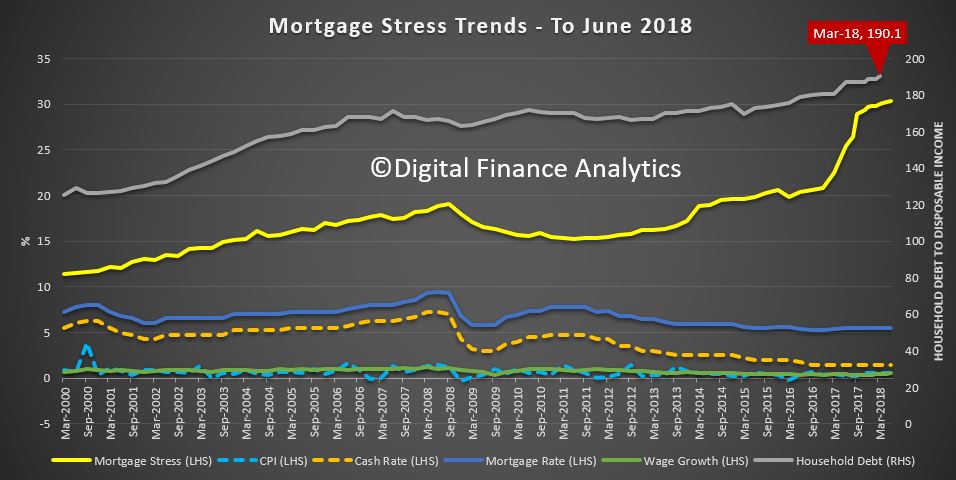

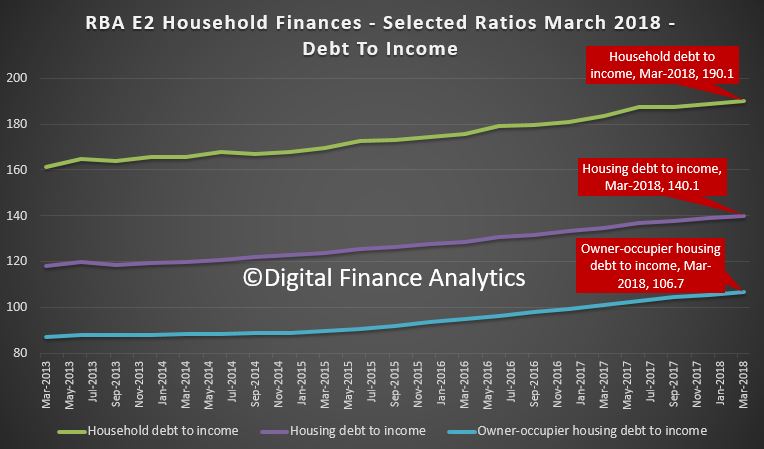

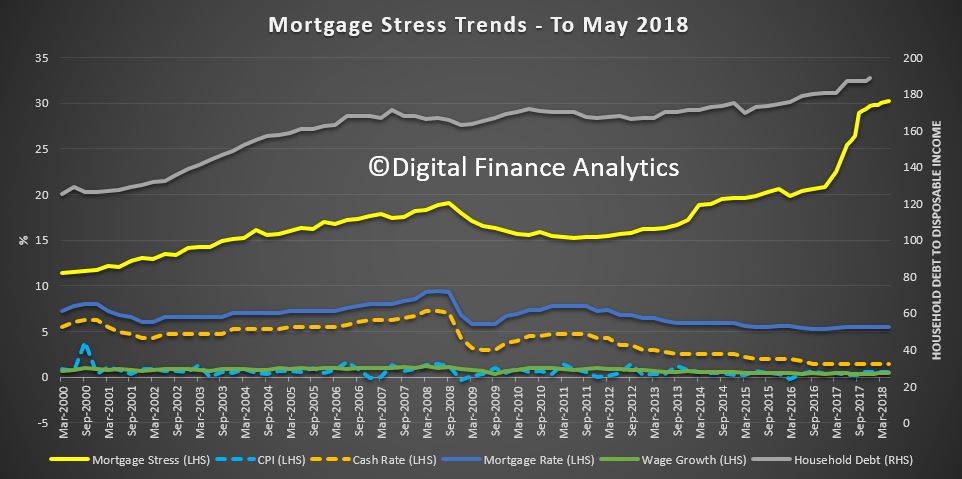

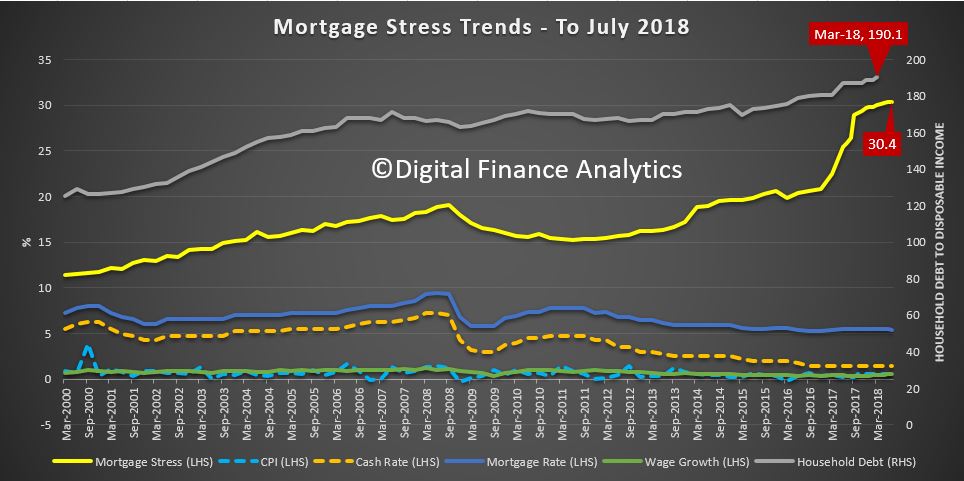

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) has released the July 2018 mortgage stress and default analysis update. The latest RBA data on household debt to income to March reached a new high of 190.1[1], and CBA today said in their results announcement ”there has been an uptick in home loan arrears as some households experienced difficulties with rising essential costs and limited income growth, leading to some pockets of stress”.

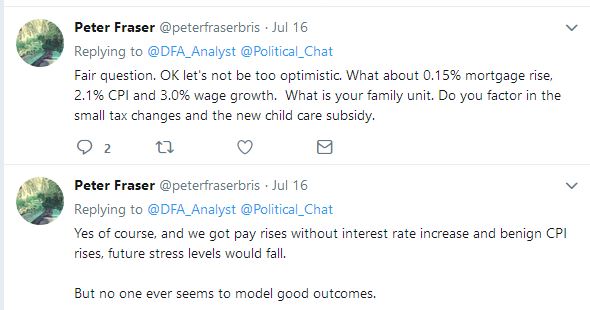

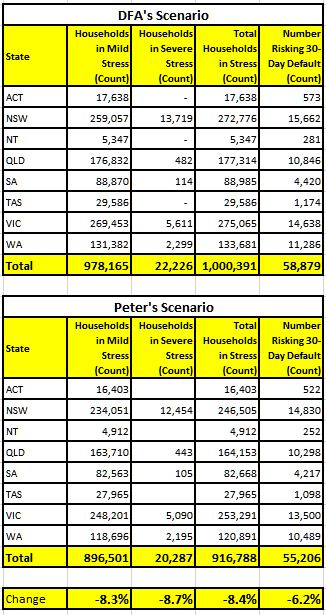

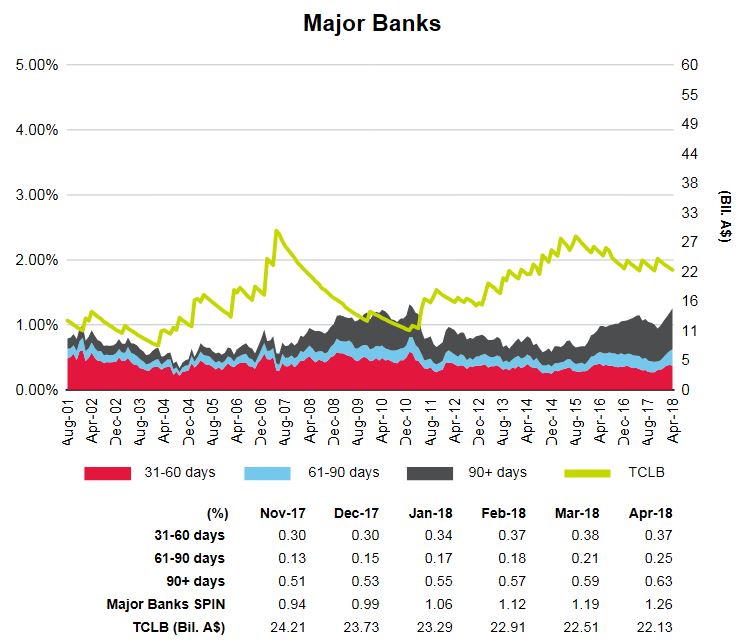

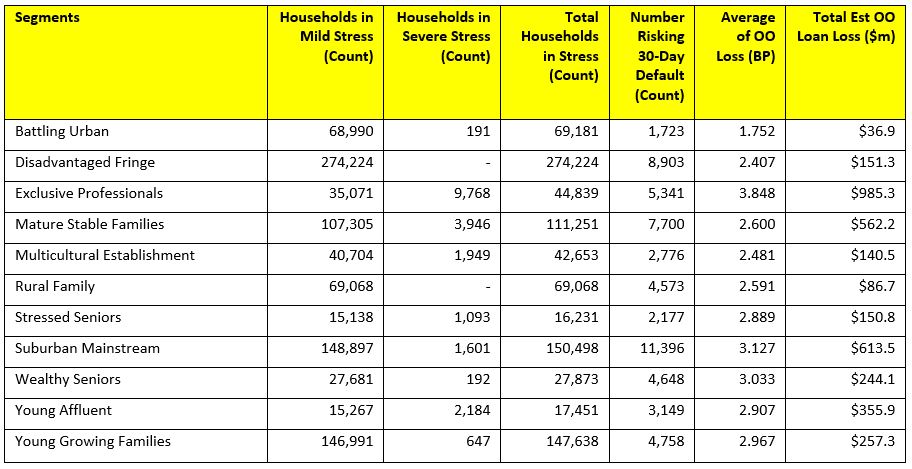

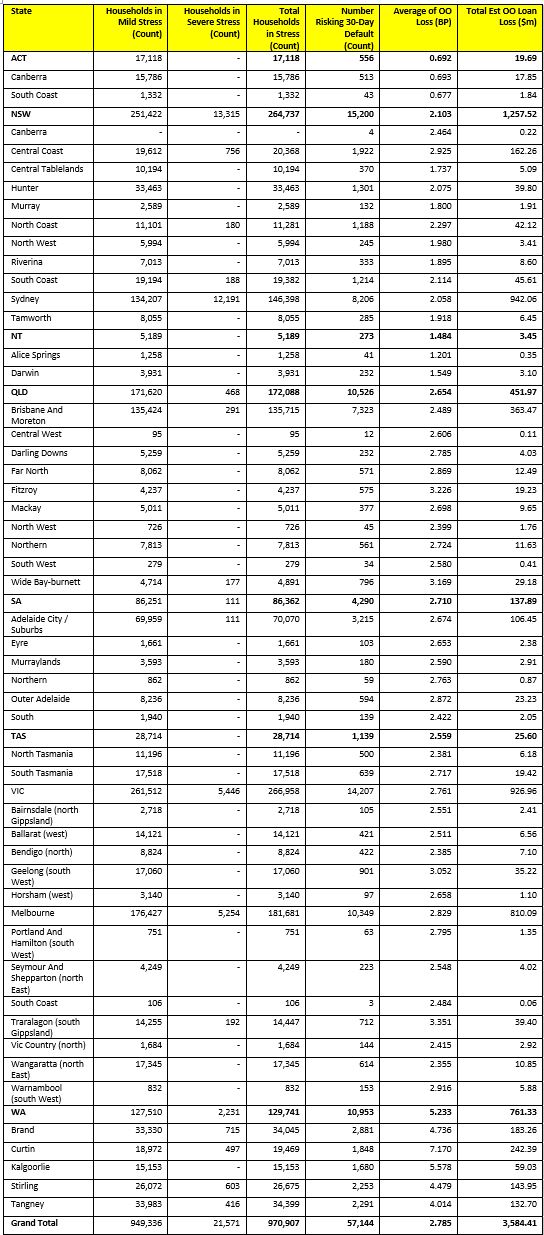

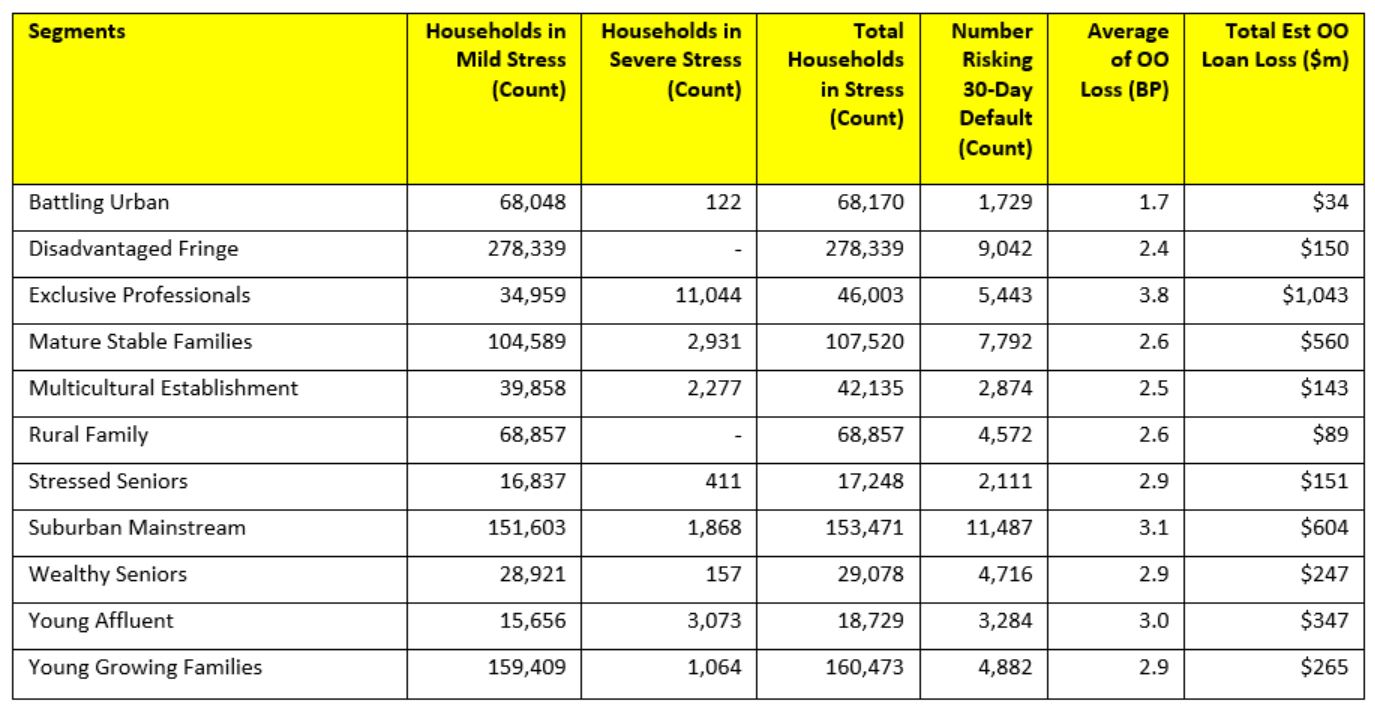

So no surprise to see mortgage stress continuing to rise. Across Australia, more than 990,000 households are estimated to be now in mortgage stress (last month 970,000). This equates to 30.4% of owner occupied borrowing households. In addition, more than 23,000 of these are in severe stress. We estimate that more than 57,900 households risk 30-day default in the next 12 months. We expect bank portfolio losses to be around 2.7 basis points, though losses in WA are higher at 5.1 basis points. We continue to see the impact of flat wages growth, rising living costs and higher real mortgage rates.

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics says “households remain under pressure, with many coping with very large mortgages against stretched incomes, reflecting the over generous lending standards which existed until recently. Some who are less stretched are able to refinance to cut their monthly repayments, but we find that the more stretched households are locked in to existing higher rate loans”.

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics says “households remain under pressure, with many coping with very large mortgages against stretched incomes, reflecting the over generous lending standards which existed until recently. Some who are less stretched are able to refinance to cut their monthly repayments, but we find that the more stretched households are locked in to existing higher rate loans”.

“Given that lending for housing continues to rise at more than 6% on an annualised basis, household pressure is still set to get more intense. In addition, prices are falling in some post codes, and the threat of negative equity is now rearing its ugly head”.

“The caustic formula of coping with rising living costs – notably child care, school fees and fuel – whilst real incomes continue to fall and underemployment is causing significant pain. Many households have larger mortgages, thanks to the strong rise in home prices, especially in the main eastern state centres, and now prices are slipping. While mortgage interest rates remain quite low for owner occupied borrowers, those with interest only loans or investment loans have seen significant rises. Many are dipping into savings to support their finances.”

“The caustic formula of coping with rising living costs – notably child care, school fees and fuel – whilst real incomes continue to fall and underemployment is causing significant pain. Many households have larger mortgages, thanks to the strong rise in home prices, especially in the main eastern state centres, and now prices are slipping. While mortgage interest rates remain quite low for owner occupied borrowers, those with interest only loans or investment loans have seen significant rises. Many are dipping into savings to support their finances.”

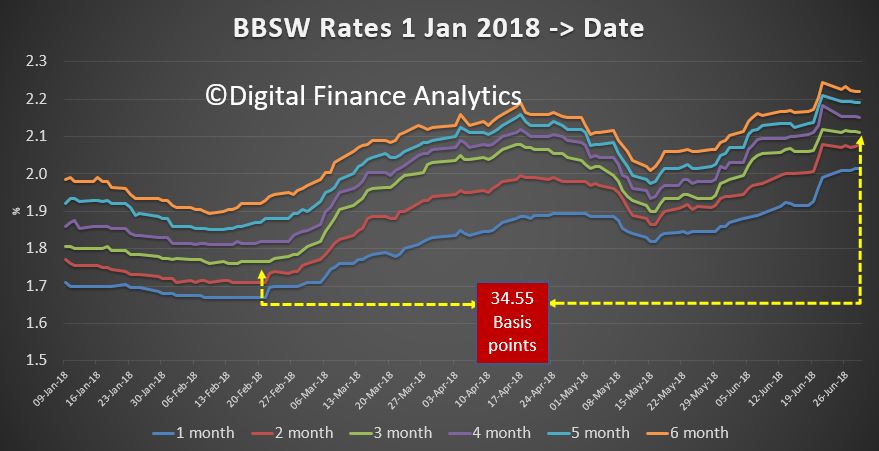

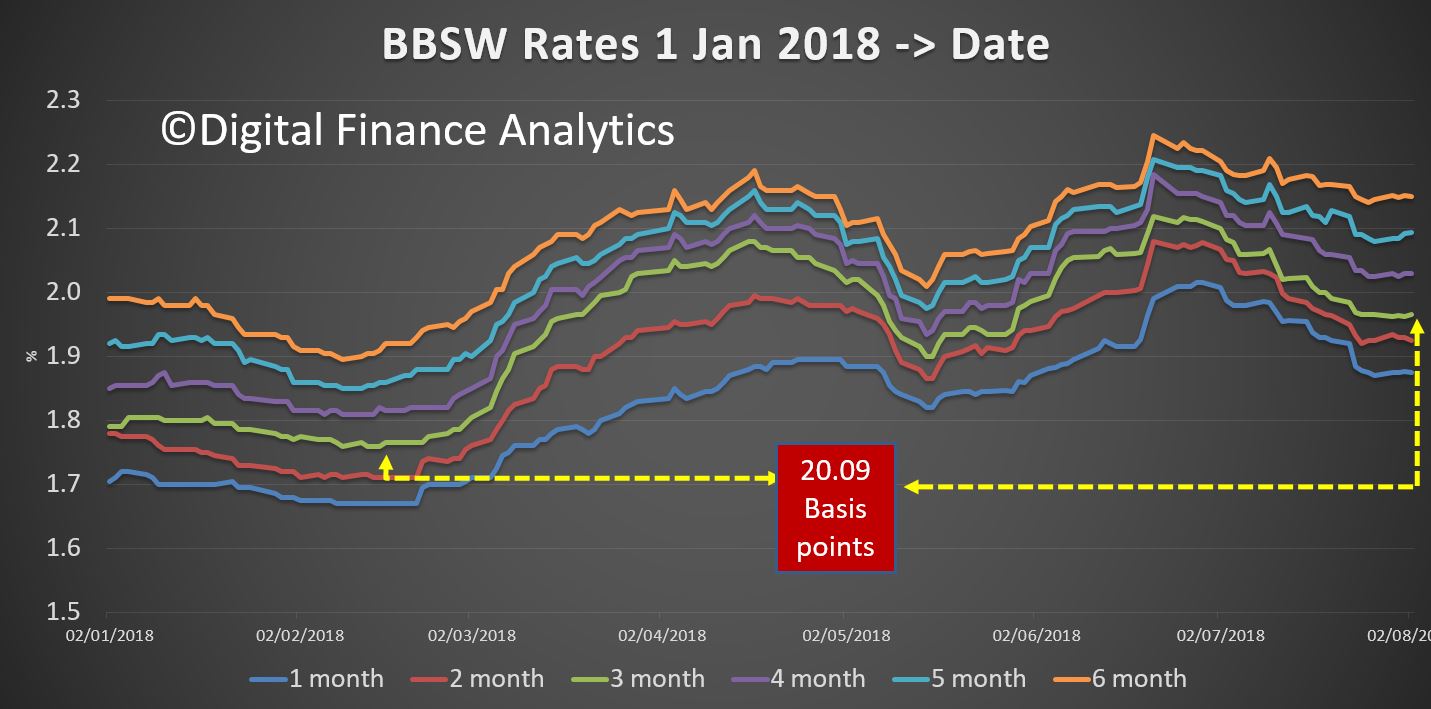

Recent easing interest rate pressures on the banks has decreased the need for them to lift rates higher by reference to the Bank Bill Swap Rates (BBSW), despite the fact that a number of smaller players have done so already.

Our analysis uses the DFA core market model which combines information from our 52,000 household surveys, public data from the RBA, ABS and APRA; and private data from lenders and aggregators. The data is current to end June 2018. We analyse household cash flow based on real incomes, outgoings and mortgage repayments, rather than using an arbitrary 30% of income.

Our analysis uses the DFA core market model which combines information from our 52,000 household surveys, public data from the RBA, ABS and APRA; and private data from lenders and aggregators. The data is current to end June 2018. We analyse household cash flow based on real incomes, outgoings and mortgage repayments, rather than using an arbitrary 30% of income.

Households are defined as “stressed” when net income (or cash flow) does not cover ongoing costs. They may or may not have access to other available assets, and some have paid ahead, but households in mild stress have little leeway in their cash flows, whereas those in severe stress are unable to meet repayments from current income. In both cases, households manage this deficit by cutting back on spending, putting more on credit cards and seeking to refinance, restructure or sell their home. Those in severe stress are more likely to be seeking hardship assistance and are often forced to sell.

Probability of default extends our mortgage stress analysis by overlaying economic indicators such as employment, future wage growth and cpi changes. Our Core Market Model also examines the potential of portfolio risk of loss in basis point and value terms. Losses are likely to be higher among more affluent households, contrary to the popular belief that affluent households are well protected.

The outlined data and analysis on mortgage stress does not occur in a vacuum. The revelations from the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Commission) have highlighted deep issues in the regulatory environment that have contributed to the household debt “stress bomb”. However, most of the media commentary on the regulatory framework has been superficial or poorly informed. For example, several commentators have strongly criticised the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) for not doing enough but have failed to explain what ASIC has in fact done, and what it ought to have done.

The outlined data and analysis on mortgage stress does not occur in a vacuum. The revelations from the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Commission) have highlighted deep issues in the regulatory environment that have contributed to the household debt “stress bomb”. However, most of the media commentary on the regulatory framework has been superficial or poorly informed. For example, several commentators have strongly criticised the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) for not doing enough but have failed to explain what ASIC has in fact done, and what it ought to have done.

The Commission has highlighted major concerns regarding the law and practice of responsible lending. North has published widely on responsible lending law, standards and practices over the last 3-4 years, and continues to do so. Her latest work (which is co-authored with Therese Wilson from Griffith University) outlines and critiques the responsible lending actions taken ASIC from the beginning of 2014 until the end of June 2017. This paper was published by the Federal Law Review, a top ranked law journal, this month. A draft version of the paper can be downloaded at https://ssrn.com/author=905894.

The responsible lending study by North and Wilson found that ASIC proactively engaged with lenders, encouraged tighter lending standards, and sought or imposed severe penalties for egregious conduct. Further, ASIC strategically targeted credit products commonly acknowledged as the riskiest or most material from a borrower’s perspective, such as small amount credit contracts (commonly referred to as payday loans), interest only home loans, and car loans. North suggests “ASIC deserves commendation for these efforts but could (and should) have done more given the very high levels of household debt. The area of lending of most concern, and that ASIC should have targeted more robustly and systematically, is home mortgages (including investment and owner occupier loans).”

Reported concerns regarding actions taken by the other major regulator of the finance sector, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), have been muted so far. However, an upcoming paper by North and Wilson suggests APRA (rather than ASIC) should be the primary focus of regulatory criticism. This paper concludes that “APRA failed to reasonably prevent or constrain the accumulation of major systemic risks across the financial system and its regulatory approach was light touch at best.”

Stress by The Numbers.

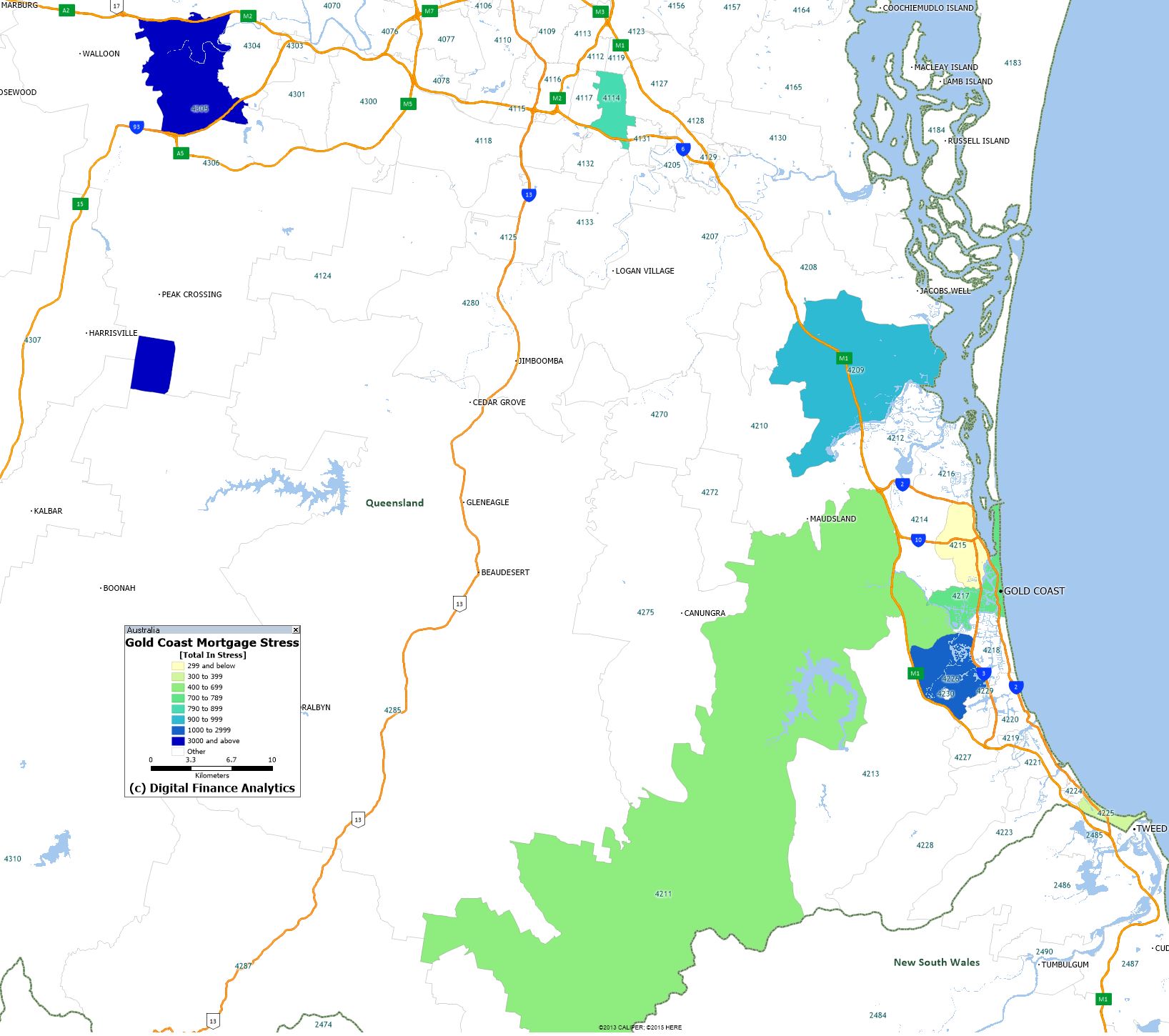

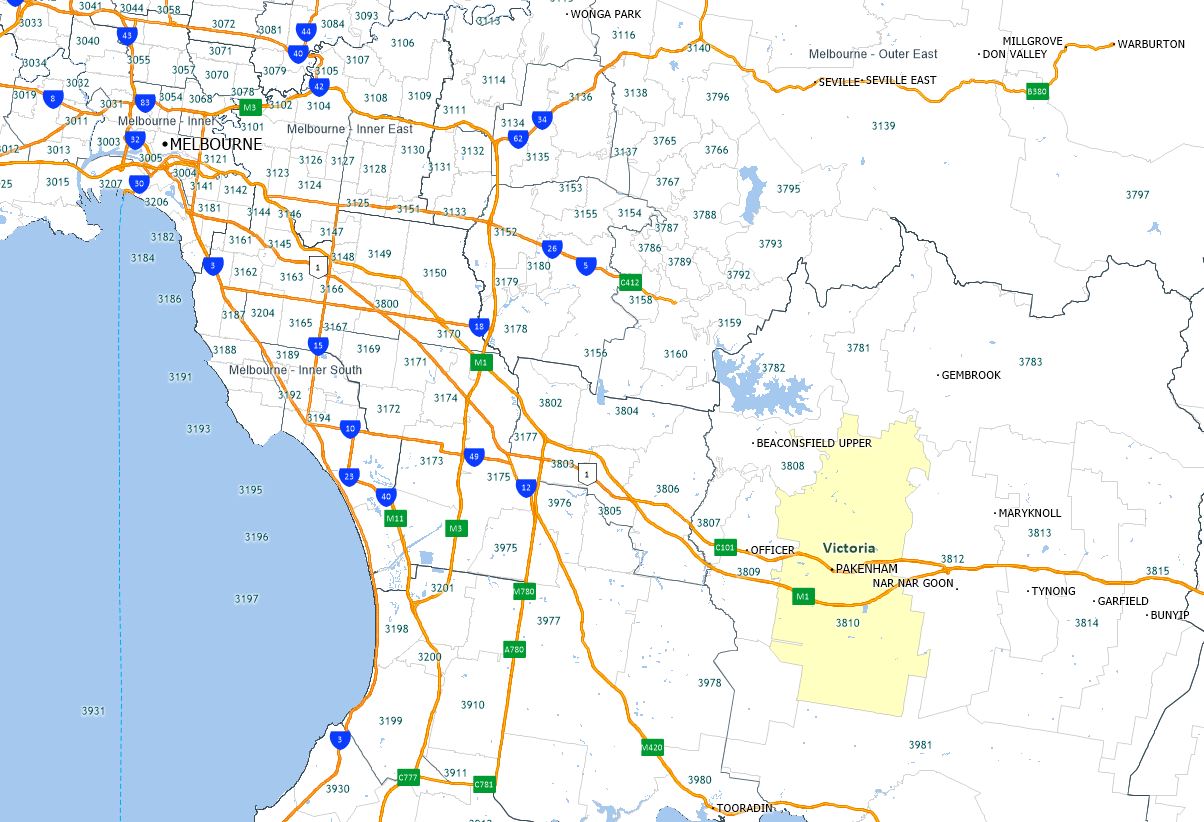

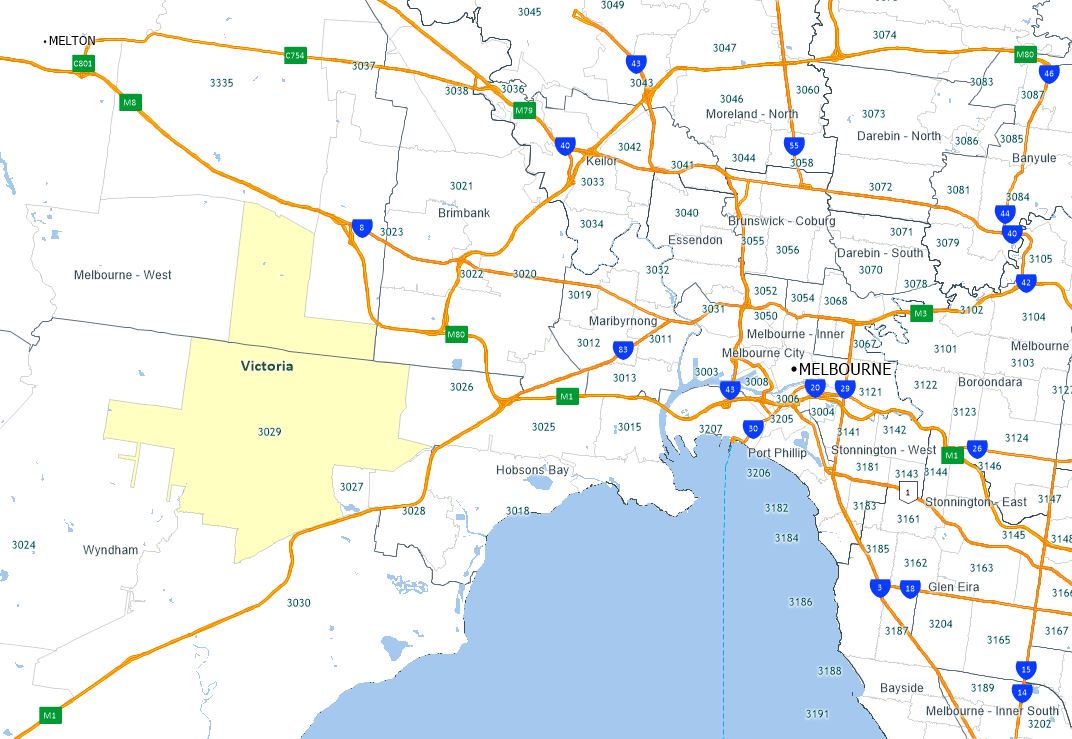

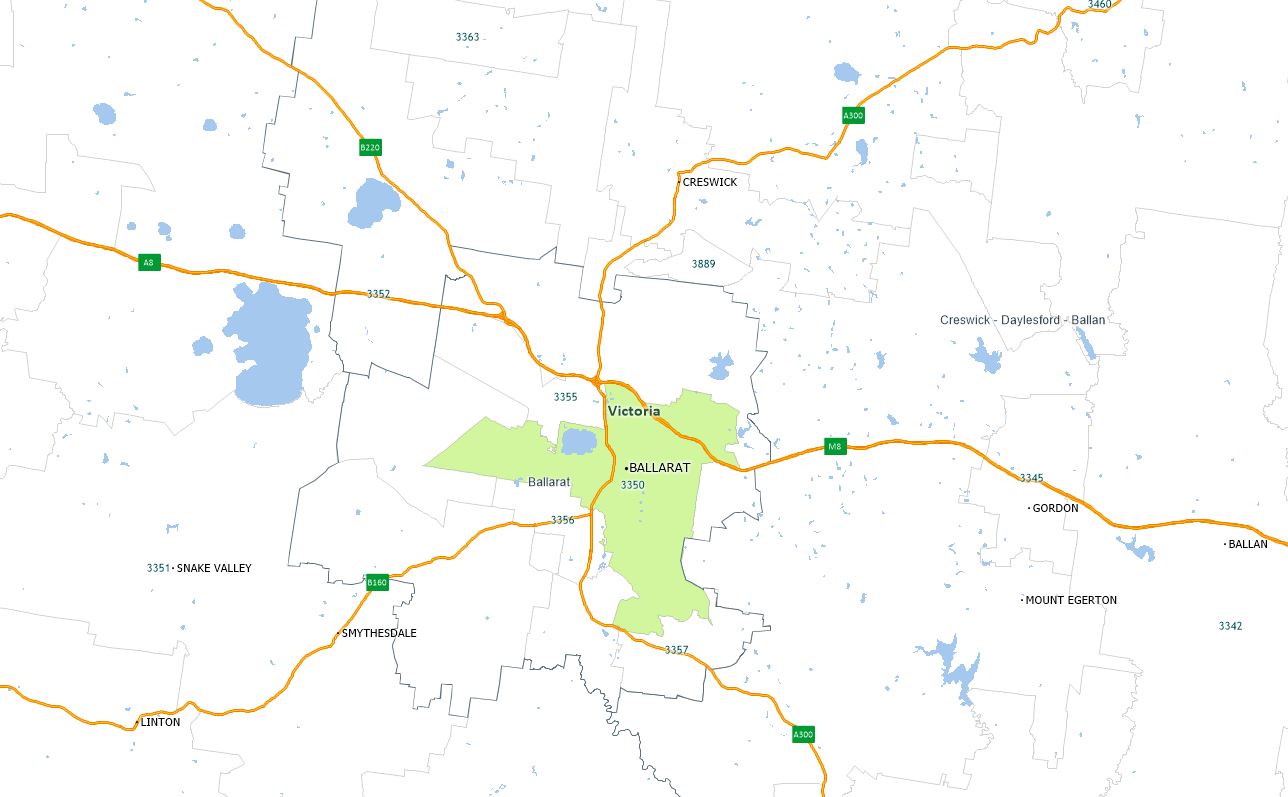

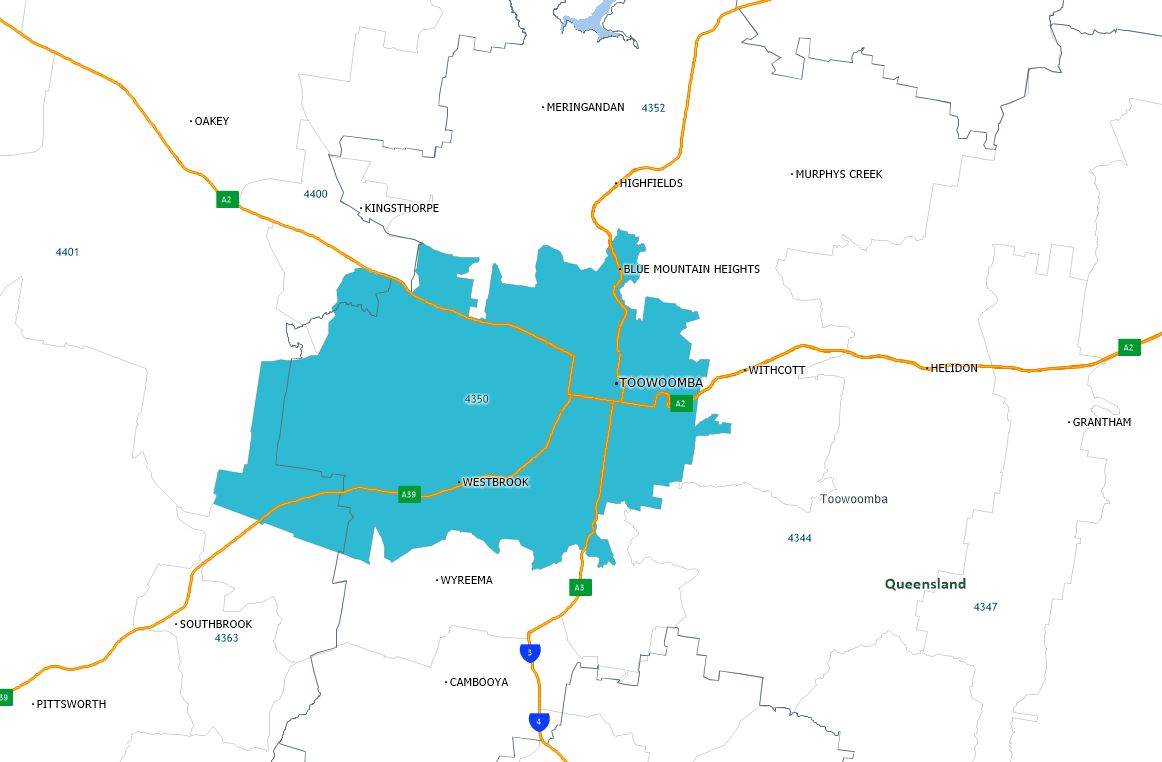

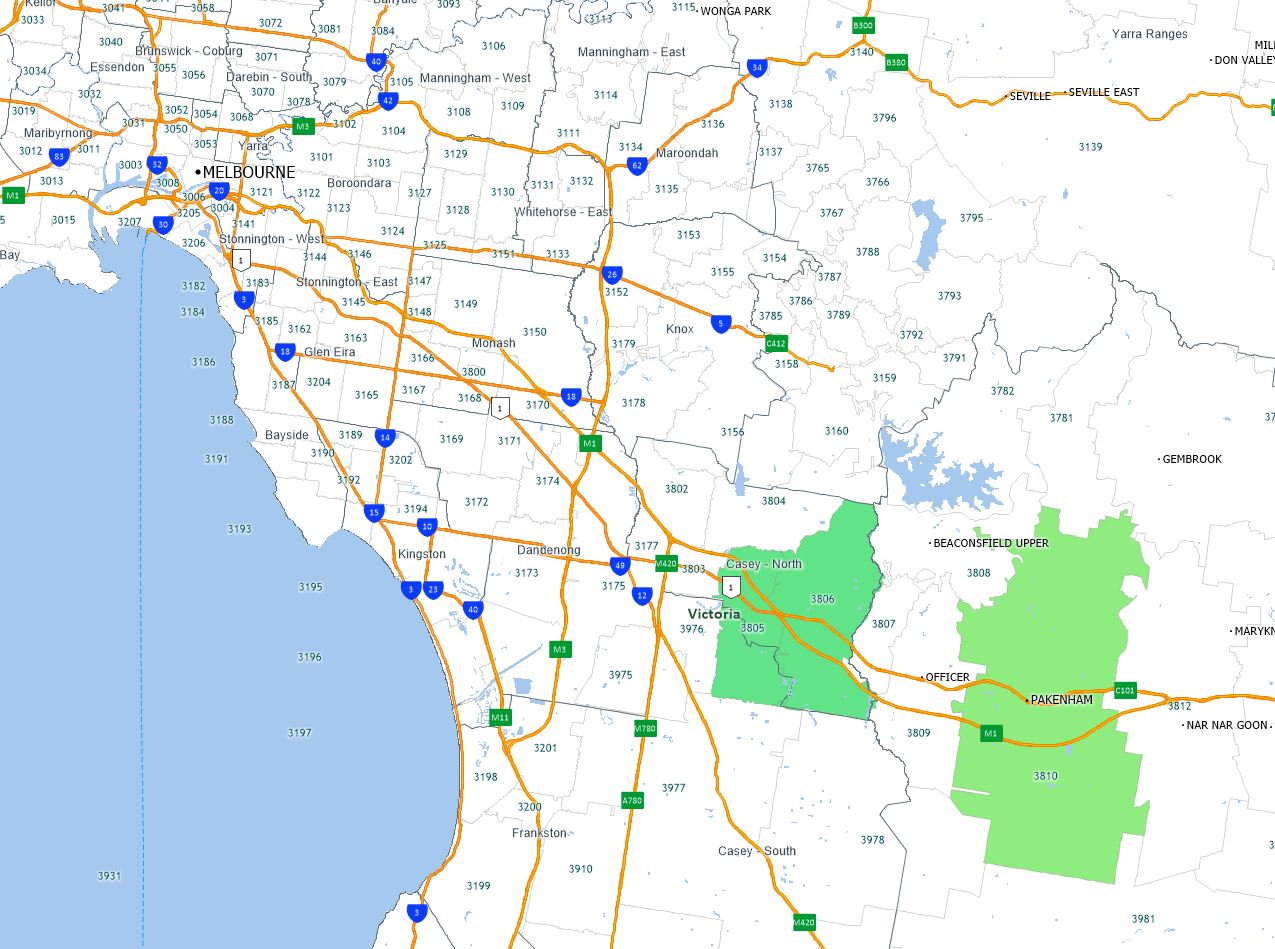

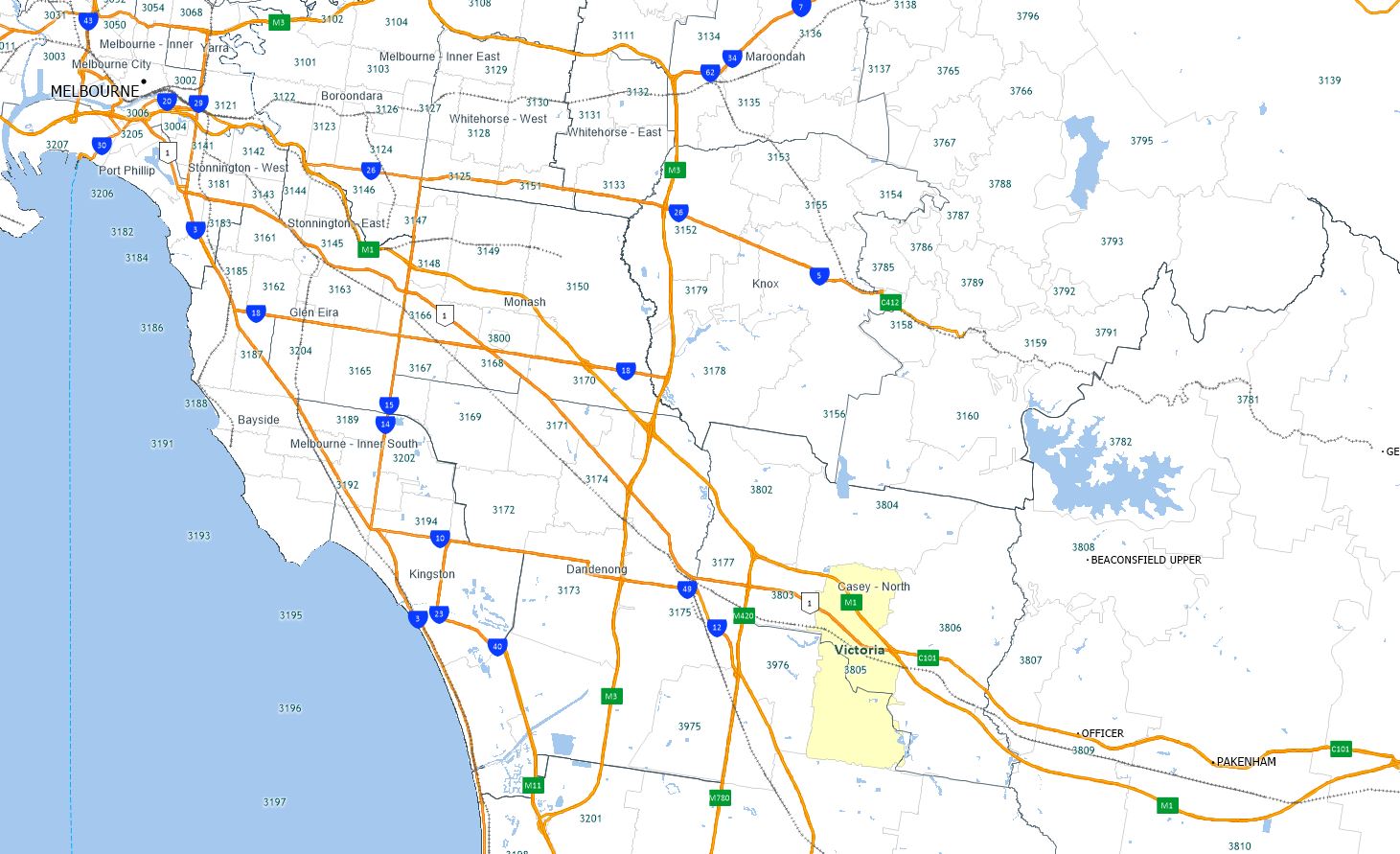

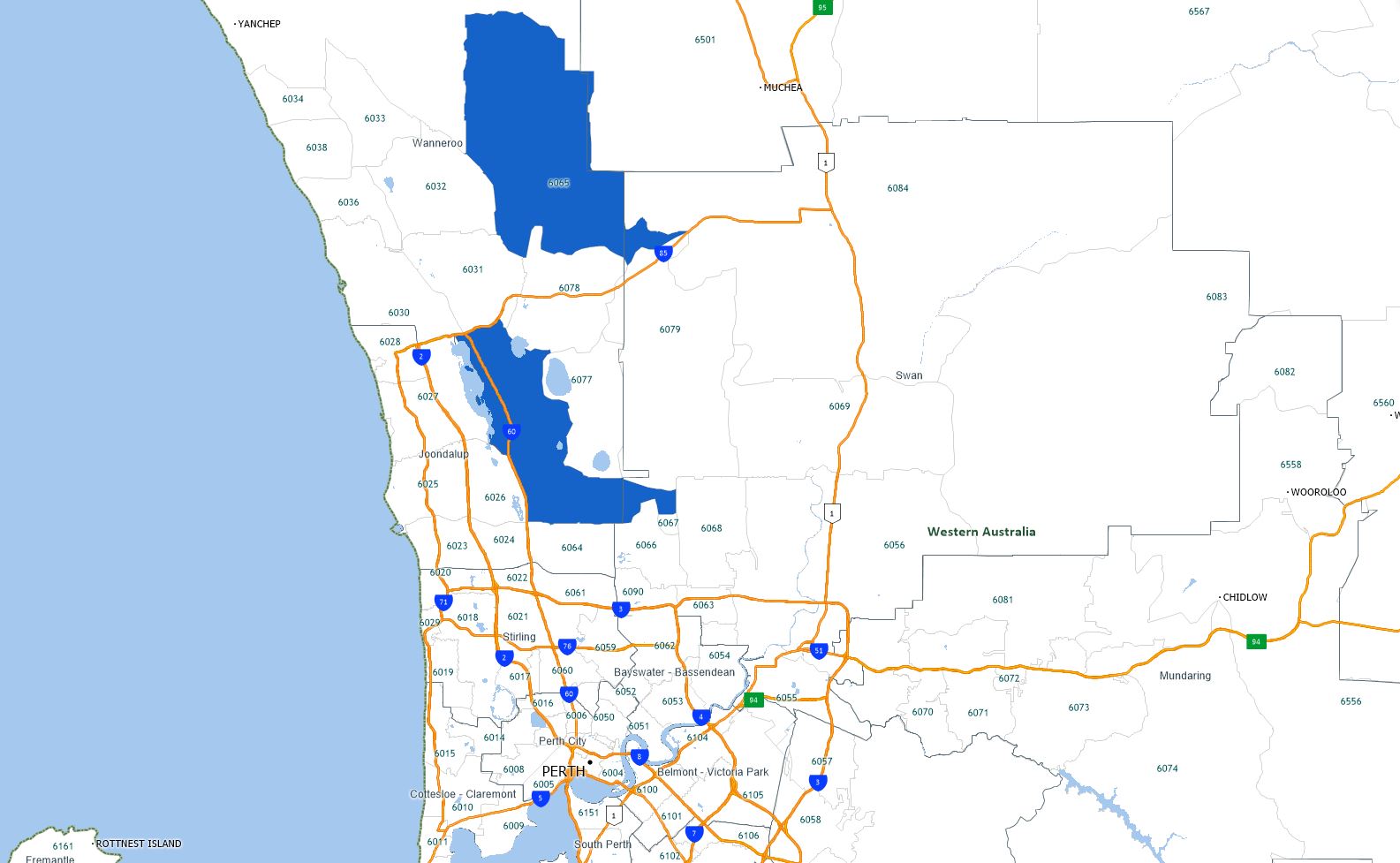

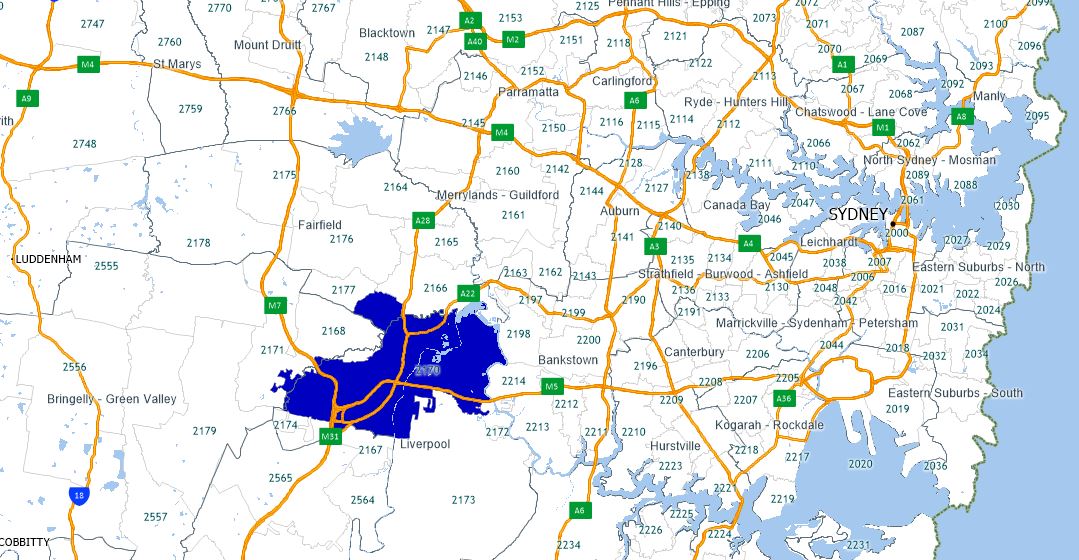

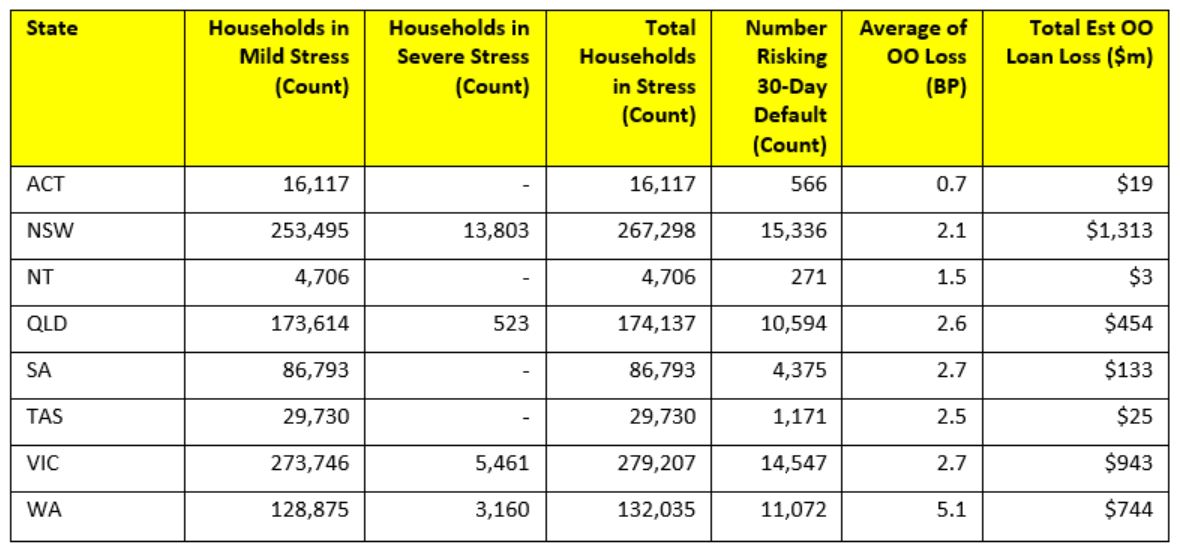

Regional analysis shows that NSW has 267,298 households in stress (264,737 last month), VIC 279,207 (266,958 last month), QLD 174,137 (172,088 last month) and WA has 132,035 (129,741 last month). The probability of default over the next 12 months rose, with around 11,000 in WA, around 10,500 in QLD, 14,500 in VIC and 15,300 in NSW.

The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.3 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($943 million) from Owner Occupied Borrowers, which equates to 2.10 and 2.7 basis points respectively. Losses are likely to be highest in WA at 5.1 basis points, which equates to $744 million from Owner Occupied borrowers.

The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.3 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($943 million) from Owner Occupied Borrowers, which equates to 2.10 and 2.7 basis points respectively. Losses are likely to be highest in WA at 5.1 basis points, which equates to $744 million from Owner Occupied borrowers.

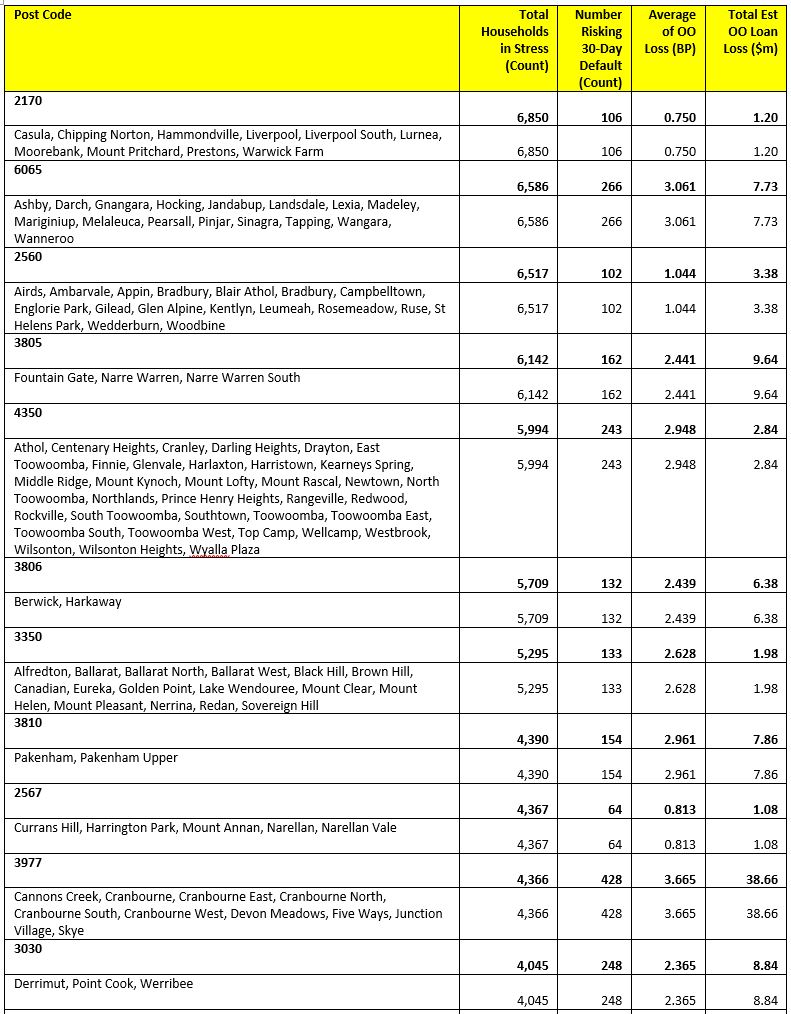

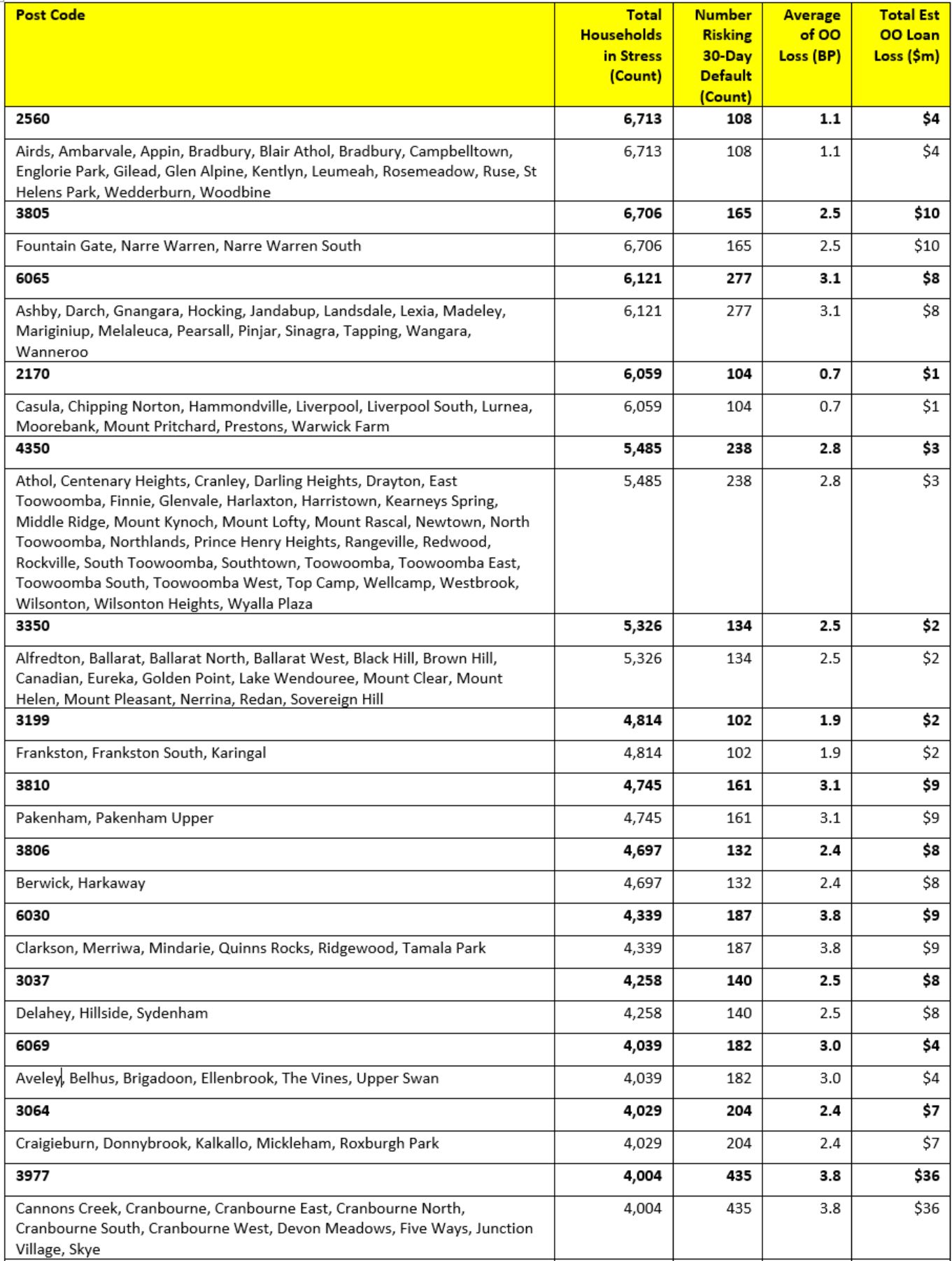

Top Post Codes By Stressed Households

[1] RBA E2 Household Finances – Selected Ratios March 2018

[1] RBA E2 Household Finances – Selected Ratios March 2018

You can request our media release. Note this will NOT automatically send you our research updates, for that register here.

[contact-form to=’mnorth@digitalfinanceanalytics.com’ subject=’Request The July 2018 Stress Release’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email Me The July 2018 Media Release’ type=’radio’ required=’1′ options=’Yes Please’/][contact-field label=”Comment If You Like” type=”textarea”/][/contact-form]

Note that the detailed results from our surveys and analysis are made available to our paying clients.