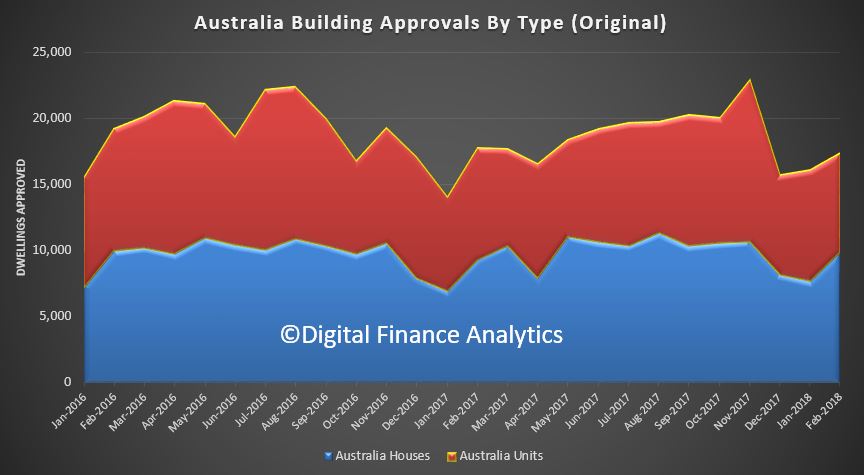

Australia has record levels of supply of new properties but despite various government interventions, housing still remains unaffordable for many.

Our study found the government could use more direct methods to deliver homes for people on low and moderate incomes, while leveraging the market. These methods, widespread across the United Kingdom and in major cities of the United States, are known as “inclusionary planning”.

This includes requiring developers to make a financial contribution towards affordable housing, or to dedicate completed dwellings, as part of the development approval process.

We studied the outcomes of inclusionary planning programs in parts of the United States and the United Kingdom, and more recent approaches in South Australia and New South Wales.

What techniques can ensure affordable housing in the mix

“Inclusionary zoning”, a common type of inclusionary planning, was first developed in the United States to counteract land use rules which excluded the lower end of the property market. For example, where rules would only permit large homes on single allotments.

Some states in the US have also adopted “anti-snob” laws. Under these laws, developers whose schemes include affordable housing can bypass local zoning controls, if an area has insufficient affordable housing for those on low and moderate incomes.

More recently, inclusionary planning programs are being used in many US cities in a bid to ensure that transport and infrastructure investment does not price out or displace lower income renters.

There are now more than 500 inclusionary planning schemes operating in municipalities across the US. Some require developers to include affordable housing as part of development in a particular zone (usually a fixed percentage of units or floor space).

For example inclusionary planning programs in the city of San Francisco, California (population of around 830,000) generate around 150–250 affordable units per year (around 12% of the city’s total supply).

Other schemes allow variations to planning rules in return for affordable housing. These variations might permit additional density in certain areas or waive certain requirements that would normally apply or expedite the development assessment process.

Other schemes require financial contributions from developers to offset the impact of a project on affordable housing demand or supply.

These programs provide a way for governments to ensure affordable housing for lower income residents even in rapidly gentrifying neighbourhoods.

How this plays out in England and Scotland

In England and Scotland, the supply of affordable housing is negotiated through the planning process. The general expectation is that 20 to 40% of new housing developments will be affordable. But proportions of affordable housing are allowed to vary on a case by case basis in light of the housing market and the costs of undertaking the development.

The main methods for this in England are section 106 agreements. These agreements, which come under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, specify the amount and type of affordable housing to be provided as part of a development.

Section 106 agreements have steadily gained traction since the 1990s. Between 2005–16, 83,790 affordable dwellings were secured through these agreements in England. This included 9,640 new dwellings in 2015–16.

Section 106 agreements have resulted in different types of affordable housing, including social housing, discounted home ownership, share equity schemes and affordable rental housing (offered at 20% less rent than for comparable properties in the same local housing market).

Our study found that when inclusionary planning model requirements are predictable and applied in a consistent way, developers accept them because they can factor costs into the price paid for land.

We also found most models work in conjunction with other government funding or subsidies, extending the value of this funding by reducing the cost of land for social or affordable housing.

What usually happens in Australia

Only the South Australia and New South Wales governments have similar types of planning schemes in Australia, although there are signs that other states may follow.

The SA government’s inclusionary planning target, announced in 2005, aims for 15% of significant new housing developments to be affordable.

By 2016 more than 2,000 affordable homes had been built and a further 3,476 homes committed. This amounts to about 17% of new housing supply in South Australia.

In NSW, inclusionary planning schemes only deliver affordable rental housing.

In the mid 1990s an inclusionary zoning scheme pilot was introduced to Pyrmont and Ultimo. This scheme was then extended to Green Square.

These schemes require that developers dedicate 0.8 to 3% of the floor area of developments for affordable housing, or that a monetary contribution be made in lieu of direct affordable housing provision.

However, to date, the NSW state government and many in the development sector have favoured voluntary mechanisms (such as density bonuses for providing affordable housing) over mandatory ones to supply affordable rental housing.

For our study, we estimated the volume of affordable housing delivered through voluntary planning agreements and state policy giving a density bonus for affordable housing inclusion by examining individual development approval records.

We found that voluntary measures have so far delivered about 1,300 dwellings or between 0.5 to 1% of Sydney’s housing supply between 2009 and 2017.

How viable is inclusionary planning?

We found that voluntary planning incentives can encourage affordable housing, but as part of incremental residential development, within the existing planning framework.

However, affordable housing should be mandated when land is rezoned for residential development, when planning rules are varied for particular projects, or following major infrastructure investment.

Inclusionary planning can’t replace government funding in providing housing for those on the lowest incomes. However, inclusionary planning schemes can reduce land costs and ensure that affordable homes are well located near jobs and services.

Authors: Nicole Gurran, Professor of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Sydney; Catherine Gilbert, Research Assistant and PhD Candidate, Urban Housing Lab, University of Sydney

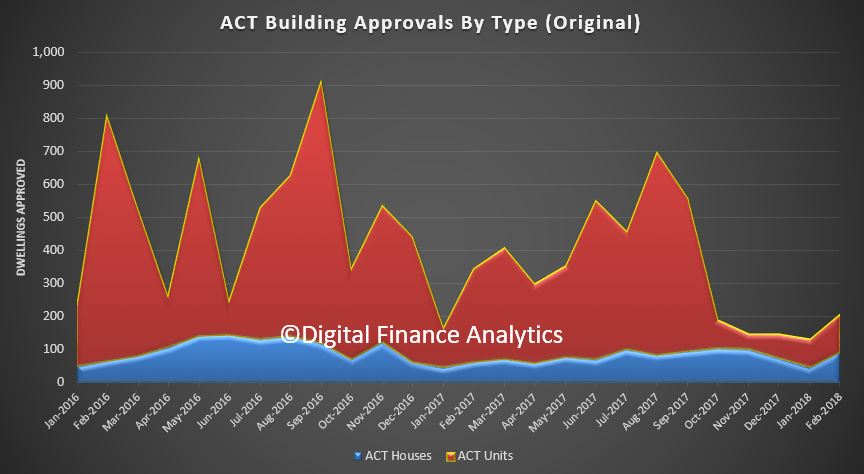

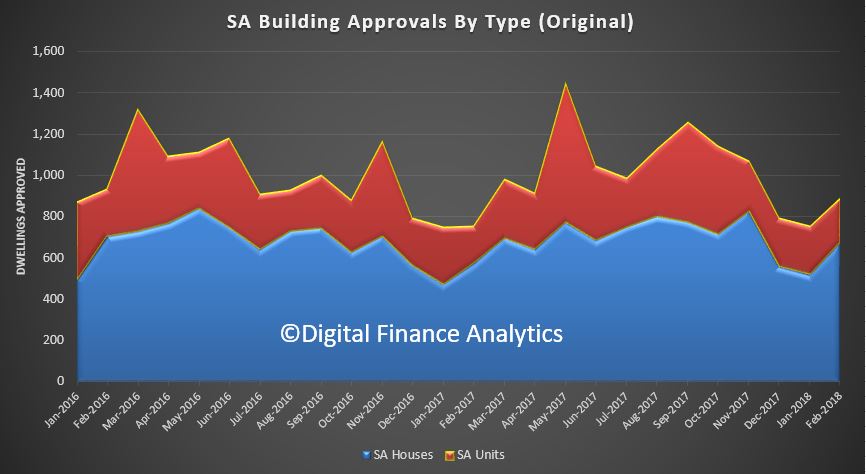

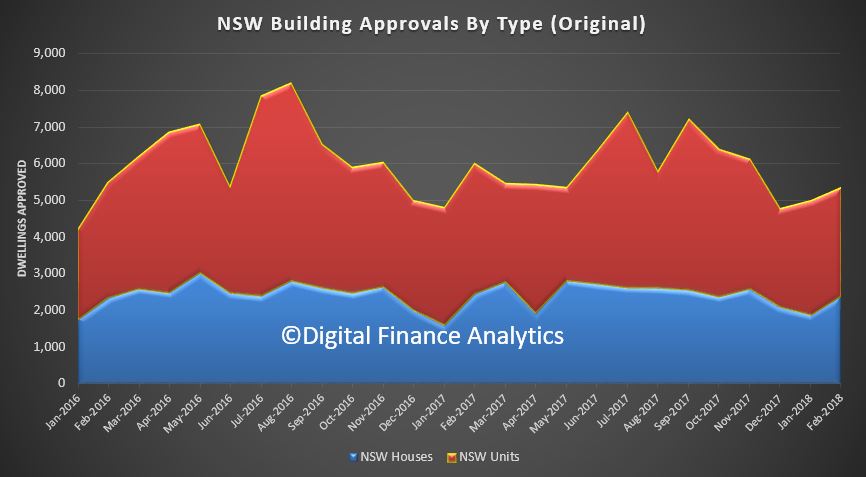

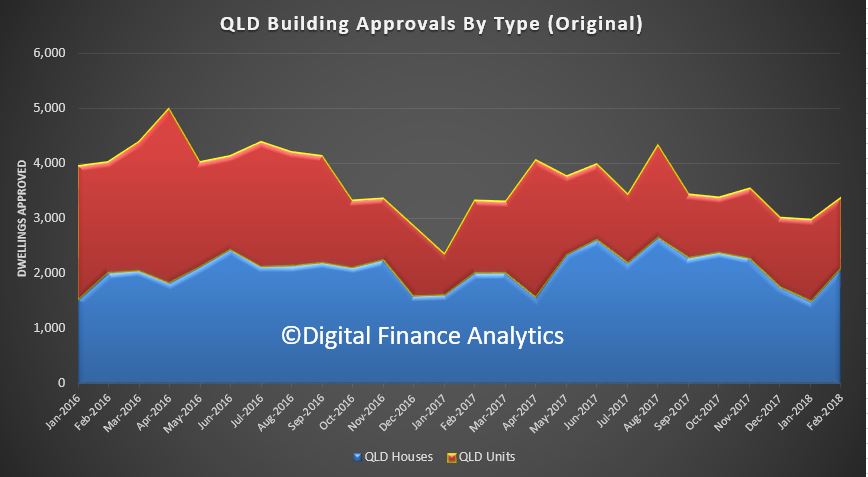

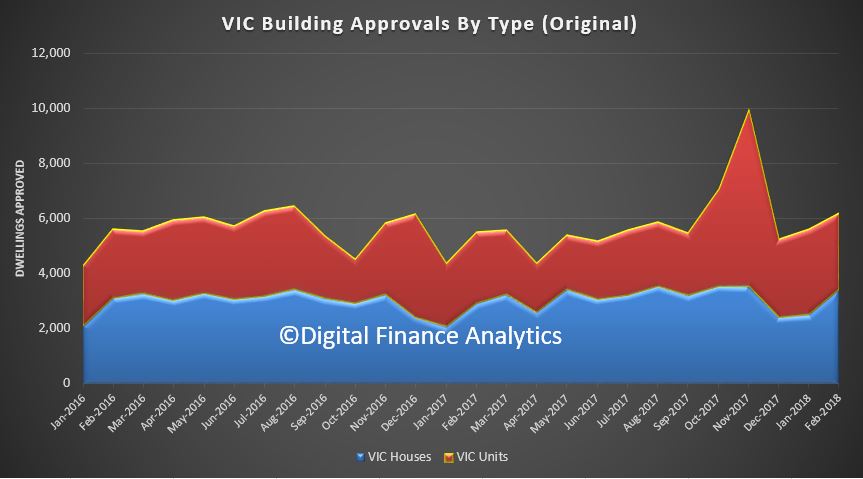

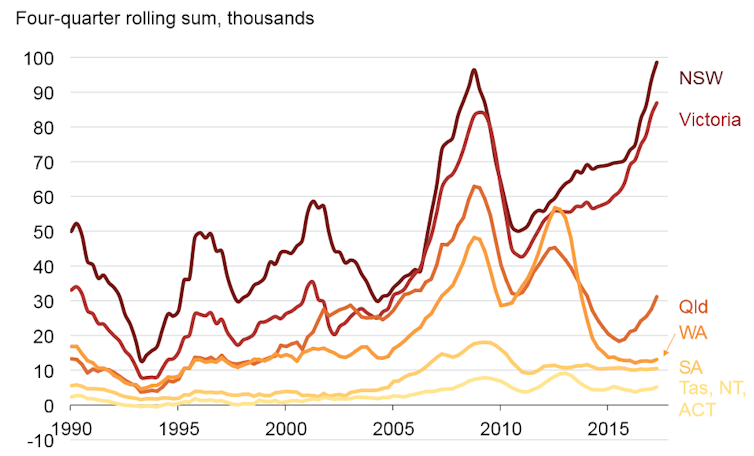

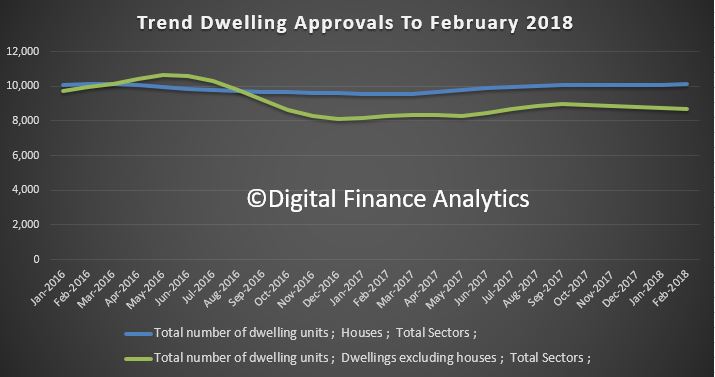

We can then look across the individual states, as there are significant variations. Among the states and territories, the biggest trend decrease in dwelling approvals in February was the Australian Capital Territory down 18.7 per cent,

We can then look across the individual states, as there are significant variations. Among the states and territories, the biggest trend decrease in dwelling approvals in February was the Australian Capital Territory down 18.7 per cent,