Today we examine the Mortgage Industry Omnishambles. And it’s more than just a flesh wound!

Welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly to 17th March 2018. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

Welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly to 17th March 2018. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

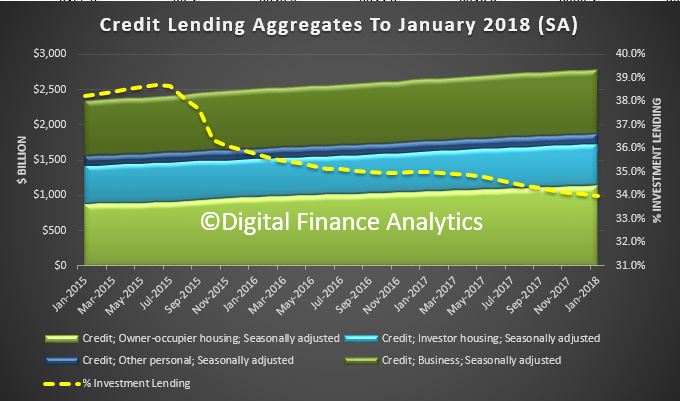

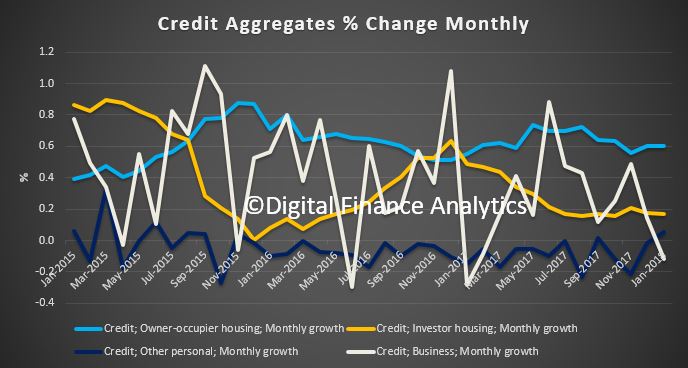

In this week’s review of property and finance news we start with the latest January data from the ABS which shows lending for secured housing rose 0.14% or 28.8 million to $21.1 billion. Secured alterations fell 1%, down $3.9 million to $391 million. Fixed personal loans fell 0.1%, down $1.2 million to $4.0 billion, while revolving loans fell 0.06%, down $1.3 million to $2.2 billion.

Investment lending for construction of dwellings for rent rose 0.86% or $10 million to $1.2 billion. Investment lending for purchase by individuals fell 1.34%, down $127.7 million to $9.4 billion, while investment lending by others rose 7.7% up $87.2 million to $1.2 billion.

Fixed commercial lending, other than for property investment rose 1.25% of $260.5 million to $21.1 billion, while revolving commercial lending rose 2.5% or $250 million to $10.2 billion.

The proportion of lending for commercial purposes, other than for investment housing was 45% of all commercial lending, up from 44.5% last month.

The proportion of lending for property investment purposes of all lending fell 0.1% to 16.6%.

So, we are seeing a rotation, if a small one, towards commercial lending for more productive purposes. However, lending for property and for investment purposes remains quite strong. No reason to reduce lending underwriting standards at this stage or weaken other controls.

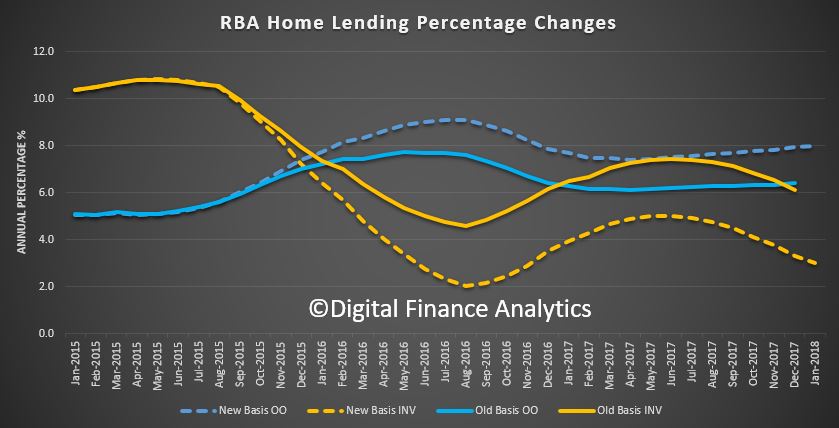

But this also explains the deep rate cuts the banks are now offering – even to investors – ANZ Bank and the National Australia Bank were the last of the big four to announce cuts to their fixed rates, following similar announcements from the Commonwealth Bank and Westpac. NAB has dropped its five-year fixed rate for owner-occupied, principal and interest home loans by 50 basis points, from 4.59 per cent to 4.09 per cent. The bank has also reduced its fixed rates on investor loans by up to 35 basis points, with rates starting from 4.09 per cent. And last week ANZ also dropped fixed rates on its “interest in advance”, interest-only home loans by up to 40 basis points, with rates starting from 4.11 per cent. Further, fixed rates on its owner-occupied, principal and interest home loans have fallen by 10 basis points, with rates now starting from 3.99 per cent. This fixed rate war shows our big banks are not pricing in a rate hike anytime soon.

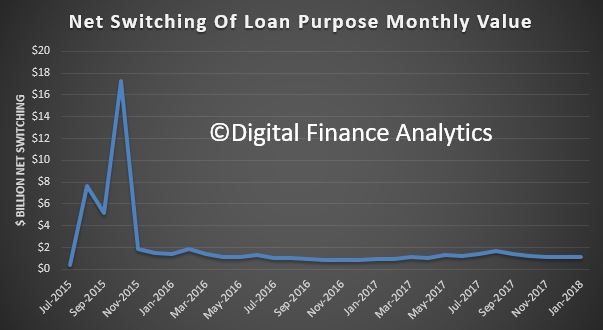

But we think these offers will likely encourage churn among existing borrowers, rather than bring new buyers to the market. For example, the ABS housing finance data showed that in original terms, the number of first home buyer commitments as a percentage of total owner occupied housing finance commitments rose to 18.0% in January 2018 from 17.9% in December 2017 – and this got the headline from the real estate sector, but the absolute number of first time buyers fell, thanks mainly to falls of 22.3% in NSW and of 13.3% in VIC. More broadly, there were small rises in refinancing and investment loans for entities other than individuals.

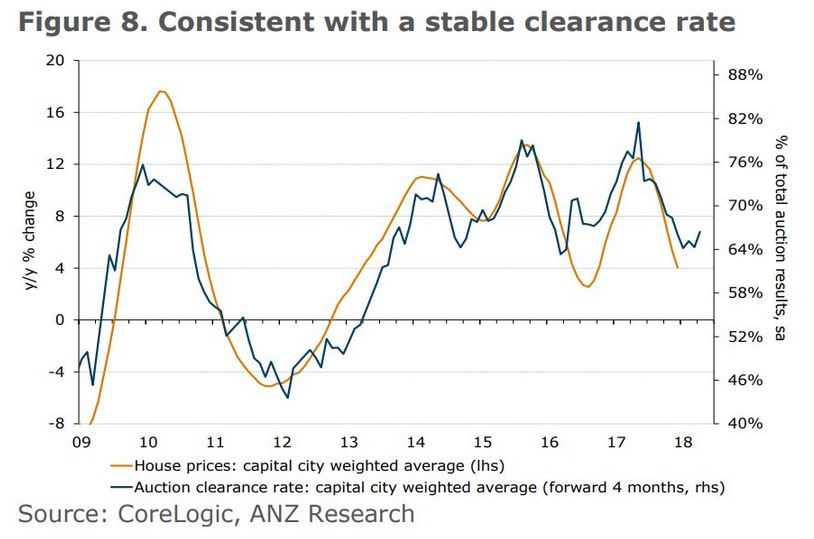

The latest data from CoreLogic shows home prices fell again this week, with Sydney down for the 27th consecutive week, and their index registering another 0.09% drop, whilst auction volumes were down on last week. They say that last week, the combined capital city final auction clearance rate fell to 63.3 per cent across a lower volume of auctions with 1,764 held, down from the 3,026 auctions over the week prior when a slightly higher 63.6 per cent cleared. The weighted average clearance rate has continued to track lower than results from last year; when over the corresponding week 75.1 per cent of the 1,473 auctions sold.

But the strategic issues this week relate to the findings from the Royal Commission and from the ACCC on mortgage pricing. I did a separate video on the key findings, but overall it was clear that there are significant procedural, ethical and even legal issue being raised by the Commission, despite their relatively narrow terms of reference. They cannot comment on bank regulation, or macroprudential, but the Inquiries approach is to examine a series of case studies, from the various submissions they have received, and then apply forensic analysis to dig into the root causes examining misconduct. The question of course is, do the specific examples speak to wider structural questions as we move from the specific instances. We discussed this on ABC Radio this week.

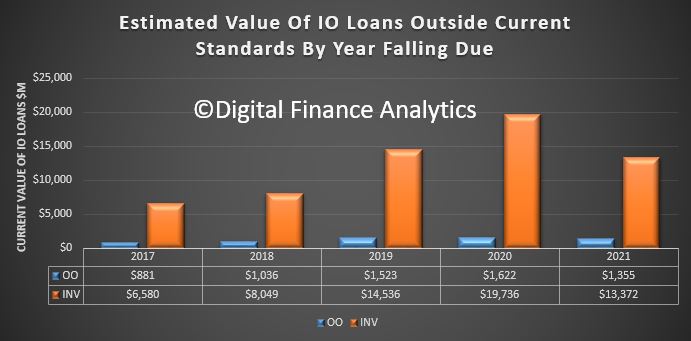

From NAB we heard about referrer’s providing leads to the Bank, outside normal lending practices and processes, and some receiving large commissions, despite not being in the ambit of the responsible lending code. From CBA we heard that the bank was aware of the conflict brokers have especially when recommending an interest only loan, because the trail commission will be higher as the principal amount is not repaid. And from Aussie, we heard about their reliance on lenders to trap fraud, as their own processes were not adequate. And we also heard of examples of individual borrowers receiving loans thanks to poor conduct, or even fraud. We also heard about how income and expenses are sometimes misrepresented. So, the question is, do these various practices show up more widely, and what does this say about liar loans, and mortgage systemic risk?

We always struggled to match the data from our independent household surveys with regards to loan to income, and loan to value, compare with loan portfolios we looked at from the banks. Now we know why. In some cases, income is over stated, expenses are understated, and so loan serviceability is a potentially more significant issue than the banks believe – especially if interest rates rise. In fact, we saw very similar behaviours to the finance industry in the USA before the GFC, suggesting again we may see the same outcomes here. One other point, every lender is now on notice that they need to look at their current processes and back book, to test affordability, serviceability and risk. This is a big deal.

I will also be interested to see if the Commission turns to look at foreclosure activity, because this is the other sleeper. Mortgage delinquency in Australia appears very low, but we suspect this is associated with heavy handed forced sales. Something again which was apparent around the GFC.

More specifically, as we said in a recent blog, the role and remuneration models for brokers are set for a significant shakedown.

Turning to the ACCC report on mortgage pricing, this was also damming. Back in June 2017, the banks indicated that rate increases were primarily due to APRA’s regulatory requirements, but now under further scrutiny they admitted that other factors contributed to the decision, including profitability. Last December, the ACCC was called on by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics to examine the banks’ decisions to increase rates for existing customers despite APRA’s speed limit only targeting new borrowers. The investigation falls under the ACCC’s present enquiry into residential mortgage products, which was established to monitor price decisions following the introduction of the bank levy. Here are the main points.

- Banks raised rates to reach internal performance targets: concern about a shortfall relative to performance targets was a key factor in the rate hikes which were applied across the board. Even small increases can have a significant impact on revenue, the report found. And the majority of existing borrowers would likely not be aware of small changes in rates and would therefore be unlikely to switch.

- A shared interest in avoiding disruption: Instead of trying to increase market share by offering the lowest interest rates, the big four banks were mainly preoccupied and concerned with each other when making pricing decisions. It shows a failure in competition (my words).

- Reputation is everything: The banks it seems were very conscious of how they should explain changes. As it happens, blaming the regulators provides a nice alibi/

- For Profit: Internal memos also spoke of the margin enhancement equating to millions of dollars which flowed from lifting investment loans.

- New Loans are cheaper, legacy rates are not. Banks of course are offering deep discounts to attract new customers, funded by the back book repricing. The same, by the way, is true for deposits too.

The Australian Bankers Association “silver lining” statement on the report said they welcomed the interim report into residential mortgages, which clearly shows very high levels of discounting in the Australian home loan market. It’s clear that competition is delivering better deals for customers, shopping around works and Australians should continue to do so to get the best discounts on the advertised rate. But they are really missing the point!

We will see if the final report changes, but if not these are damming, but not surprising, and again shows the pricing power the major lenders have.

So to the question of future rate rises. The FED meets this week, and the expectation is they will lift rates again, especially as the TRUMP tax cuts are inflationary, at a time when the US economy is already firing. In a recent report Fitch Ratings said that Central banks are becoming less cautious about normalising monetary policy in the face of strong growth and diminishing spare capacity. They expect the Fed to raise rates no less than seven times before the end of next year. And while still sounding tentative, the European Central Bank is clearly laying firm groundwork for phasing out QE completely later this year. They now also expect the Bank of England to raise rates by 25bp this year.

Guy Debelle, RBA Deputy Governor spoke on “Risk and Return in a Low Rate Environment“. He explored the consequences of low rates, on asset prices, and asks what happens when rates rise. He suggested that we need to be alert for the effect the rise in the interest rate structure has on financial market functioning, and that investors were potentially too complacent. There are large institutional positions that are predicated on a continuation of the low volatility regime remaining in place. He had expected that volatility would move higher structurally in the past and this has turned out to be wrong. But He thinks there is a higher probability of being proven correct this time. In other words, rising rates will reduce asset prices, and the question is – have investors and other holders of assets – including property – been lulled into a false sense of security?

All the indicators are that rates will rise – you can watch our blog on this. Rising rates of course are bad news for households with large mortgages, exacerbated by the possibility of weaker ability to service loans thanks to fraud, and poor lending practice. We discussed this, especially in the context of interest only loans, and the problems of loan resets on the ABC’s 7:30 programme on Monday. We expect mortgage stress to continue to rise.

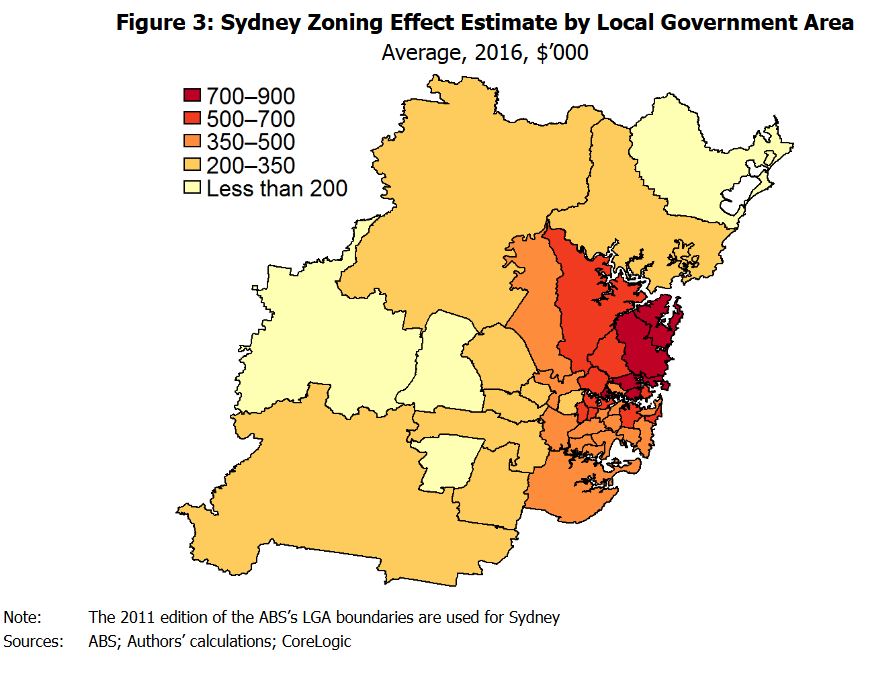

There was more discussion this week on Housing Affordability. The Conversation ran a piece showed that zoning is not the cause of poor affordability, and neither is supply of property. Indeed planning reform they say is not a housing affordability strategy. Australia needs a more realistic assessment of the housing problem. We can clearly generate significant dwelling approvals and dwellings in the right economic circumstances. Yet there is little evidence this new supply improves affordability for lower-income households. Three years after the peak of the WA housing boom, these households are no better off in terms of affordability. In part, this may reflect that fact that significant numbers of new homes appear not to house anyone at all. A recent CBA report estimated that 17% of dwellings built in the four years to 2016 remained unoccupied. If we are serious about delivering greater affordability for lower-income Australians, then policy needs to deliver housing supply directly to such households. This will include more affordable supply in the private rental sector, ideally through investment driven by large institutions such as super funds. And for those who cannot afford to rent in this sector, investment in the community housing sector is needed. In capital city markets, new housing built for sale to either home buyers or landlords is simply not going to deliver affordable housing options unless a portion is reserved for those on low or moderate incomes.

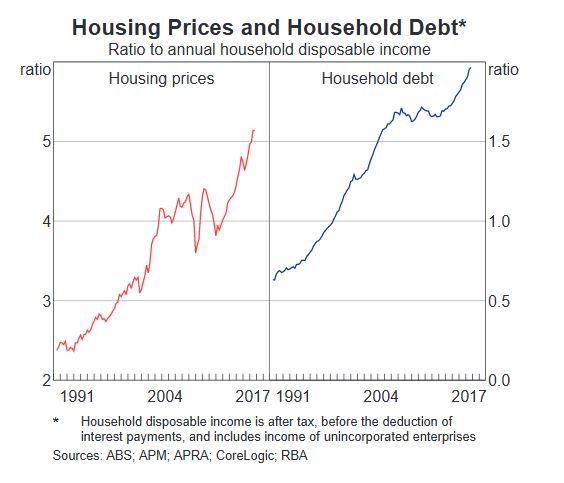

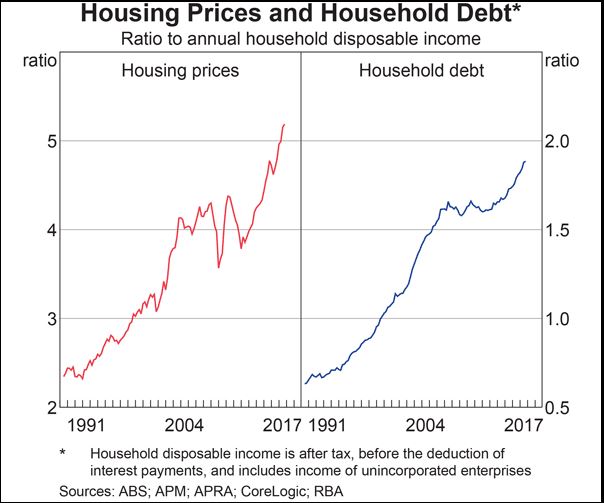

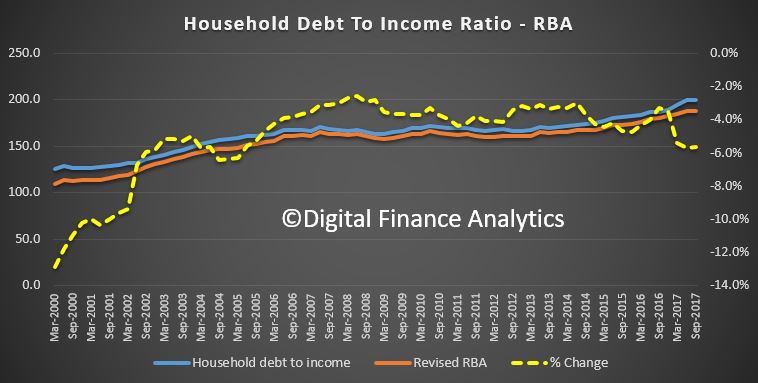

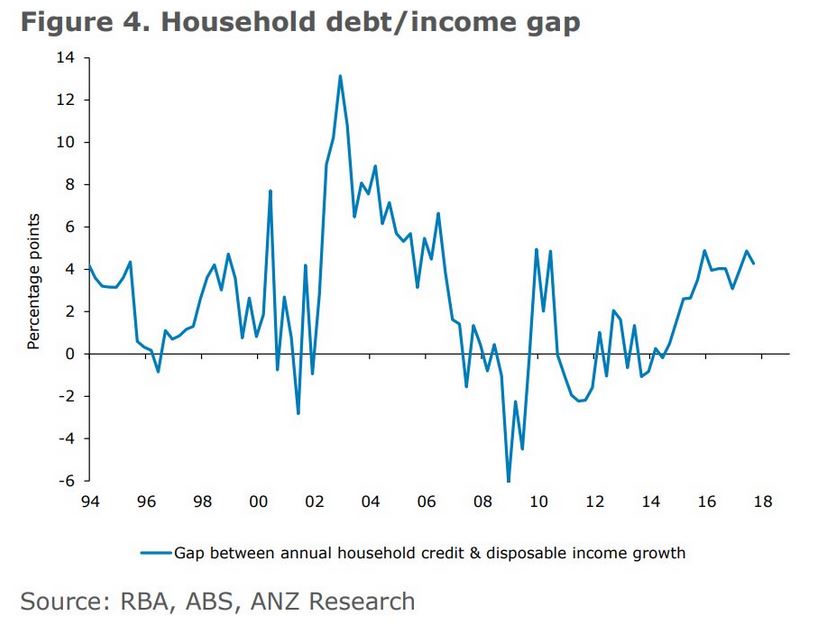

But they did not discuss the elephant in the room – booming credit. We discussed the relative strength of different drivers associated with home price rises in a separate, and well visited blog post, Popping The Housing Affordability Myth. But in summary, the truth is banks have pretty unlimited capacity to create more loans from thin air – FIAT – let it be. It is not linked to deposits, as claimed in classic economic theory. The only limit on the amount of credit is people’s ability to service the loans – eventually. With that in mind, we built a scenario model, based on our core market model, which allows us to test the relationship between home prices, and a series of drivers, including population, migration, planning restrictions, the cash rate, income, tax incentives and credit.

We found the greatest of these is credit policy, which has for years allowed banks to magic money from thin air, to lend to borrowers, to drive up home prices, to inflate the banks’ balance sheet, to lend more to drive prices higher – repeat ad nauseam! Totally unproductive, and in fact it sucks the air out of the real economy and money directly out of punters wages, but make bankers and their shareholders richer. One final point, the GDP calculation we use in Australia is flattered by housing growth (triggered by credit growth). The second driver of GDP growth is population growth. But in real terms neither of these are really creating true economic growth. To solve the property equation, and the economic future of the country, we have to address credit. But then again, I refer to the fact that most economists still think credit is unimportant in macroeconomic terms! The alternative is to continue to let credit grow well above wages, and lift the already heavy debt burden even higher. Current settings are doing just that, as more households have come to believe the only way is to borrow ever more. But, that is, ultimately unsustainable, and this why there will be an economic correction in Australia, and quite soon. At that point the poor mortgage underwriting chickens will come home to roost. And next time we will discuss in more detail how these scenarios are likely to play out. But already we know enough to show it will not end well.