Last Wednesday, US regulatory agencies (namely the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission) jointly proposed changes to simplify and clarify the Volcker Rule and tailor the compliance obligations of US banks, based on their trading activities. The changes are based on several years of regulatory experience applying the Volcker Rule says Moody’s.

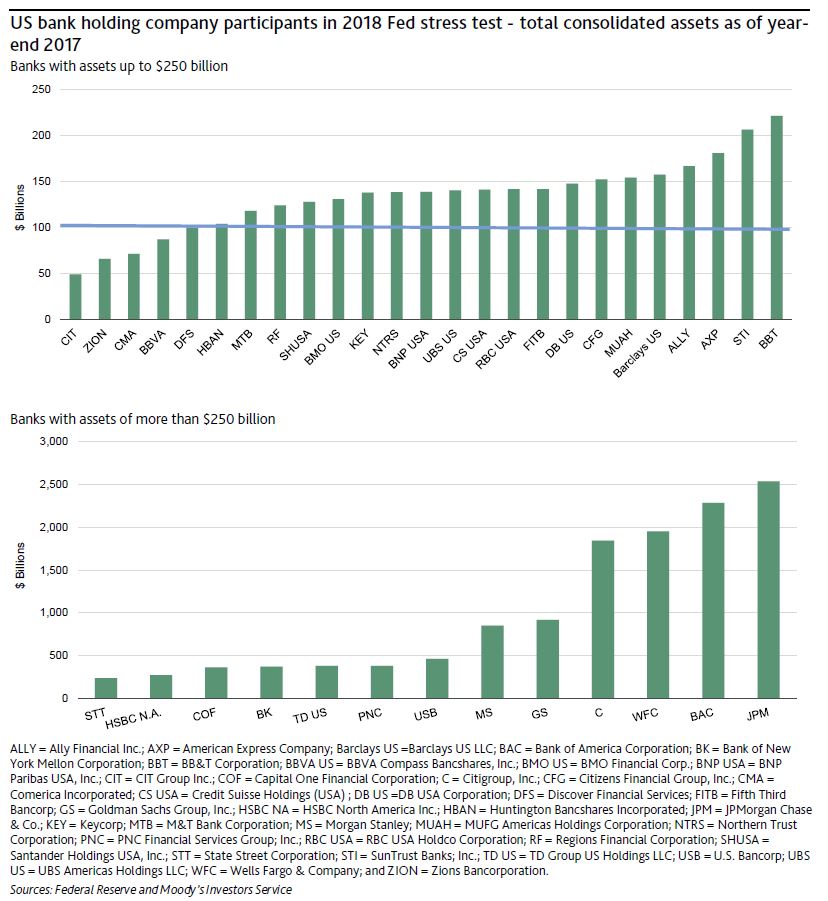

For banks with the most trading activity – including Bank of America Corporation, Citigroup Inc., The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo & Company – the proposed changes should reduce the uncertainty about the rule’s enforcement and simplify reporting requirements, which is credit positive for the banks.

The Volcker Rule will continue to prohibit most forms of proprietary trading, which it defines as purchasing or selling financial instruments (exempting of US government securities) with the intent to profit from short-term price movements.

There are three noteworthy proposed amendments to the Volcker Rule. First, to tailor the rule based on the degree of trading risk, banks will be divided into those with gross trading assets and liabilities exceeding $10 billion, those with between $1 billion and $10 billion and those with less than $1 billion – each with varying compliance requirements. The six aforementioned banks will all remain in the category with the most stringent reporting and compliance requirements.

Second, the definition of a trading account will be modified by replacing a “short-term intent” criterion with a more objective criteria that the account be recorded at fair value under applicable accounting standards. Finally, measurement of reasonably expected near-term demand (RENTD) is being modified. Under the existing rule, to be exempt from the ban on proprietary trading a bank must demonstrate that its purchase and sale of financial instruments relating to market-making and underwriting activities does not exceed RENTD. In practice, this has been difficult to demonstrate and may have contributed to banks’ reluctance to use the underwriting and market-making exemptions. Under the proposed amendments, a bank will be presumed to have stayed within RENTD if it implements, maintains and enforces internal risk limits surrounding its market-making and underwriting activities.

For the most active trading banks, added certainty about the provisos of the Volcker Rule should make it cheaper and easier to comply with the rule and provide greater certainty about allowable market-making and underwriting activities. At the same time, it may also make it easier for regulators to enforce the rule – and maintain a regulatory guardrail that protects creditors against the risk that banks drift into proprietary trading away from their core market-making activities.

A clarified Volcker Rule that is easier to comply with and enforce, when combined with other post-crisis regulatory enhancements that still require banks to hold greater amounts capital and liquidity for less liquid and more volatile exposures (including the Basel III capital and liquidity framework, the Dodd-Frank Stress Tests, and the Fed’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review), is a credit-positive development.