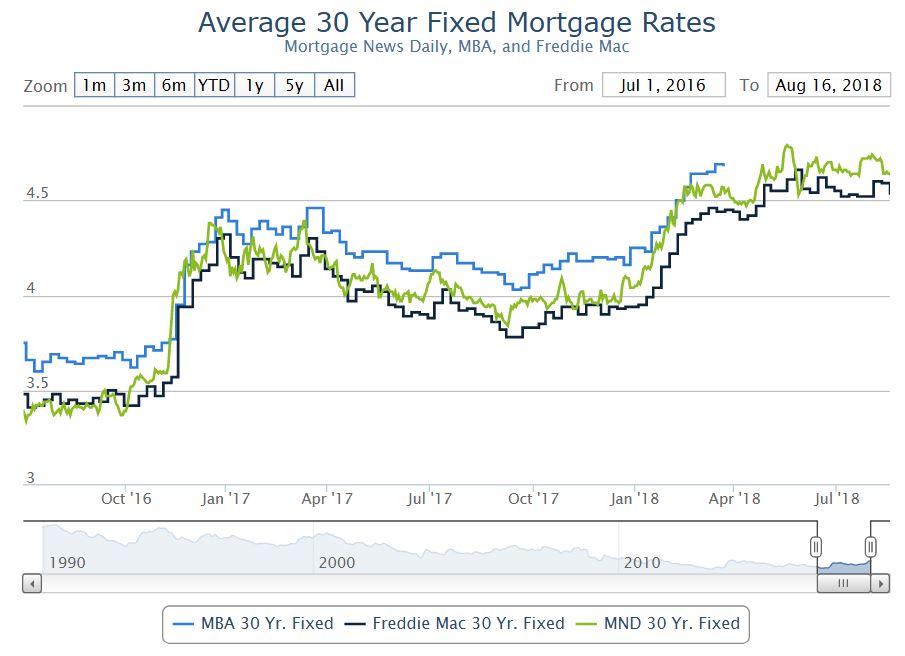

The U.S. business cycle has entered its boom phase. This is a period that typically comes closer to the end of the cycle, just prior to a recession. It is characterized by robust economic growth, tightening labor and product markets, intensifying wage and price pressures, monetary tightening, and higher interest rates.

Another feature of the boom phase of a business cycle is excessive risk-taking somewhere in the financial system. This fuels the boom and is eventually at the center of the subsequent bust. Subprime mortgage loans were the obvious culprit a decade ago, runaway internet stocks that pumped up a stock market bubble were the problem in the early-2000s recession, and the savings and loan crisis incited the early 1990s downturn.

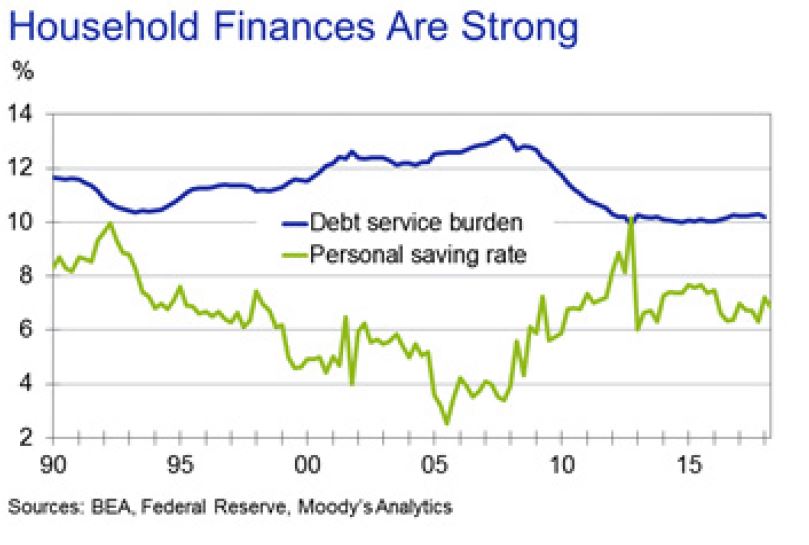

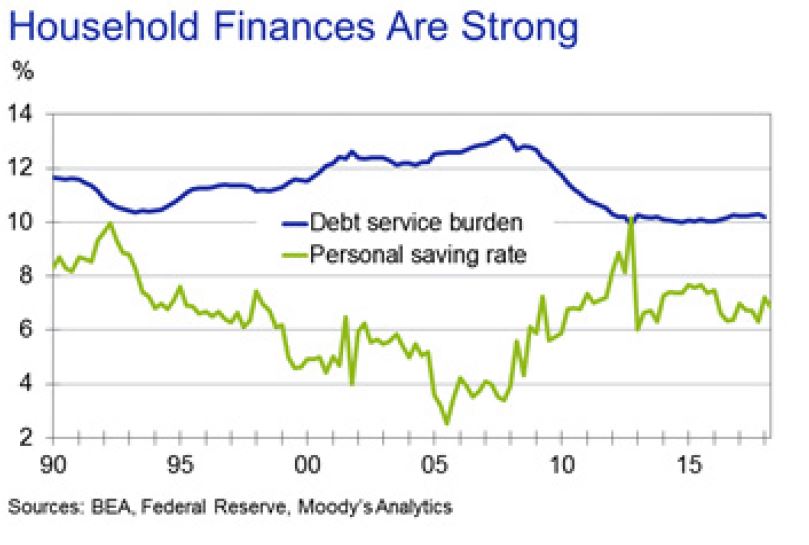

Risk-taking is clearly on the rise in this cycle, the aforementioned overvalued asset markets and easier underwriting are testimonial, but it is unclear precisely what might do this cycle in. There has been handwringing that households may be overborrowing again. But this concern seems overblown. Household credit growth is consistent with income gains, and debt loads that had fallen sharply after the last recession show no indication of rising. Debt service burdens remain low. And personal savings rates look ample after recent data revisions.

To be sure, vehicle and retail card lenders were extending too much credit not too long ago, and credit quality eroded. But lenders have since upped their standards, and delinquencies have peaked. Student loans are a problem, but not for the financial system, since the bulk of these loans are backed by the federal government. Student loans are thus a taxpayer problem, which could manifest itself in the next downturn by adding to the nation’s fiscal problems; policy makers will be under intense pressure to forgive and forbear on more of this debt.

Even so, worries that the nation’s ballooning budget deficits and debt load could do this cycle in are also overdone. They are a corrosive on growth as they push up long-term interest rates, but we are still a long way from U.S. Treasury bonds losing their safe-haven status to global investors. Municipal debt is more of an issue. But, while it will likely exacerbate the next recession, it won’t be the catalyst for it.

Leveraged lending

The most serious developing threat to the current cycle is lending to highly leveraged nonfinancial businesses. Across all businesses, borrowing appears manageable. The ratio of debt outstanding to GDP is about as high as it has ever been, yet this is a continuation of a long-running trend and reflects a broadening in the availability of credit to more businesses. The ratio of debt to business profits looks even more benign—largely unchanged since the early 1980s, abstracting from recessions when profits are hammered.

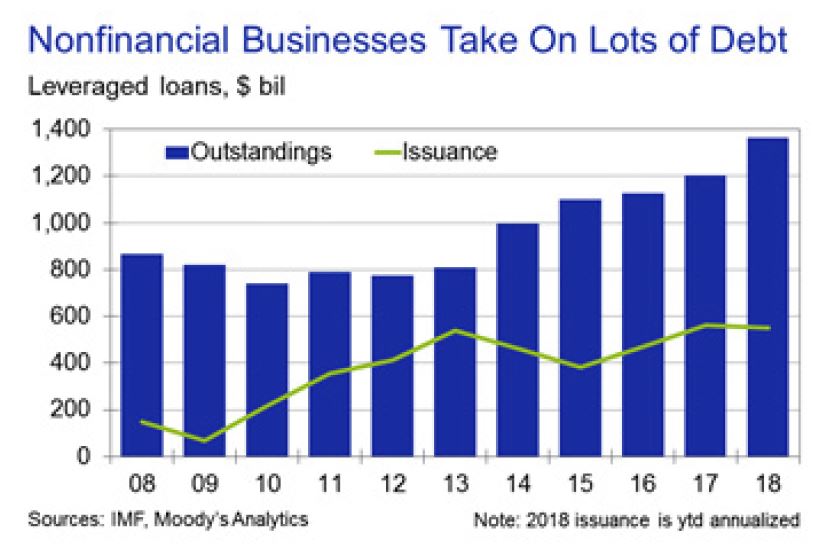

However, while businesses appear to be in good shape in aggregate, a significant number of highly leveraged companies are taking on sizable amounts of debt. This is evident in the rapid growth of socalled leveraged loans—loans extended to companies that already have considerable debt. These loans tend to have floating rates—typically Libor plus a spread—with a below-investment-grade (Baa or less) rating.

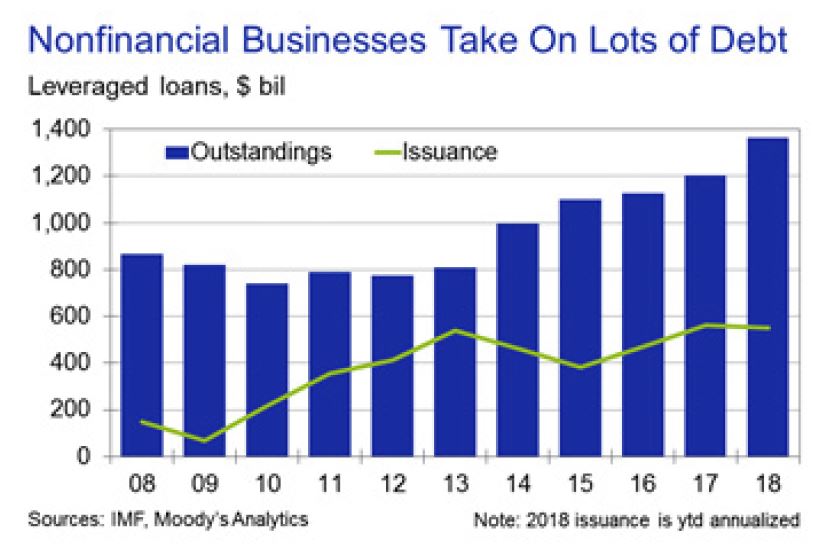

Leveraged loan volumes are setting records, and loans outstanding have increased at a double-digit pace over the past five years to nearly $1.4 trillion. Businesses use the loans to finance mergers, acquisitions and leveraged buyouts, followed by refinancing, and to pay for dividends, share repurchases and general expenses.

Powering leveraged lending is demand from the collateralized loan obligation market. CLOs are leveraged loans that have been securitized, and global investors can’t seem to get enough of them. This is clear from the thin spreads between CLO yields and comparable risk-free Treasuries.

Approximately one-half of leveraged loans currently being originated are packaged into CLOs, with CLO outstandings approaching $550 billion.

Easing underwriting

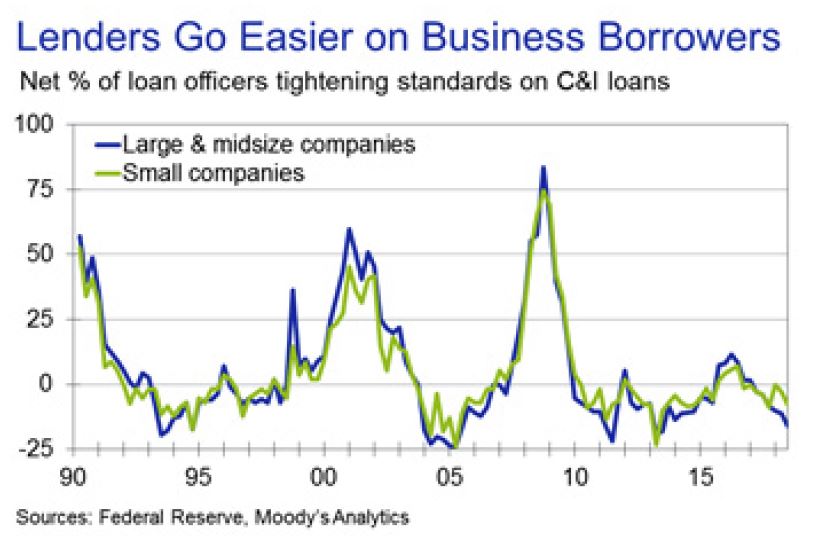

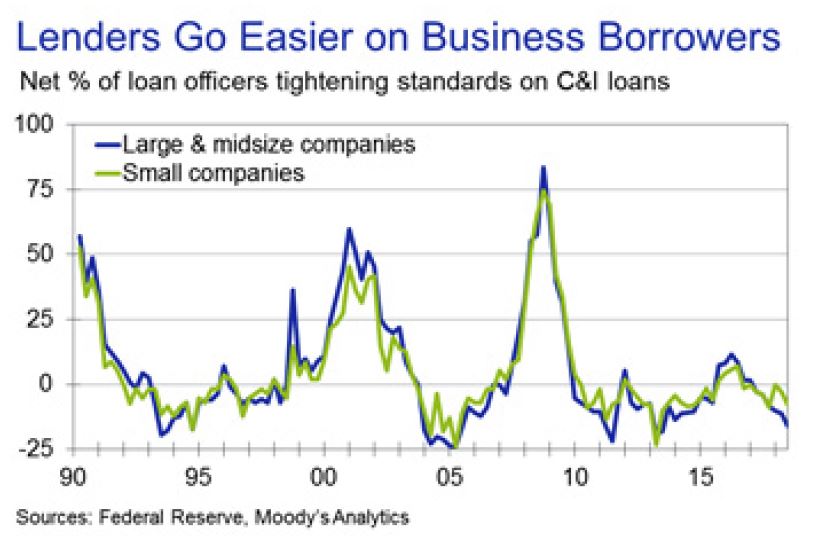

To meet the strong demand for leveraged loans from the CLO market, lenders are easing their underwriting standards. According to the Federal Reserve’s survey of senior loan officers at commercial banks, a net 15% of respondents say they lowered their standards on commercial and industrial loans to large and medium-size companies this quarter compared with the previous quarter. The only other time loan officers eased as aggressively on a consistent basis was at the height of the euphoria leading up the financial crisis in the mid-2000s. Standards for loans to small companies have not eased nearly as much, since they are much less likely to be bundled into a CLO.

Covenants on leveraged loans—restrictions on borrowers to ensure they can repay their loans—have also deteriorated, according to Moody’s Investors Service. The rating agency’s loan covenant quality indicator has fallen to its lowest level in its six-year history. Borrowers are negotiating greater flexibility to manage their balance sheets by moving or selling collateral, and they are increasingly able to sell collateral without using the proceeds to pay down their loans. It is becoming more unclear whether the collateral backstopping loans will be available in a bankruptcy.

The easing in underwriting is also evident in the below-investment-grade or junk corporate bond market.

The junk market hasn’t kept pace with the surging leveraged loan market, but it is nearly as big, with more than $1.3 trillion in outstandings. Here as well, bond covenants have eroded substantially in recent years, according to the rating agency, with the Moody’s bond covenant quality indicator currently hovering near record lows.

Eerie similarities

Considering the leveraged loan and junk corporate bond market together, highly indebted nonfinancial companies owe about $2.7 trillion. Their debts have been accumulating quickly as creditors have significantly eased underwriting standards. As interest rates rise, so too will financial pressure on these borrowers. Despite all this, global investors appear sanguine, as credit spreads in the CLO and junk corporate bond market are narrow by any historical standard.

Regulators are undoubtedly nervous—they issued guidance to banks to rein in their leveraged lending in 2013—but an increasing amount of the most aggressive lending is being done by private equity, mezzanine debt, and other institutions outside the banking system and regulators’ purview.

Now consider that subprime mortgage debt outstanding was close to $3 trillion at its peak prior to the financial crisis. Insatiable demand by global investors for residential mortgage securities drove the demand for subprime mortgages, inducing lenders to steadily lower their underwriting standards.

Subprime loans were adjustable rate, which became a problem in a rising rate environment as borrowers didn’t have the wherewithal to make their growing mortgage payments. Regulators were slow to respond, in part because they didn’t have jurisdiction over the more egregious players.

It is much too early to conclude that nonfinancial businesses will end the current cycle in the way subprime mortgage borrowers did the previous one. Even so, while there are significant differences between leveraged lending and subprime mortgage lending, the similarities are eerie.