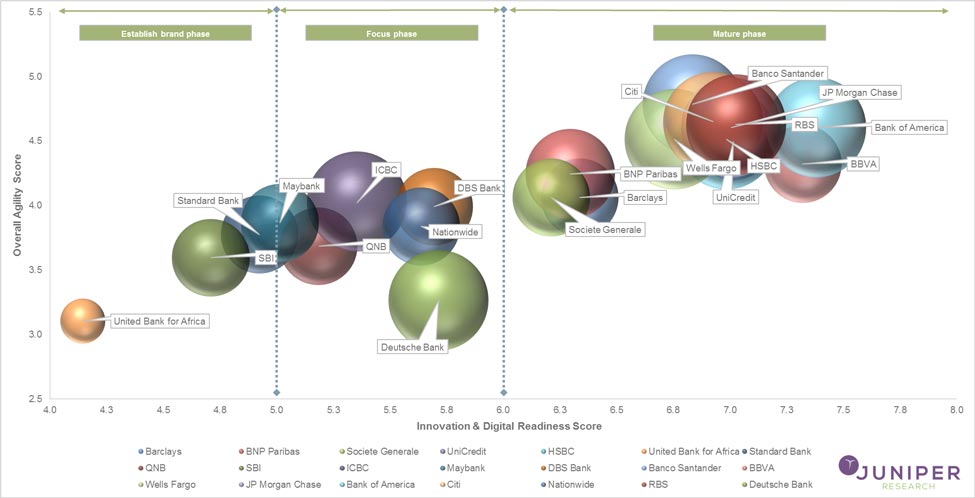

Juniper has analysed some of the leading Tier 1 banks from different parts of the world to evaluate their digital transformation readiness score and show their positioning to achieve the next level growth and digital innovation.

Juniper’s Readiness Index is designed to compare how these Tier 1 banks have scored based on the above mentioned target areas: relative placement of the banks in different phases does not necessarily mean that they are in anyway underperforming in terms of customers or revenue generation.

While most consumers, especially in developed markets, prefer digital banking and virtual channels, a significant proportion of consumers still prefer an in-branch session compared to an audio or video call with the customer contact centre. Juniper notes while this continued to be the case in the past 12 months, it will change as banks finalise a ‘balancing act’ between multiple channels.

This is more likely to be centred on the mobile device as banks move to a ‘mobile first’ approach, a trend supported by the scale of declining workforces and the number of physical branches, alongside increasing mobile usage across all markets.

Retail banks across the globe are struggling, with a report by the Bank of England in the UK highlighting that 30-40% of banks’ costs is concerned with running physical branches. However banks’ customers are not visiting their branches; in fact the report also found that footfall has fallen by 10% per annum.

This has been further confirmed by the decreasing number of branch visits by consumers and also the closure of physical bank branches over the past 12-24 months in other markets. In 2014, the number of US branches declined by 2% with only 2 banks amongst the top 12 (Wells Fargo and US Bancorp) increasing their branch numbers in that year.

The situation is rather different in emerging markets, such as China and India, where the number of physical banks is increasing in tandem with digital adoption. This is part of a wider trend in these markets to address a historic underdevelopment of physical banked infrastructure in rural areas and lower penetration of banked individuals. The growth in the banked population is particularly marked in India, rising from 30% of adults in 2010 to 48% by mid 2016. Nevertheless, even here, the focus is increasingly on digital expansion, especially in terms of digital wallets.Banking and payments markets have witnessed an array of new methods of providing services. This means that banks and VCs (Venture Capitalists) are increasingly investing in technology to drive continued innovation.

Banks are investing in technology firms partnering, as well as acquiring, some of the tech-first players, alongside setting up technology hubs and development centres. In fact, as the chart below suggests VC investments in fintech start-ups reached record levels in 2015, almost $14 billion.Meanwhile some of the more recent investment announcements by Tier 1 banks include:

- In mid 2016, Deutsche Bank announced that it will invest €750 million ($790 million) in developing digital products and advisory services by2020; nearly €200 million ($211 million) is expected to have been invested in 2016.

- In 2014, Spanish bank BBVA announced a $1.2 billion investment in technology projects in South America to boost its digital innovation in the market. Following that, in 2015, the bank invested $68 million in the UK-based challenger bank Atom for a 29.5% stake.

- In 2015, Lloyds Bank first announced its plan to invest £1 billion ($1.2 billion) in digital banking capability over the next 3 years. Previously, in the UK, RBS had announced a similar level of investment into digital technology and services development. Australian bank Westpac meanwhile announced that it will increase its annual investment spend by 20% to $1.3 billion, the majority of which will be dedicated to technology, digital and simplification projects.

- Indian bank SBI (State Bank of India) raised its IT budget in 2015 by a third to ₹4,000 crores ($580 million) as part of its strategy to improve its digital offerings. For the financial year ended March 2015, the bank had spent over ₹3,000 crore ($440 million) on technology.

- In 2016, ING first announced its plan to invest €800 million ($845 million) in digital transformation initiatives over the next 5 years. Meanwhile, Emirates NBD announced Dh500 million ($136 million) investment over the next 3 years on digital innovation and the multichannel transformation of its processes, products and services.

- Also in 2016, the Bank of Ireland announced its plans to invest €500 million ($588 million) in upgrades to its core IT infrastructures over the next 5 years.