We recently posted Out and About in Wollongong featuring the Jolly Swagman, in which we examined the state of the local economy. The show was supported by some excellent research from Mitchell Grande, a recent Graduate of Politics, Philosophy, Economics (Honours) at the University of Wollongong – concerned with Australian public policy, and especially energy policy. Today we provide additional context from his research.

His research involved three interviews across different professions, renamed for anonymity: Interviewee A, a former Development Assessment Officer in Wollongong for many years; Interviewee B, a non-governmental organisation Project Officer operating within Crown St Mall; and Interviewee C, an Economic Development Officer with the Council.

Behind these interviews is the background story of Wollongong after the turn of the century. Pioneered by rezoning of Wollongong’s inner-city industrial land, in favour of mixed-use residential developments or shop-top housing, there has been a profound shift in the local economic and labour market landscapes. Noticeably from our video, there is a lot of development reinforced by lots of Council strategies. In times like these, it’s worth getting on to the street to see behind the data and progress – and what we found was interesting: things are bad, but things are better.

Interviewee A spoke of the 2009 changes in the Local Environmental Plans (LEPs), which swung heavily toward shop-top development, including the removal of height restrictions to quite unreal limits. In their time, they approved four 10 to 30+ storey buildings in Wollongong Central Business District (CBD), and particularly around Wollongong Station – but few if any have come to fruition, due to the global financial crisis and also the poor planning-related features of ‘the Dead Zone.’ As we saw, this area had confusing commercial mixes like pawn shops and money stores, services and real estate agencies, as well as a mix of poor parking and daggy takeaways. Being the main in/out ramp of the station, foot traffic isn’t an issue – it’s just all heading somewhere else.

The 2009 LEP changes led to a major imbalance for local development, focusing on maximising residential construction and returns. Most of all, the LEP held a “very confusing and convoluted floor space ratio (FSR)” which favours commercial space but “which ‘Gong developers shy away from.” Interviewee A, here, spoke to the uniformity of FSR as a state-wide number given by the Department of Planning. This, not rates, is one major reason for vacancies. These kind of planning controls have steered local cities into densification, gentrification, and an expanding zone of unaffordability through urban sprawl, visualised by ghost shops.

After walking a few blocks toward the mall, noticeable changes in both vibrancy and vacancy were apparent. More services, notably health and wellbeing, as well as massage parlours and more cheap loans shops (for every one of those there was a couple more vacancies). A diverse street, for sure. But whether these are real drivers of economic growth, value creation, or just inelastic goods and services is implicit. Among all else, this type of job mix reinforces underemployment and poor wage conditions for the city.

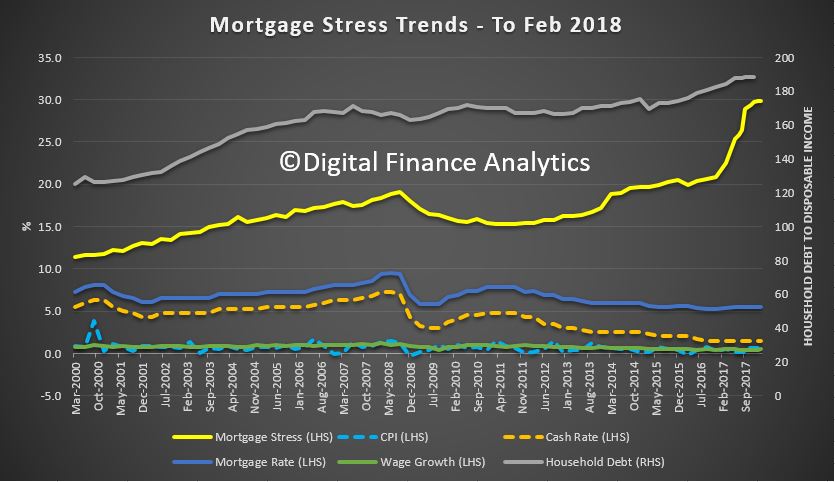

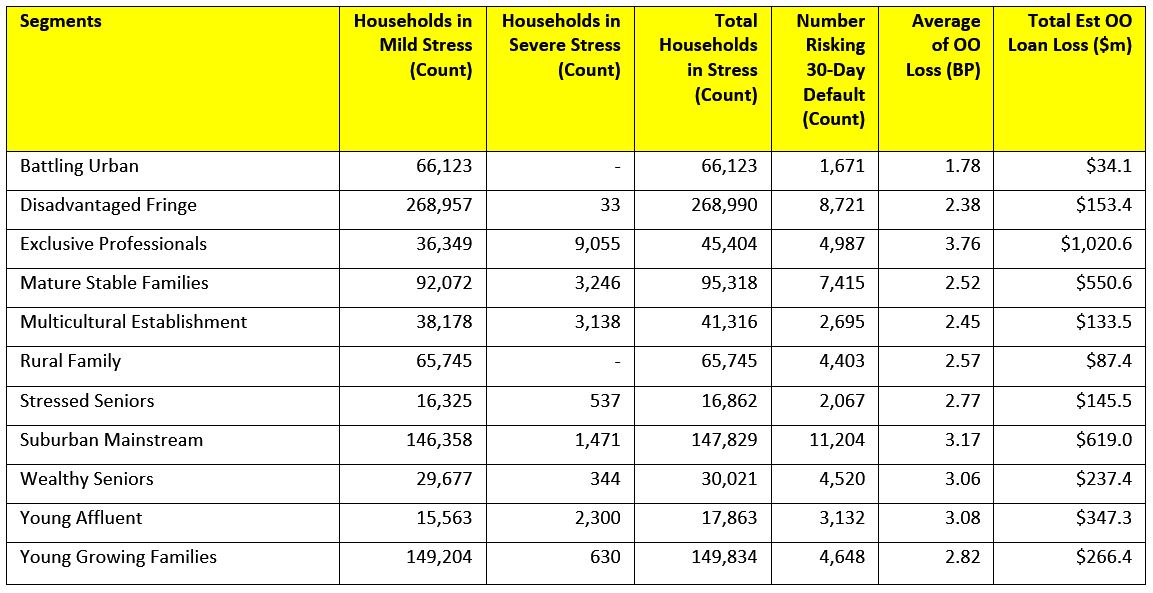

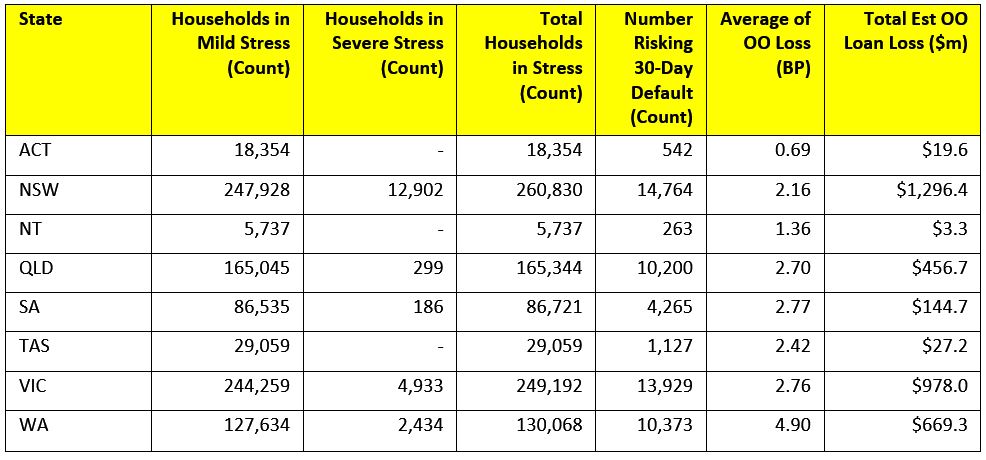

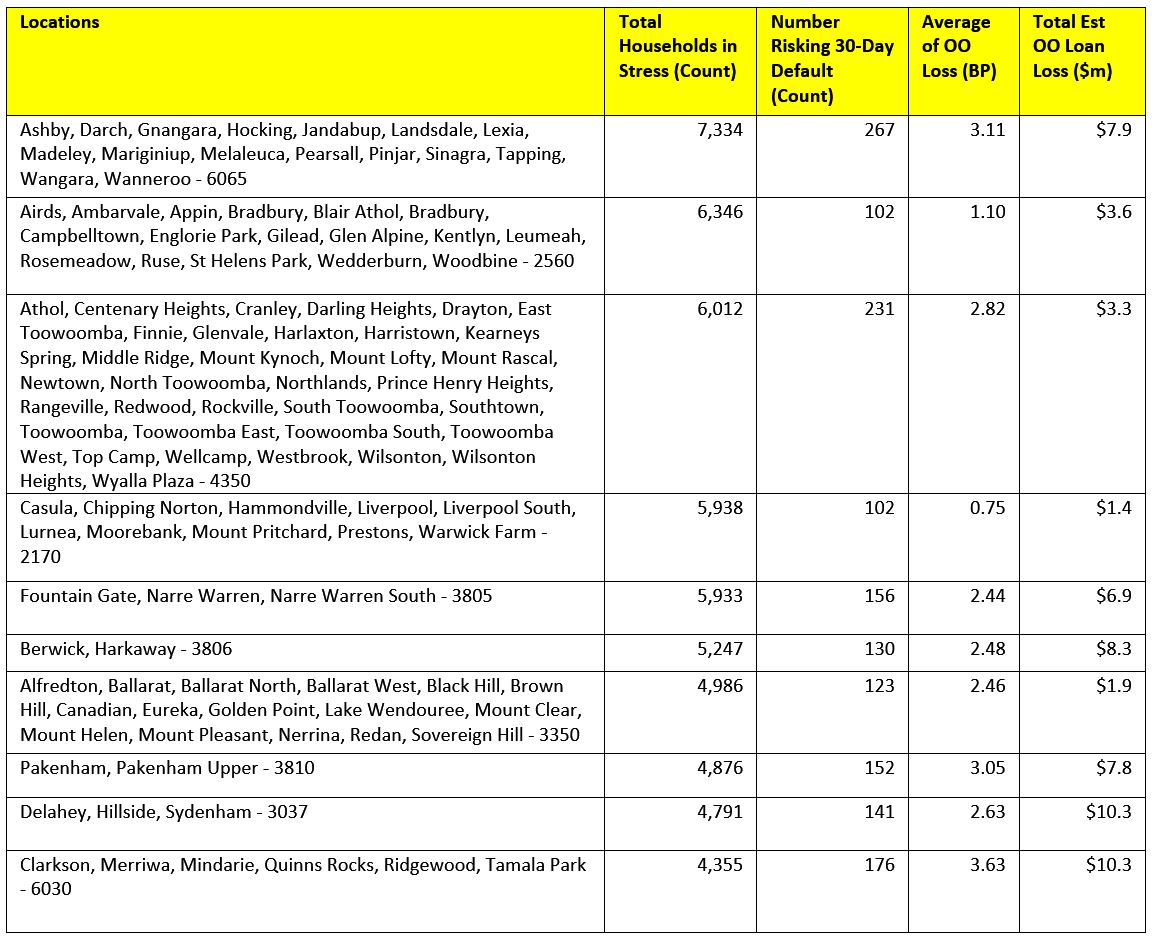

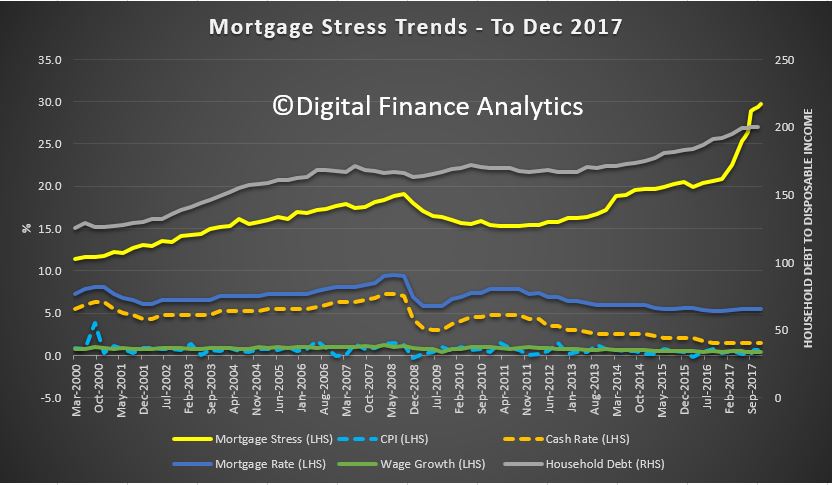

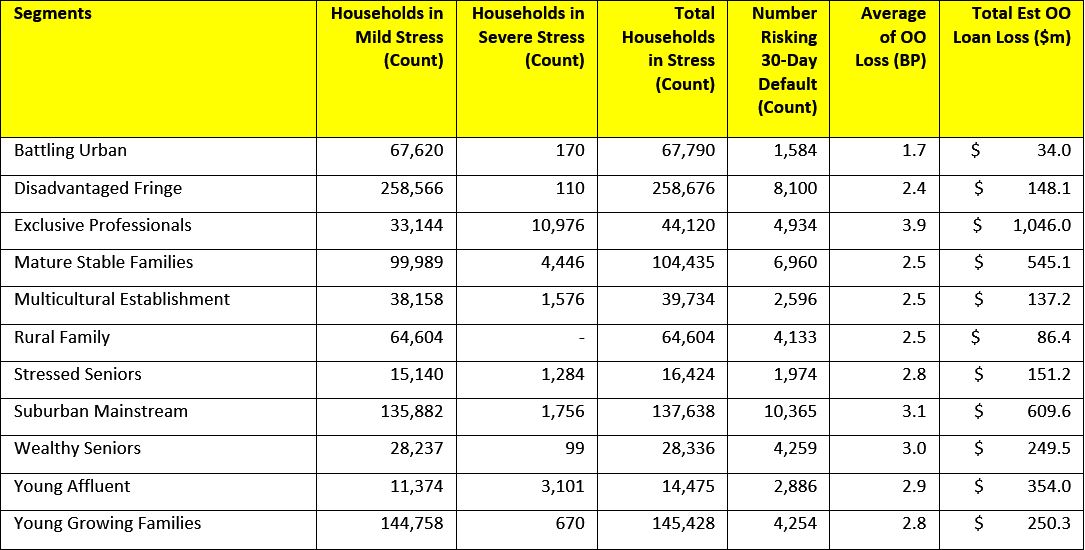

The area between the Mall and the Dead Zone is hindered by the de-integration between these areas and the Hospital, having little draw in value and liveliness. As well, high running costs, high rents, low retail spending, and rising mortgage stress… these businesses would be betting heavily on new demand from the towers being built behind it. The story of de-integration between these areas is synonymous with the entire Wollongong local government area – albeit a much larger story – disjointed between education, health, metro, and recreation precincts.

For Interviewee B, the new retail segment of Crown St Mall has been chancy. It serves its purpose as a hub for, say, going to Chemist Warehouse or JB Hi-Fi, as well as having a food court and strip of restaurants – where most, if not all, are either chains, franchises, or commonplace brand names. This section has dramatically shifted the CBD’s centre of gravity, with rare if any vacancies appealing to consumers. Foot traffic is strictly to the centre (or the Mall), with people passing by proximate eateries, bus stops, and many vacancies – whether these feet notice and buy from these surrounds is another question. Interviewee B spoke to the ability of chains and big box retailers to withstand higher rents and ‘cyclical’ lower sales than, say, the local butcher who stuck it tough across from Coles.

Following a pitstop at Wollongong’s big box centre, we finally ventured down Crown St Mall. A perfect Spring day in the ‘Gong, with a foragers market spanning a third of the way. For a midday Friday, it was plenty bustling. But the ground floor and upstairs vacancies were pervasive, with one for sale or for lease every few stores. In particular, the diversity of the store fronts was fairly constrained to health services, global brands, banks and financial services, as well as the tried and true café/bar.

Interviewee B works in the space between government and landlords, seeking to fill Crown St Mall vacancies with ‘makers and creators’ until the landlord finds a apposite tenant. These makers and creators run on a continually renewing 30-day license, while the shopfront is still advertised as for lease. Although not very well showcased in the video, these spaces are filled with new ideas and tenants who are battling through the local economic shift from traditional retail models. For these tenants, rents remain high as much as turnover remains low: a recent fix of already poor consumption hampered by online shopping and buy-now-pay-later services. In short, it is important to keep the Mall vibrant with non-traditional stores but “no way can [makers and creators] step into Crown St Mall on a full rental lease…” averaging $1,500 per week.

This form of short-term leasing is, in my opinion, successful insofar as it allows business who would otherwise shift into the ‘burbs a chance at establishing customers and proficiency in a pedestrian mall setting. It has successfully brought vibrancy to otherwise dingy spots of the Mall, like Globe Lane; an impressive growth story. The main question, in the long run, is the scheme’s sustainability and whether it can positively impact wages or the local economy through a surge in value added or productive activities. A very tall order.

Toward the end of the pedestrian Mall, where the market had ceased, we stopped again. The pattern of financial services and vacancies continued. Beyond the Mall toward the beach, although not featured in the video, is an interesting few blocks of many independent takeaway joints (bars, cafes, burgers), public administration buildings, and spats of development. Of note, lots of recently built shop-top housing is sparingly filled with ground floor tenants and is adjacent to more under construction mixed-use buildings.

As spoken to in the outset, the LEP rezoning of the inner-city toward the mixed-use development model has severely jolted the labour market, favouring both services and residential construction over value-added or manufacturing businesses. The inner-city land which surrounds the mall once retained over 12,000 manufacturing jobs back in 2007-2008. Since, the sector has fallen to 6,000 employees (2017-2018). Importantly, this is a treble effect of rezoning pressuring SMEs out of the inner-city, as much as it is higher rents and growing specialisation of overseas low-wage competitors grounding out businesses.

Interviewee B has seen this all too often, especially along Crown St Mall. SMEs are highly leveraged in personal debt and burdened by cost of living pressures, reluctant to fully close and instead stay fraught with affordability. Because of this, in their experience, tried ideas leave but rarely relocate. And if they were to, it would be out of the inner-city over to Fairy Meadow or Corrimal.

Interviewee C was well aware of the loss of manufacturing jobs, reiterating the Council’s commitment to public and private investment into office space, framing the opportunity to tap into the services labour market. Equally, investment is being directed to ‘[meet] the demand of inner-city living’ with shop-top housing increasing by 1,500 dwellings over 2016-2021. But glaringly, “the profitability and investment return of residential development has far outweighed the commercial management of development, leaving very little room for management.” It is intended that current and future investment will positively serve the anchor tenants, which, on the one hand, should be true as long as local population grows, and sustainable businesses land a lease. Easily done, right? But as we know, the ever-present question of demand and the ability to match is very uncertain.

Interviewee A believes the transition from manufacturing (etc.) will continue ever onward toward a service-based economy. Through such, they foresee more sociocultural flight, more commercial shortfalls in transition, and more finance being tied into housing, rents and accommodation. To stave off the current ‘feel’ of the ‘Gong, they suggest, “either someone at UOW needs to create the next Google” or locals must have all their needs localised and accommodated, meaning minimal commute times for work or health related specialists.

Which brings us to Lang’s Corner, set to be a 10-or-so storey commercial office tower at the so-called end of the Mall. Interviewee C strongly affirmed the need for high-quality office space as a main driver of jobs growth. This goes with councils target of 1,050 jobs per annum until 2030, by retaining local skills and accommodating those shifting from Uni or primary industry, to become a ‘nationally significant city.’ Lang’s Corner is a part of “30,000 sqm of new commercial space, including 16,500 sqm of A-grade office space…” in the pipeline. Interviewee C then shared a number of reports which reaffirmed their position about the economic health and needs of Wollongong:

- Knight Frank’s 2017 report said that Wollongong’s “A-Grade office vacancy rate currently measures 8.5% (from 74,626 sqm total A-Grade stock) …” citing that “vacancy will reduce significantly in early 2017 following the recent announcement that the SES will move to the former ATO building.”

- And then in their 2018 report that “[at] 10.6%, Wollongong’s office vacancy rate is currently at its lowest level in five years, having declined from 11.2% in January 2017…” and that “Limited leasing options are causing rents to rise…” “…prompting the need for more office space in Wollongong to facilitate economic development.”

- The 2019 Office Market Report, published by the Property Council of Australia, found that there is currently a shortage of office space in the city centre – a much smaller zone than Knight Frank’s. Here, “the vacancy rate for A-grade is low at just 1.4%.”

- It was in that report that “Total vacancy decreased from 10.6 percent to 10.0 percent in the year to January 2019; The vacancy decrease was due to 2,518sqm of withdrawals; and Demand was negative with -1,387sqm of net absorption recorded”

- A Herron Todd White report found commercial vacancies “flat”, however, held optimism going into 2020 due to a ‘recovering housing market’ and interest rate cuts which ‘should stimulate retail spending’.

- This report also profiled Wollongong as having “Leasing conditions [which] have continued a long term trend of being static given above average vacancy rates and generally soft demand, while supply continues to be introduced to the market given the large number of mixed-use projects completed in the Wollongong CBD over recent times and with additional projects also being developed at present…”

- But importantly “There is no upward pressure being placed on rental rates with conditions generally favouring tenants.” They claimed that buyer demand does exist, however, had not shone through in 2019.

Interviewee A rejects the need for more office space, rather “there is a good mix… it [demand] is just not really there.” As well, “the vibrancy and feel of the place [in comparison to, say, the Shire CBDs along the trainline] also isn’t there…” “it has its own feel.” Interviewee A then went on to warn that current population and consumer issues, as well as demand and ability issues, will maintain the commercial sprawl and only increase vacancies and intimidate overindebted SMEs.

It appears that the real surge behind this demand/shortage of office space/scarce supply-induced rents is largely due to the residential development imbalance, in that Council has been ‘all in’ on housing speculation for some time, now requiring mammoth investments into commercial/office space. The frankly obtuse ratio of residential to commercial floor space has reduced local labour market diversity (i.e. losing manufacturing and primary industry, gaining services and food) in opting for shop-top developments. It is now vital, for the sustainability of the region, to catch up.

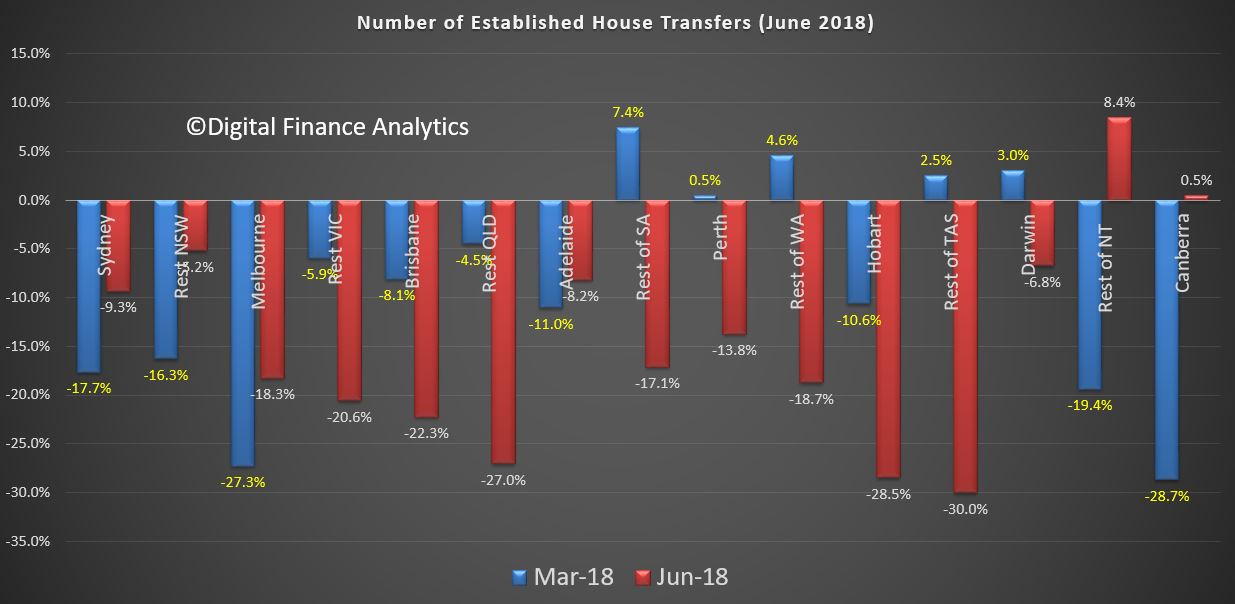

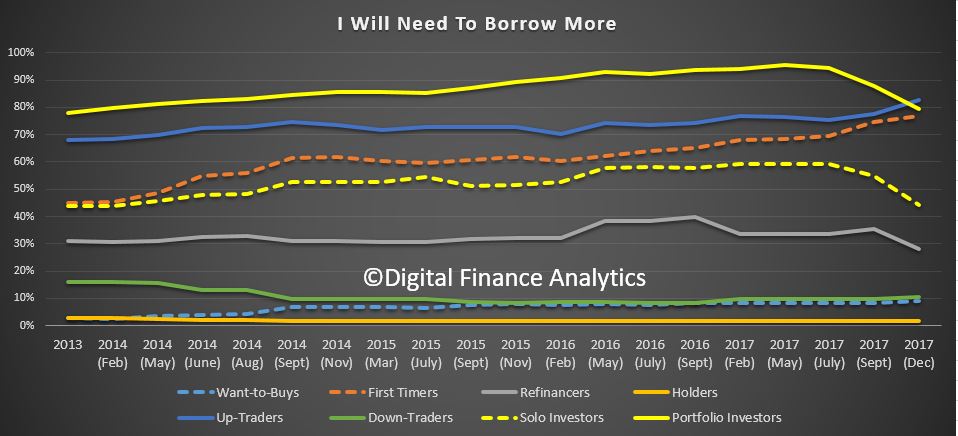

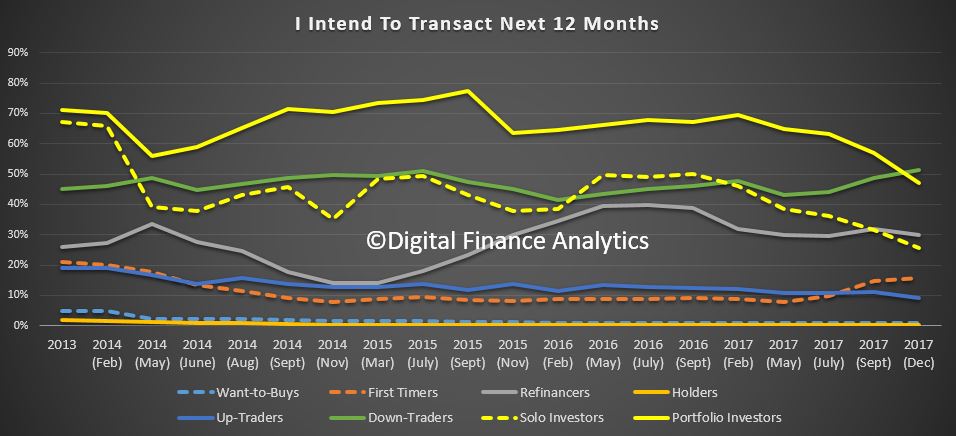

At the close of the video, we stood beneath two new mixed-use towers of 22 storeys and 19 storeys, with another under construction down the road set to be 21 storeys. The main questions which stuck with Joe and Martin were how the ‘Gong would absorb this supply, especially given population growth of 0.8% and the current macroeconomic conditions. Given the trend in local rents and consumer spending, will the ground floors be leased? Because, as we have seen play out across Australia’s junior CBDs, vacancies in newly constructed mixed-use buildings have been ubiquitous, with high turnover of retailers going bust or relocating out of mixed-use buildings, just to be replaced by ‘essential’ services. It is locally apparent that landlords refuse to lower rents for non-service tenants, in order to protect their loan-to-value ratios and avoid bank repayments.

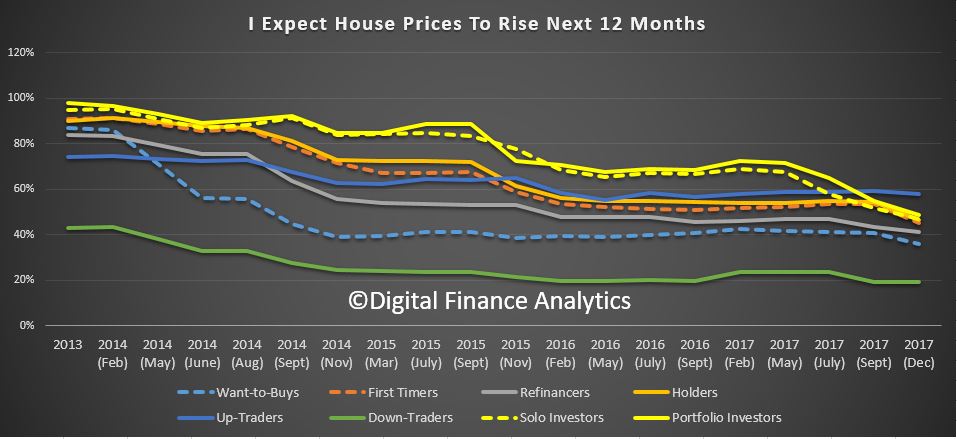

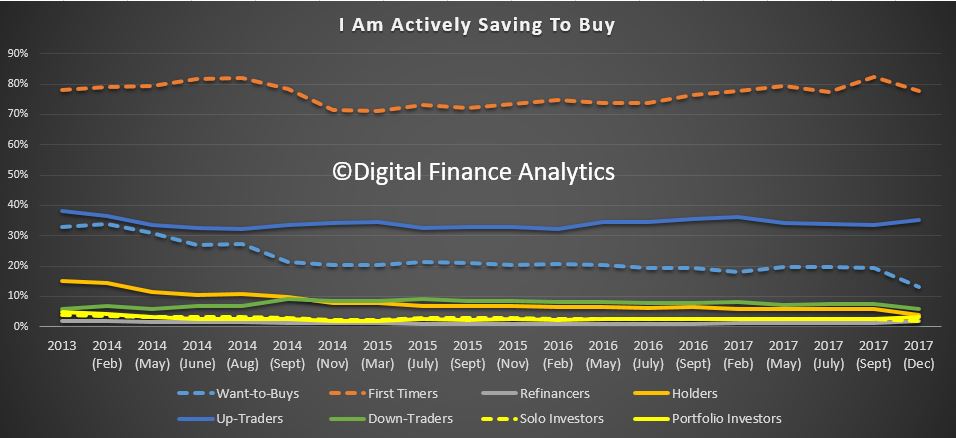

It’s especially uncertain whether such an increase in residential supply will depress local prices, maintain the 2018 highs to maximise developers’ return, or be taken by domestic market, supposedly, upward. Council is fairly certain on developing more sooner, stylised by a great deal of high-rise development. At present, Wollongong has over 18 cranes: 8 were mixed-use residential (Parq on Flinders, Crownview Wollongong, Signature in Regent St, Avante in Rawson St, Skye Wollongong, Atchison St, and the Verge in Underwood St, Corrimal); 5 were residential (Loftus, Beatson and Church streets, The Village in Corrimal); 3 were commercial (Getaway, IMB Banks, Lang’s Corner); 2 at the University of Wollongong, and 1 day surgery at Urunga Parade. Local construction is at a high – only being beaten by Gold Coast with 29 cranes and Adelaide with 19 cranes on the infamous Crane Index.

Given the palpable feel of vacancies on the ground around these development cites, it seems that the area might soon be flooded with mixed-use and commercial space at a highly inopportune time in the market. It’s hard to tell whether the ground-level retail/commercial spaces of these under construction towers can actually be filled – let alone sustained – by their anchor tenants, or whether diverse business ideas (other than services or cafes) can be sustained. Again, this is a treble effect of local consumers preferring the brand name hard-top retailers, as well as online shopping and buy-now pay-later services, which eat away at the turnover needed to sustain the sticky high rents.

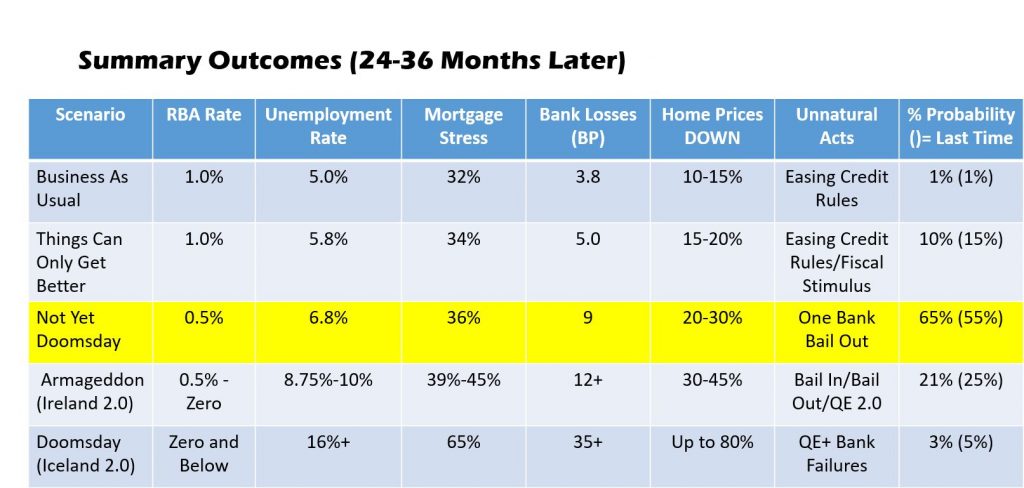

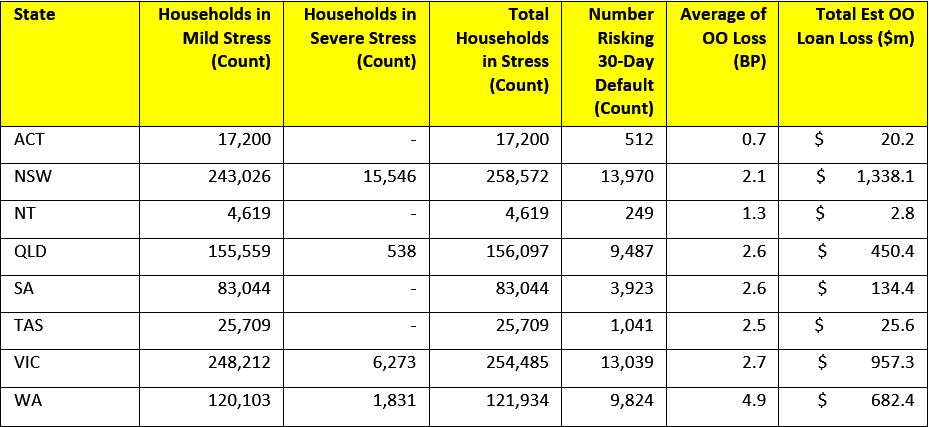

It seems we can only wait and see what will amount of the ‘Gong’s residential and commercial mix. Of course, the current lived reality in the local economy – slow income growth, high debt and mortgage stress, wobbly house prices, as well as a retail recession, high rents, and collapsed construction approvals – seems to imply one story, experience across Australia. While optimistic advocates of the ‘build it and they will come’ mantra seem to be telling us another.