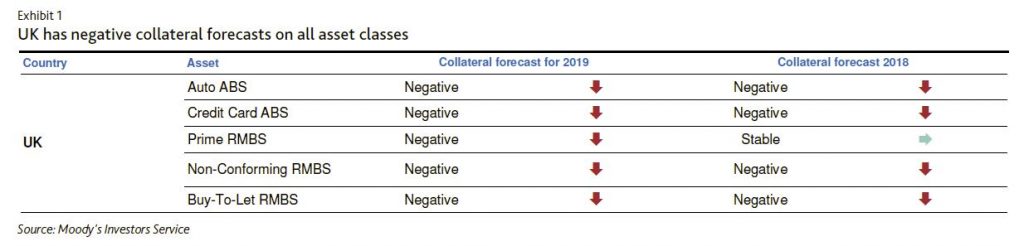

According to Moody’s on 15 January, UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) chief Executive Andrew Bailey, reiterated the organisation’s intention to improve so-called mortgage prisoners’ access to refinancing by relaxing current mortgage affordability regulations that preclude them refinancing into cheaper mortgage deals because they fail to meet affordability standards that were tightened in 2016.

Relaxing the mortgage affordability parameters for refinancing such borrowers’ mortgages would be credit positive for more than 60 UK RMBS securitisations containing pre-crisis assets, which equate to more than £29.0 billion of outstanding bonds.

The FCA has suggested that authorised UK lenders would be willing to refinance such mortgage prisoners if the borrower qualified for refinancing under the new rules, which would require the new mortgage installments to be lower than previous installments and for the borrower to be up to date with their payments. The new rules would replace current affordability tests for these borrowers, which make sure a borrower has enough money left to pay their mortgage installments in a stressed interest rate environment after covering all other basic needs (e.g. bills, food, childcare).

At present, a borrower refinancing with its current lender does not always require affordability re-testing, but some lenders, such as Southern Pacific Mortgage Limited and Bradford & Bingley plc, have stopped originating loans in recent years. Furthermore, a significant number of mortgage loans were sold to entities that are not authorised lenders, such as private equity firms or investment banks. In both cases, those affected borrowers can only refinance with new lenders, thus falling under the stricter affordability testing introduced post- crisis. FCA estimates that there are about 140,000 affected borrowers, 120,000 whose loans are owned by firms not authorised to lend and 20,000 borrowers whose lenders are inactive.

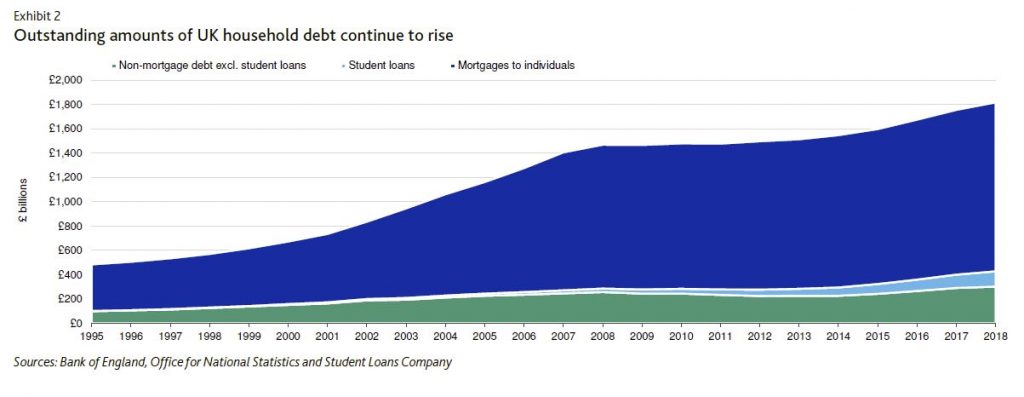

Moody’s expect performance to improve for securitisations containing legacy assets if the changes are enacted. The majority of mortgage prisoners’ installments accrue interest at relatively high floating rates. Therefore, their mortgage installments will increase in the event of an increased base rate, as is currently expected in the UK. Higher rates make affordability more challenging and have the potential to cause additional defaults.

If those borrowers can refinance at a lower interest rate, the mortgage loans instead exit the securitisation pools early, leading to increased credit enhancement for remaining noteholders and reduced future losses.

The exemption will have the greatest positive effect for more recent securitisations of pre-crisis mortgage loans because the majority of recent securitisations of legacy assets have been cleaned of arrears loans.

Transactions that closed prior to 2009, while also benefiting from the early repayment of loans and increased credit enhancement, are typically smaller in size and also usually already contain a high proportion of loans in arrears. Hence the redemption of loans by mortgage prisoners will tend to concentrate the pools’ exposure to loans with borrowers having real affordability problems.