From The Conversation.

[Insurance] is the one thing I will not skimp on, because we don’t know what’s around the corner with my husband being unwell and a disabled son. And now I’ve hurt my foot. I mean, accidents happen. I don’t know what’s around the corner. That’s the first thing that gets paid.

Maggie (all names in this article are psuedonyms), is a single woman in her 50s who lives with her husband and son with disability. She feels health insurance is essential to prepare for seemingly inevitable risks.

To afford insurance, Maggie cuts down on expenses by not buying clothes; she gets free clothes from charity organisations. She also saves money by only purchasing the cheapest marked-down foods that will expire soon and avoiding public transport to save money. And when things are tight she skips meals to make do.

To afford insurance, Maggie cuts down on expenses by not buying clothes; she gets free clothes from charity organisations. She also saves money by only purchasing the cheapest marked-down foods that will expire soon and avoiding public transport to save money. And when things are tight she skips meals to make do.

Some people on low incomes put insurance cover first – even if it means doing without basic goods, our research finds. Yet low-income households are the most likely to lack private insurance cover.

Insecure work, low and unstable incomes, and increasingly haphazard and unreliable social protections in education, health, transport and housing continue to make the lives of low-income households risky. Insurance can mitigate some of the harms low-income people face.

To understand how households with low or precarious incomes manage short and longer-term risks, we surveyed 70 people in three areas of suburban Melbourne that experience high levels of financial insecurity. We asked questions about household income and expenditure and how they coped with unexpected expenses.

We found that in order to pay for insurance people were cutting down on heating, food and outings.

Weighing up the odds

The financial problems faced by people on a low income are often explained by poor financial skills, knowledge and behaviours. Yet our research shows that low-income households are also constrained by uncertain and inadequate incomes, unaffordable housing and unexpected high energy costs.

Some of the people we surveyed weighed up their risk of serious incidents and went without insurance because the everyday risks they experienced were more pressing than potential future risks.

Ted, a single man in his fifties receiving the Newstart Allowance, would have liked to have insurance but explained that it was:

just cost prohibitive. I’d rather try and get a roof over my head…than being insured should something happen down the track.

Malcolm, a casually employed factory worker also receiving the Newstart Allowance, said his car was “not worth insuring” for property damage, even though not having insurance exposed him to risk if he damaged another person’s car.

It’s a financial balancing act. Most things that could get damaged on my car I could fix myself…It’s just unnecessary for me. And if it gets written off, it gets written off, and I move on.

Mending the safety net to reduce avoidable risks

Increasingly, private insurance is filling the gaps left by government policies. Instead of enduring the indignities of income support, people are encouraged to take out income protection insurance.

Private health insurance is promoted as a way of avoiding the queue for health care. Inadequate public transport means an increased reliance on private transport – with all the risks and costs that entails.

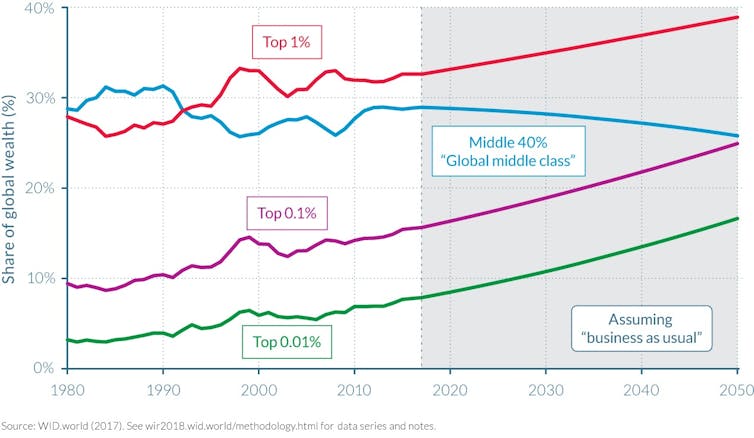

Insurance providers are aware of the increased risks of inequality. The data insurance companies gather provides fine grained information about the nature of risks to which individuals and insurance companies are exposed.

Research commissioned by the Actuaries Institute notes that because of this data gathering, a growing proportion of the population will be deemed so risky that the price of insurance will become too great for them.

Poor people who already lead risky lives will then be faced with even more risk. The Actuaries Institute report argues that there will be a greater need for government subsidised compulsory insurance to protect those who are exposed to risk beyond their control. But greater access to insurance isn’t the only answer.

Our research suggests that investment in the social safety net could reduce some of the avoidable risks that come with poverty. The government should be ensuring low-income households have access to adequate, predictable income; affordable, quality housing, accessible, affordable public transport and health care. All of these things reduce risks for individuals and contribute to a less divided and risky society.

Authors: Dina Bowman, Principal Research Fellow, Research & Policy Centre, Brotherhood of St Laurence and Honorary Senior Fellow, University of Melbourne; Marcus Banks, Senior Research Fellow, Work & Economic Security, Research & Policy Centre, Brotherhood of St Laurence. Social policy and consumer finance researcher, School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University